APA Style

Sheerin Masroor, Ajay Kumar, Archana Goswami, Hari Krishan, Saddam Hussain, Mohammad Ehtisham Khan. (2025). Sustainable Approaches Towards Nanomaterial Synthesis: Strategies, Properties, and Process Integration. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0011). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.162533MLA Style

Sheerin Masroor, Ajay Kumar, Archana Goswami, Hari Krishan, Saddam Hussain, Mohammad Ehtisham Khan. "Sustainable Approaches Towards Nanomaterial Synthesis: Strategies, Properties, and Process Integration". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0011, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.162533.Chicago Style

Sheerin Masroor, Ajay Kumar, Archana Goswami, Hari Krishan, Saddam Hussain, Mohammad Ehtisham Khan. 2025. "Sustainable Approaches Towards Nanomaterial Synthesis: Strategies, Properties, and Process Integration." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0011. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.162533.

ACCESS

Review Article

ACCESS

Review Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0011

Sheerin Masroor

masroor.sheerin@gmail.com

Ajay Kumar

ajay.tiwari1591@gmail.com

Archana Goswami

agoswami@gdkr.ac.in

Hari Krishan

hkrishnan@mdlc.us.in

Saddam Hussain

shussain@patiputrau.ac.in

Mohammad Ehtisham Khan

mekhan@jazanu.edu.sa

1 Department of Chemistry, A N College, Patliputra University, Patna 800013, Bihar, India

2 Department of Chemistry, School of Applied and Life Sciences, Uttaranchal Institute of Technology, Uttaranchal University, Dehradun 248007, Uttarakhand, India

3 Department of Biochemistry, Giri Diagnostic Kits and Reagents Pvt. Ltd., Selaqui, Dehradun-248011, Uttarakhand, India

4 Department of Chemistry, Michigan Diagnostic LLC, 2611 Parmenter Blvd, Royal Oak, MI 48073, USA

5 Department of Chemical Engineering Technology, College of Applied Industrial Technology, Jazan University, Jazan 45142, Saudi Arabia

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 18 May 2025 Accepted: 20 Aug 2025 Available Online: 21 Aug 2025 Published: 02 Sep 2025

Nanomaterials (NMs) are a unique class of materials with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nm, exhibiting exceptional properties distinct from their bulk counterparts. Their high surface area, as well as tunable physical, chemical, and magnetic behaviors make them valuable across diverse applications. Phase transitions, such as the emergence of magnetism at the nanoscale, highlight their distinctiveness. This review outlines the historical development of NMs and clarifies key terminology. It covers major synthesis techniques, including top-down and bottom-up approaches, and highlights the unique features that define nanoscale matter. A comprehensive overview of various NMs, such as fullerenes, graphene, carbon nanotubes, MXenes, and core–shell nanoparticles (NPs) is presented. The paper concludes with an overview of current challenges and future directions in the field of NMs.

Overview of sustainable top-down and bottom-up nanomaterial synthesis methods. Unique size-dependent properties of nanomaterials are discussed. Covers key nanomaterials: fullerenes, graphene, CNTs, MXenes, core–shell NPs. Clarifies essential nanoscience terms and historical development. Outlines current challenges and future prospects in nanomaterial research.

The advent of nanotechnology can be traced back to the visionary lecture by Richard Feynman in 1959, titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” in which he proposed the idea of manipulating matter at the atomic level [1]. However, nanotechnology began to flourish as a formal scientific discipline in the early 1980s with the development of tools such as the scanning tunneling microscope (STM) and atomic force microscope (AFM), enabling visualization and manipulation at the nanoscale. Nanotechnology has developed rapidly over the past few decades, driven by advances in materials science, biotechnology, and engineering. It has led to revolutionary applications in energy, medicine, electronics, and environmental remediation. Research indicates that nanotechnology’s impact on science and industry will be transformative over the next few decades, as evidenced by recent literature reports [2]. The development of nanotechnology is considered one of the most important scientific achievements of the twenty-first century. The field encompasses a variety of disciplines and focuses on the synthesis, manipulation, and application of materials less than 100 nm in size. As a result, nanoparticles (NPs) have applications in biotechnology, biomedicine, food, agriculture, and environmental sciences. Specific examples include wastewater treatment[3], functional food extracts and environmental monitoring [4], and antimicrobials [5]. Nanoparticles are biocompatible, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and exhibit efficient drug delivery, bioactivity, tumor targeting, enhanced bioavailability, and improved biosorption. These properties make them increasingly useful in biotechnology and applied microbiology. Ultrafine particles or NPs describe a particle of matter with a diameter of one to one hundred nanometers (nm). Due to their small size and large surface area, NPs often display unique size-dependent characteristics [6]. When a particle approaches or falls below the de Broglie wavelength or the wavelength of light, its characteristic length scale disappears, disrupting the crystalline particle’s periodic boundary conditions [7]. As a result, many unique applications of NPs arise from their physical properties differing significantly from those of bulk materials[8]. Since the beginning of this century, nanomaterials have become increasingly crucial to scientific and technological progress. For instance, addressing global warming and climate change requires the use of green technologies, many of which rely on NMs. The effectiveness of NP-based technology is greater than that of bulk materials [9,10]. Furthermore, NMs are being used to develop diagnostic, treatment, and prevention techniques for various global disease epidemics sweeping the globe. For instance, in 2019, NPs were used to identify and treat COVID-19, a disease that caused widespread mortality worldwide. Furthermore, the identification and treatment of the monkeypox pandemic that is currently sweeping worldwide were made possible by the use of NMs [11,12,13]. It is anticipated that nanotechnology, nanoscience, and NMs will be crucial to global development in the future. Consequently, the scientific community and society need to possess sufficient information and comprehension of NPs.

NMs are commonly classified based on their dimensionality, which significantly influences their physical, chemical, and functional properties. This dimension-based classification divides NMs into four categories: zero-dimensional (0D), one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) structures. In 0D NMs, all three dimensions are confined within the nanoscale (1–100 nm). Examples include quantum dots and NPs, which exhibit quantum confinement effects, resulting in unique optical and electronic properties ideal for imaging, biosensing, and optoelectronics [14]. 1D NMs, such as nanorods, nanowires, and nanotubes, have one dimension outside the nanoscale range. The high aspect ratio of their surfaces and the ability to transport electrons make them an attractive material for nanoelectronics, solar cells, and drug delivery. The extraordinary mechanical strength of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), combined with their electrical conductivity, makes them ideal for flexible electronics and composite structural materials [9]. In the case of nanomaterials with two dimensions, such as graphene and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), only one dimension is at the nanoscale (thickness), while the other two dimensions (length and width) are at the macroscale. These materials possess a significant surface area and exhibit both electrical conductivity and mechanical flexibility. In addition to serving as excellent electrocatalysts and energy storage materials, they are also highly effective sensor materials. A three-dimensional nanostructure comprises of nanoscale building blocks arranged in a bulk manner within the structure. This category includes nanocomposite materials, dendrimers, and foams with nanostructured features. Nanoscale features are present in their internal structure, even though they are not fully contained within the nanoscale. They are widely used as biomedical implants, environmental remediation materials, and structural materials. Across diverse industries, including electronics, medicine, and environmental engineering, dimension-based classification provides guidance in selecting materials for specific applications based on shape and size. The NMs dimension-based classification is provided in Figure 1. Over the past two decades, a great deal of research has been conducted on nanomaterials and NPs [9]. Numerous recent studies, however, seem to concentrate on the characteristics, methods of preparation, applications, and classification of each NM [16,17,18,19,20]. Currently, there is no comprehensive research detailing the properties, preparation, and classification of NMs applicable across all disciplines. A comprehensive examination of each NM category, including the rationale behind its classification and preparation, is necessary to address this gap. These materials are relevant to all classes, properties, and application sectors.![Figure 1: Dimensional classification of the Nanomaterials (NMs) [15].](/uploads/source/articles/sustainable-processes-connect/2025/volume1/20250011/image001.png)

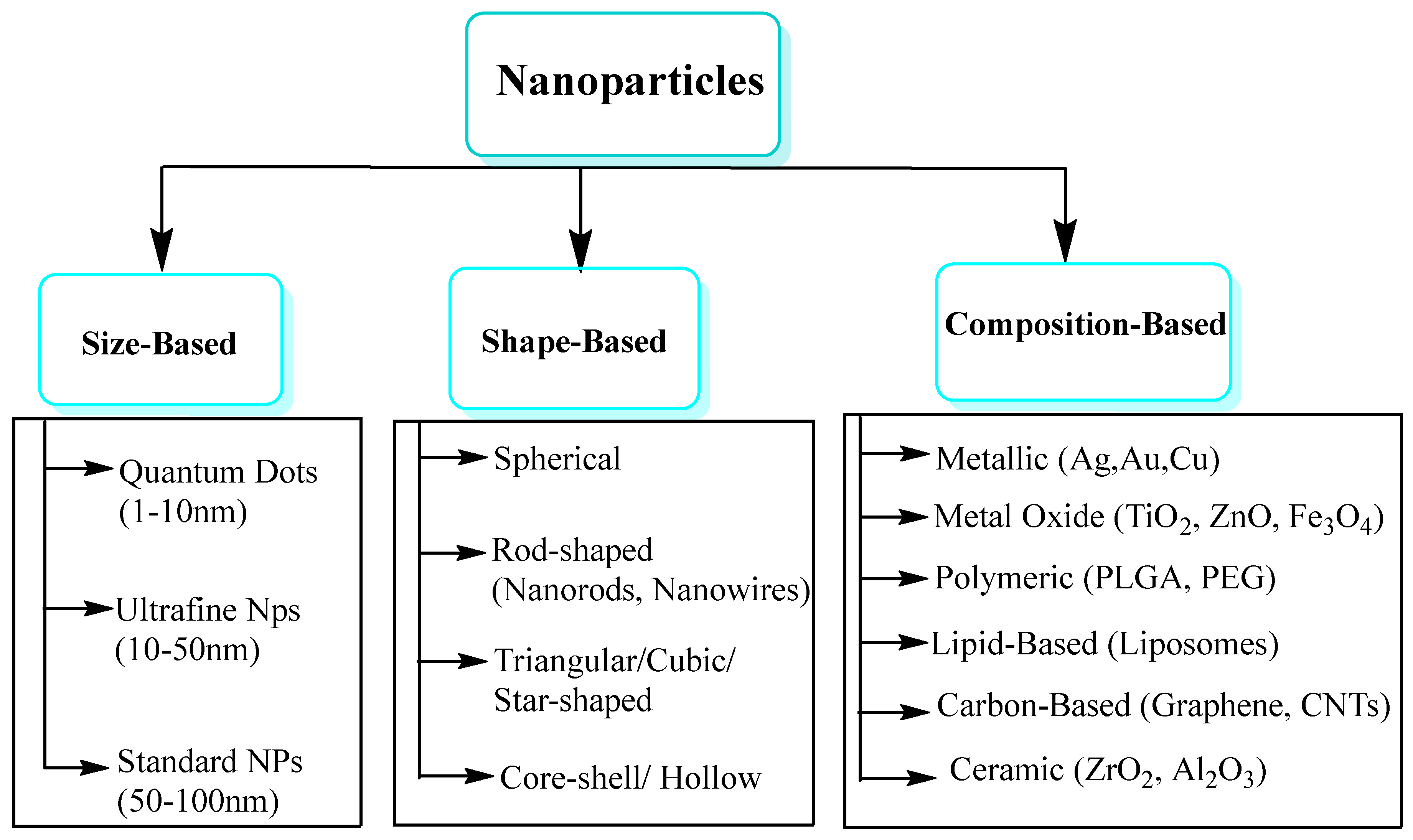

NPs are generally categorized based on three primary criteria: size, shape, and chemical composition. The remarkable mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), along with their electrical conductivity, make them ideal for flexible electronics and structural composites[8,21]. Nanomaterials with two dimensions, such as graphene and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), have only one dimension at the nanoscale (thickness), while the other two dimensions (length and width) are at the macroscale. Owing to their large surface area, electrical conductivity, and mechanical flexibility, these materials serve as excellent electrocatalysts, energy storage devices, and sensors. Bulk nanoscale building blocks assemble in three dimensions to form three-dimensional structures. This category comprises nanocomposites, dendrimers, and nanostructured foams. Although not all features are at the nanoscale, nanoscale characteristics can still be identified within their internal structures. Their applications include biomedical implants and environmental remediation materials. According to dimension-based classification, dimensions determine the material best suited to specific applications across a range of industries, including electronics, medicine, and environmental engineering [22,23] see Figure 2. A comprehensive and integrative review of NMs is provided in this article. As a result, it provides a comprehensive overview of their development, fundamental concepts, synthesis strategies, and unique physicochemical properties. Unlike previous reviews that focused on specific NMs or techniques, this work examines a wide range of NMs, including fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, graphene, MXenes, core–shell structures, and emerging 2D materials, highlighting their unique nanoscale properties. There are several features of this review that make it unique, including an extensive classification of synthesis methods, a comparative discussion of recent advances, and the inclusion of underrepresented materials. It provides researchers across the fields of materials science, nanotechnology, and interdisciplinary applications with valuable insights.

A convergence of experimental developments in the 1980s, including the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope in 1981 and the discovery of fullerenes in 1985, led to the advancement of nanotechnology. In 1986, the book Engines of Creation presented a framework for nanotechnology’s goals [24].

During the third millennium BC, Keladi pottery dated between 600 and 300 BC was found to contain carbon nanotubes [25]. It has been discovered that cementite nanowires have been present in Damascus steel from around 900 AD; however, their origin and method of manufacture remain unknown. Additionally, it is unknown how they originated or whether their presence in these materials was intentional.

In the next decade, metal alloy nanoparticles, such as silver-copper (Ag-Cu) and platinum-cobalt (Pt-Co), will be increasingly developed for multifunctional applications across a wide range of scientific fields and industries. In applications such as photonic devices, antimicrobial agents, and sensors, these alloyed nanostructures integrate the unique characteristics of different metals. Chemical and biological sensors are highly sensitive and selective due to their distinct structural and electrical properties. Alloyed metals exhibit extensive antimicrobial properties resulting from their synergistic interactions, proving effective against resistant bacteria. In photonics, the unique optical properties of metal NPs can be exploited for advanced light manipulation in imaging and optical communication systems [26,27]. Over the past decade, considerable attention has been given to the enhanced performance of bimetallic nanoparticles, including silver–gold (Ag–Au) and palladium–gold (Pd–Au). Bimetallic nanoparticles, compared to monometallic nanoparticles, exhibit greater catalytic activity and improved spectral behavior. Furthermore, the interaction between the two metals improves electronic properties, surface reactivity, and stability. These materials have various applications, including chemical catalysis, environmental remediation, and biosensing. In addition, their adjustable optical characteristics, such as surface plasmon resonance, have led to a wide range of imaging and diagnostic applications [28,29]. Significant advancements have also been made in the field of metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles, including Fe3O4 (magnetite), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni). A broad range of biomedical applications can be achieved with nanomaterials due to their magnetic and biocompatible properties. As contrast agents, they improve the clarity and accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially in clinical applications. Their responsiveness to external electromagnetic fields enables their use in targeted drug delivery. The therapeutic agents were then transported precisely to their targets within the body. As a further benefit, their use in electromagnetic hyperthermia provides a promising method for treating cancer by rapidly destroying tumor cells without harming healthy tissues nearby [30,31]. A single-walled carbon nanotube with a diameter of one nanometre was produced by Iijima and Ichihashi in 1993, following the discovery of carbon nanotubes in 1991. An example of NM is carbon nanotubes, also known as Bucky tubes, which contain a hexagonal lattice of carbon atoms in two dimensions. Hollow cylindrical structures are created by rolling graphene sheets in one direction and joining their edges together. Researchers such as Chen et al. speculate that carbon nanotubes bind between graphene (two-dimensional) and fullerene (zero-dimensional) [32]. In addition, nearly 120 years ago, M. C. Lea reported making citrate-stabilized silver colloids [33,34]. Using this method, particles with an average diameter of 7 to 9 nm can be created. Recent studies have confirmed the nanoscale size and citrate stability of nano-silver synthesized using silver nitrate and citrate, the nanoscale size, and citrate stability [35]. Earlier research also showed that proteins could stabilize nanosilver as early as 1902 [36]. “Collargol” is the name of a commercially produced nanosilver that has been utilized in medicine since 1897. A particular kind of silver NPs called collargol has a particle size of roughly 10 nanometres (nm). The diameter of Collargol was found to fall within the nanoscale range, as early as 1907, measuring between 2 and 20 nm. In 1953, Moudry developed gelatin-stabilized silver NPs, representing a distinct type of silver nanoparticles. A different technique from Collargol was used to create these NPs. According to a patent, “for optimal efficiency, the silver must be disseminated as particles of colloidal size less than 25 nm in crystallite size,” which indicates that the inventors of nano-silver formulations understood the need for nanoscale silver decades ago. Originally used to stain and adorn glassware throughout the Roman Empire, gold NPs have a lengthy history in chemistry. A century ago, Michael Faraday may have been the first person to notice that colloidal gold solutions were different from bulk gold. In 1857, Michael Faraday conducted research on the components and production process of colloidal suspensions of “Ruby” gold. Their unique optical and electrical properties place them among the magnetic NPs. Faraday demonstrated how gold NPs might produce solutions with different hues under particular lighting conditions [37] Table 1. Illustrates milestones in the year-wise chronological discovery and application of metal NPs.

S. No.

Year

Discovered Metal NPs

Application

1.

2020s

Metal alloy NPs (e.g., Ag-Cu, Pt-Co)

Designed for multifunctional applications: sensors, antimicrobials, and photonics.

2.

2010s

Bimetallic NPs (Ag-Au, Pd-Au, etc.)

Engineered for enhanced catalytic and optical properties.

3.

2000s

Magnetic Metal Oxide NPs (Fe3O4, Co, Ni)

Widely developed for MRI, drug delivery, and hyperthermia treatment.

4.

1991

Carbon NPs / Nanotubes -Iijima

Discovery of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) using metal catalysts.

5.

1980s

Platinum (Pt) & Palladium (Pd) NPs

Used in catalysis and hydrogenation reactions; applications in fuel cells.

6.

1971

Citrate-stabilized Ag NPs- M.C. Lea

Synthesized 7–9 nm silver NPs using citrate reduction, a widely referenced method.

7.

1953

Gelatin-stabilized Ag NPs Moudry

Introduced gelatin as a stabilizing agent; developed stable nano formulations

8.

1907

Size of Collargol Defined

Determined to have a diameter between 2–20 nm, confirming nanoscale size.

9.

1902

Silver NPs with Protein Stabilizers

Use of protein to stabilize silver NPs, precursor to biomedical uses.

10.

1897

Silver (Ag) NPs Collargol

Commercial nanosilver is used as an antimicrobial agent in medicine.

11.

1857

Gold (Au) NPs- Michael Faraday

First scientific study of colloidal gold, observing color variation due to particle size.

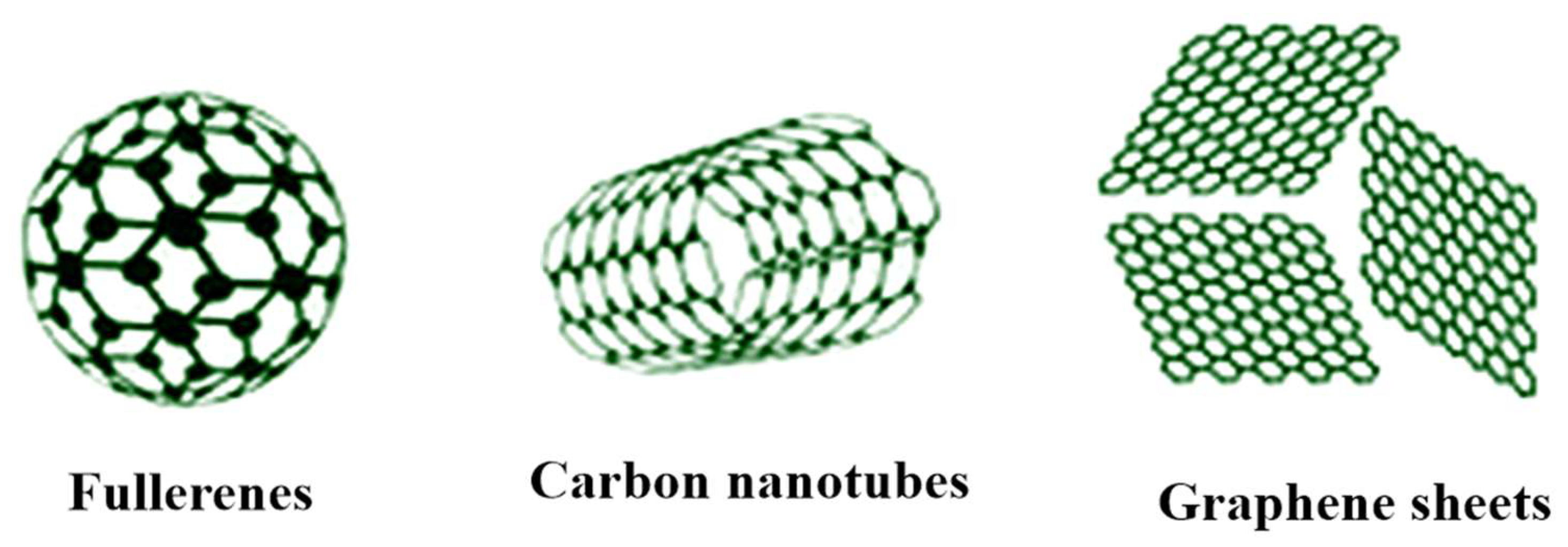

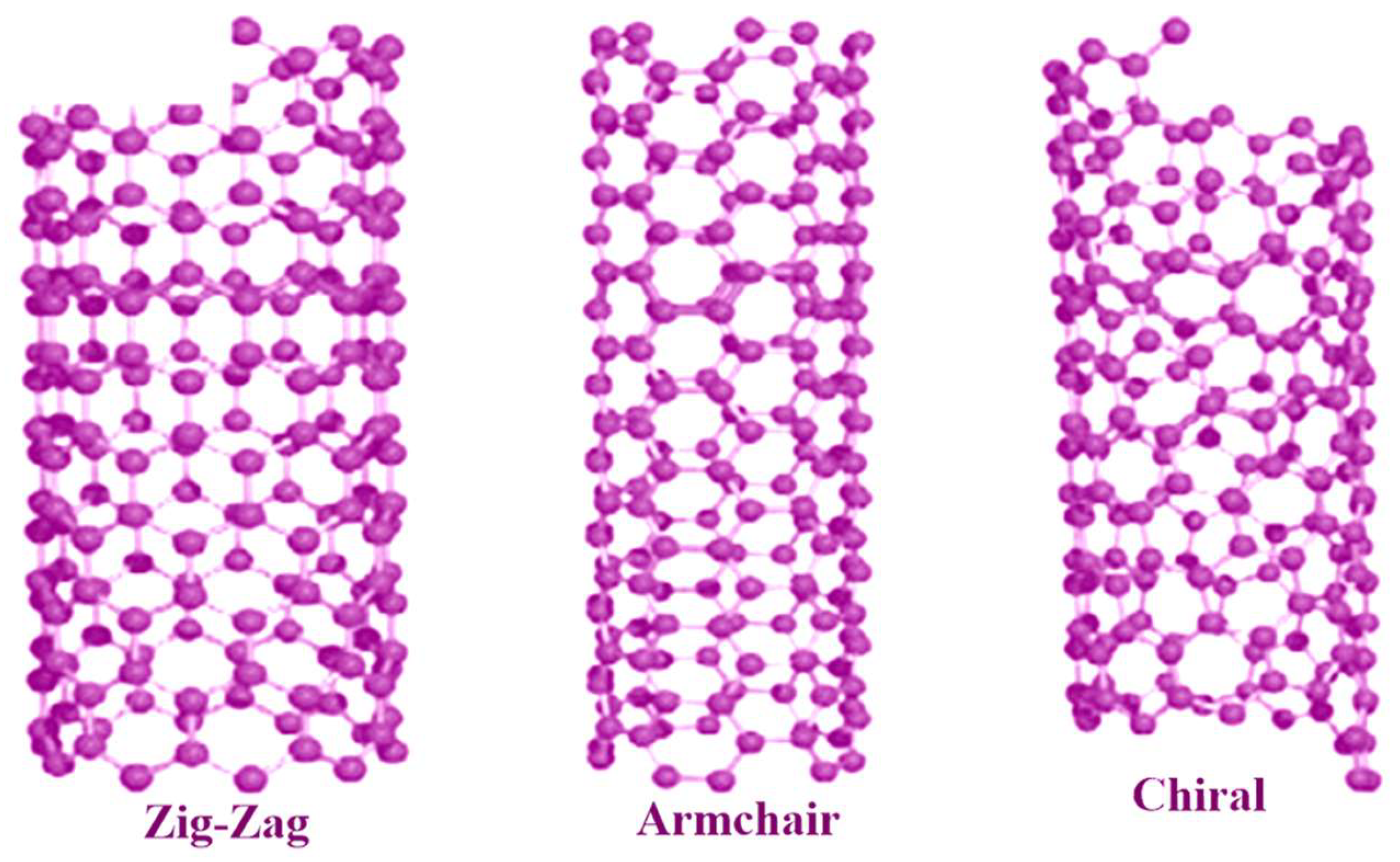

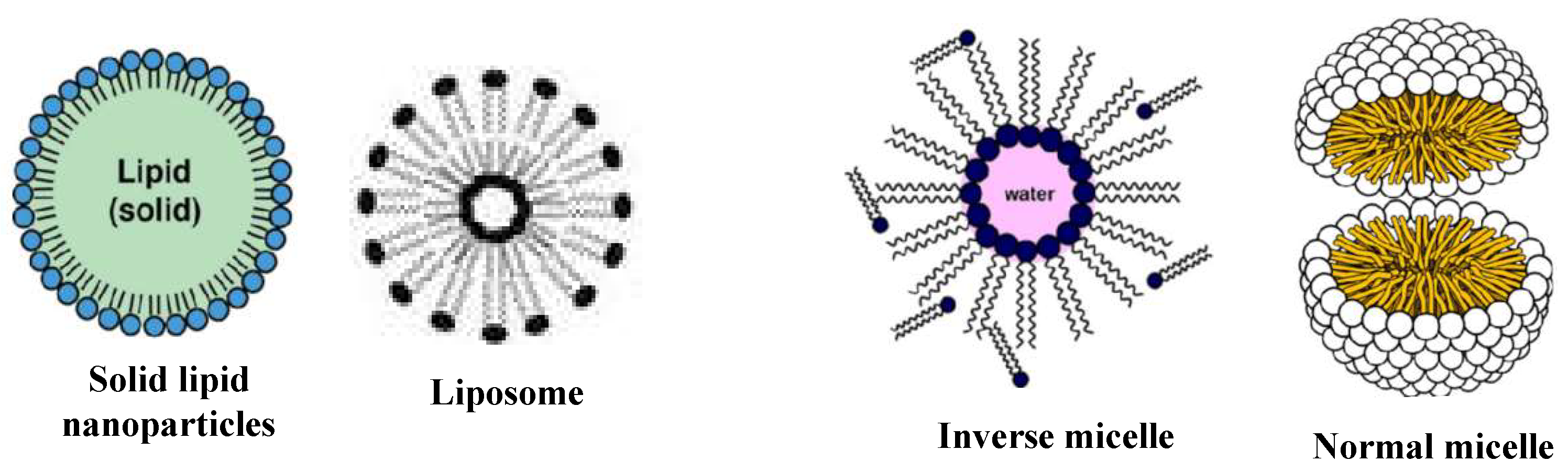

The following classes of NPs are distinguished by their size, shape, and chemical makeup. NPs based on Carbon There are two primary kinds of carbon NPs: fullerenes and carbon nanotubes [38]. In fullerenes, the NPs of spherical hollow cages are similar to the allotropic forms of carbon. The high strength, electrical conductivity, electron affinity, and flexibility of their structure make them attractive to the economy. Each pentagonal and hexagonal shape formed by the carbon units in these materials is sp2 hybridized. A carbon nanotube (CNT) differs from a carbon fiber in that it is long and consists of tubular structures Figure 3 and Figure 4. These essentially have the appearance of graphite (Gr) sheets stacked on top of one another. Carbon nanotubes are therefore categorized according to the number of concentric graphene layers: single-walled (SWCNTs), double-walled (DWCNTs), or multi-walled (MWCNTs) [39,40]. NPs based on Ceramics The inorganic, non-metallic components that make up ceramic NPs are heat-treated and chilled to give them certain qualities. They have long-lasting qualities and are known to be heat-resistant. They may exhibit various structures, including amorphous, polycrystalline, dense, porous, or hollow forms. Ceramic NPs have applications in coating, catalysts, and batteries, among other areas [41,42]. Pictorial presentation of NM and clay-based ceramic filters in Figure 5. NPs based on Lipids Their lipid moieties make them useful for a wide range of biological applications. Lipid NPs are spherical and usually have a diameter of 10–1000 nm. Lipid NPs are composed of soluble lipophilic molecules in a matrix surrounding a solid lipid core. Shapes of lipid-based NMs are given in Figure 6. NPs based on Semiconductors Semiconductor NPs share characteristics with both non-metals and metals. Consequently, a variety of applications are made possible by the exceptional chemical and physical properties of semiconductor NPs. In electronics, semiconductor NPs enable the development of high-efficiency transistors, solar cells, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), offering improved miniaturization and energy performance. They can produce transistors, which are faster and smaller electrical devices that are employed in cancer therapy and bioimaging Figure 7 [43]. In environmental science, they are widely used for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants, including organic dyes and industrial waste, under sunlight or UV radiation [44,45]. Additionally, in the biomedical field, they are applied in biosensors, targeted drug delivery, and diagnostic imaging, owing to their excellent surface functionalization and biocompatibility. In addition to their ability to absorb and emit light at certain wavelengths, quantum dots are suited for use in biolabeling and display technologies. Semiconductor NPs generally contribute significantly to the advancement of technology in several sectors, such as electronics, healthcare, and the environment [46,47,48]. NPs based on Polymers Two categories of active ingredients are utilized in polymeric nanoparticles: surface-adsorbed active ingredients, which adhere to the polymeric substrate, and trapped active ingredients, which are encapsulated within the polymeric substrate. The term polymer NPs is frequently employed in the literature to refer to these NPs, which are often organic. Most of the time, they resemble NPs or nano-capsules, as given in Figure 8 [49,50,51,52]. NPs based on Metals Metal NPs are composed only of metal precursors. In addition to their well-known LSPR sensitivity, these NPs have unique optoelectronic properties. In the visible portion of the solar electromagnetic spectrum, alkali and noble metal NPs, such as Cu, Ag, and Au, occupy a wide absorption band. The regulated synthesis of metal NPs by size, shape, and facet is essential for modern advanced materials [54].

![Figure 8: Schematic of polymer-coated inorganic nanoparticles. (a) Surface functionalization with PEG, thermoresponsive, zwitterionic, and multicoordinating polymers, (b) Cyclic PAOXA-coated nanoparticles providing compact and stable coverage, (c) Star-shaped PAOXA-coated nanoparticles with multiple arms for dense functionalization and enhanced stability. (Reproduced from [53]).](/uploads/source/articles/sustainable-processes-connect/2025/volume1/20250011/image008.png)

Nanomaterials (NMs) possess several properties that influence their behavior at the nanoscale, in addition to surface charge, interactions, crystallography, composition, and surface area. It is well known that atoms, bulk materials, and nanoscale materials have very different characteristics[55]. The NPs must be meticulously regulated to ensure their proper functioning and purity. Two critical factors influence nanomaterial performance and properties: their surface area and surface-to-volume ratio. For surface area calculations, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method is the most widely used [56]. There is a strong correlation between the chemical composition and purity of nanoparticles and their functionality. Additionally, nanoparticle surface charge influences interactions with their targets. There are several ways to quantify the surface charge of a substance and the surface stability of a solution. These methods include the Zeta Potential method. Nanoparticles and targets interact because of a charge on their surface (or the overall charge on the nanoparticles). 8.1. NMs Physical Properties Nanomaterials tend to reduce melting points as the particle size decreases. This decrease is resulting from the fact that their surface atoms are not bound to the surface of the particle [57]. Bulk materials increase their surface area when divided into nanoscale materials, but their volume remains the same. Nanoscale materials have higher surface-to-volume ratios than bulk materials. Molecules or atoms on surfaces possess significant surface energy and typically aggregate [58]. This is one of the most well-known physical properties of nanomaterials, which differ significantly from those of their bulk counterparts in a wide range of parameters. Several factors contribute to the increased surface-to-volume ratio of these materials, including their quantum size effects. The particle size, shape, composition, and surface chemistry of the particles can be altered to tailor these properties. In Table 2, the key physical properties of NMs are summarized. There is strong potential for their application in a wide range of fields, such as electronics, catalysis, biomedical engineering, and environmental remediation. Physical properties of Nanomaterials (NMs) and their characteristic effects at the nanoscale. 8.2. NPs Magnetic Properties The size of NPs can affect an element’s magnetic behavior at the nanoscale. When bulk magnetic materials are nanostructured, the curvature results in a hard or soft magnetic substance with improved nanoscale properties. The critical grain size can enhance the coercivity of the material as well as its superparamagnetic behavior. Materials that are non-magnetic in bulk can exhibit magnetic properties at the nanoscale. For instance, gold (Au) and platinum (Pt) are non-magnetic in bulk but display magnetic behavior at the nanoscale. As shown in Figure 9, magnetic NPs can be used for biomedical applications such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic fluid hyperthermia, and medication delivery [59,60,61,62]. 8.3. NMs Optical Characteristics In NPs, localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) is an optical property. The size of the NPs influences the line width. The emission light position of Au NPs migrates from the near-infrared (NIR) region to the ultraviolet (UV) region as their size decreases. NPS can lose their LSPR due to their tiny size and become photoluminescent. The nanoscale dimensions of NMs can be tuned to control visible light emission as a result of quantum confinement. It has been discovered that as the size of the NMs diminishes, the peak emission shifts toward shorter wavelengths. Nanoscale color changes occur in matter; for instance, gold (Au) nanospheres can shift from yellow at 100 nm to red at 25 nm, greenish yellow at 50 nm, and orange at 200 nm. In addition, silver (Ag) can also transition from light blue at 90 nm to blue at 40 nm, which is the spherical thin film length [63,64]. 8.4. NMs Electrical Properties The electrical conductivity of ceramics can be enhanced by NMs, whereas the mechanical resistance of metals can be improved through their incorporation. Due to the delocalization of electron conduction in bulk materials, electrons may move freely in any direction. It is the quantum effect that is responsible for electron delocalization on nanorods, nanotubes, and nanowires at the nanoscale. Electron confinement causes conducting materials to exhibit discrete energy states instead of continuous energy bands, resulting in both semiconductor and insulator behavior. This result indicates that the metal is evolving into a semiconductor. Carbon nanotubes can function as conductors or semiconductors based on their nanostructure. 8.5. NMs Chemical Properties The stability, sensitivity, and reactivity of NPs with their targets, influenced by environmental factors such as heat, moisture, and light, as well as their chemical composition, determine their potential applications. Applications are partly determined by the NPs’ flammability, anti-corrosive properties, and their oxidation and reduction potentials. There are significant improvements or novel catalytic properties in NMs over bulk catalysts, including reactivity, selectivity, and catalytic activity [14,60]. 8.6. NMs Mechanical Properties The mechanical characteristics of materials, including their flexibility, elasticity, tensile strength, and ductility, are crucial to their application. In the case of nanomaterials (NMs), their mechanical attributes, such as toughness, elastic modulus, yield strength, and hardness, differ significantly from those of bulk materials. As grain size and grain boundary deformation decrease, the strength and hardness of nanostructured materials increase. (The decrease in defect probability and increase in grain boundary refinement contribute to the rise in mechanical strength. It enhanced ceramic super-plasticity, alloy toughness, and hardness [65,66]. NMs exhibit exceptional mechanical properties, such as enhanced strength, hardness, elasticity, and wear resistance, due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio, grain refinement, and defect-free crystal structures. At the nanoscale, the mechanical behavior of materials often deviates from their bulk counterparts because dislocation movement, a key mechanism for deformation, is restricted. For instance, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene possess tensile strengths far exceeding those of steel, making them ideal reinforcements in lightweight, high-strength composites used in aerospace and automotive industries [67]. Similarly, nano-crystalline metals, such as copper and nickel, demonstrate superior hardness and resistance to fatigue, enabling their application in wear-resistant coatings and micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS). Textile industries also benefit from NMs that are more mechanically resilient. In protective clothing and filtration systems, nanofibers produced via electrospinning are suitable because of their enhanced flexibility, tensile strength, and breathability. Nanomaterials such as graphene and nanowires, which are both stretchable and strong, are also employed in the fabrication of flexible electronics and wearable devices. Implants and scaffolds fabricated from NMs need to be mechanically robust to be effective in biomedical engineering. Nanostructured titanium alloys, such as those based on titanium, provide excellent strength-to-weight ratios, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility for orthopedic and dental implants. Hyaluronic acid nanoparticles are incorporated into polymeric scaffolds to mimic bone’s physical and biological properties, helping promote osteointegration [68]. Moreover, medical devices and surgical tools with nanoscale silver and zinc oxide coatings have improved mechanical durability and antimicrobial protection. MMSs possess the ability to create robust, efficient, and versatile products customized to particular requirements due to their mechanical advantages. Understanding these qualities is essential for optimizing materials for technological and biological purposes.

S. No.

Property

Description/Effect at the Nanoscale

Remarks

1.

Particle Size

1–100 nm

Determines surface-to-volume ratio

2.

Surface Area

Very high (up to 1000 m2/g)

Enhances reactivity and adsorption

3.

Melting Point

Often lower than the bulk material

Due to high surface energy

4.

Electrical Conductivity

Enhanced or tunable (e.g., CNTs, graphene)

Depending on the structure and doping

5.

Magnetic Behavior

Superparamagnetic in magnetic NPs

Observed in Fe3O4, Co, Ni NPs

6.

Optical Properties

Size-dependent (quantum confinement)

Color and bandgap shift in quantum dots

7.

Mechanical Strength

High strength-to-weight ratio (e.g., CNTs, graphene)

Useful in composites and coatings

There is a complex relationship between the size, shape, and structure of nanomaterials, as well as their distinct properties. These factors greatly influence the electromagnetic, optical, electronic, and catalytic properties of these materials. The surface-to-volume ratio of particles is strongly correlated with particle size, resulting in a predominance of surface atoms with high reactivity as particle size increases. It is possible for magnetic nanoparticles, in this case Fe3O4, to exhibit superparamagnetic properties below a threshold of 20 nanometers. Due to this phenomenon, magnets can respond rapidly to external electromagnetic fields without retaining any residual magnetism. There are many biomedical applications resulting from this phenomenon, including targeted drug delivery and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [69]. The shape and size of nanoparticles, particularly noble metals such as gold and silver, have a significant impact on their optical properties. There is a phenomenon known as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which occurs when conduction electrons oscillate in response to incident light being directed at gold nanoparticles (Au NPs). Accordingly, the size and morphology of the nanoparticles have a considerable influence on their absorption peaks. At 520 nm, the LSPR radiates red light as a result of the localized surface plasmon resonance of gold sphere nanoparticles. Alternatively, anisotropic shapes such as rods and stars exhibit a resonance shift that favors the near-infrared region, which facilitates the use of such shapes in photothermal therapy and biosensor applications [70]. In semiconducting quantum dots, quantum confinement effects directly influence the band gap. Smaller dots exhibit larger band gaps and shorter wavelengths of light, facilitating tunable fluorescence applicable in bioimaging and LEDs. The properties of nanomaterials can be affected by structural defects, crystallinity, and surface functionalization, which in turn impact their stability and performance. An effective strategy for nanotechnology design is grounded in comprehending the correlation between nanostructure and its properties. Researchers can customize nanomaterials for targeted applications in medicine, electronics, and environmental remediation by adjusting structural parameters.

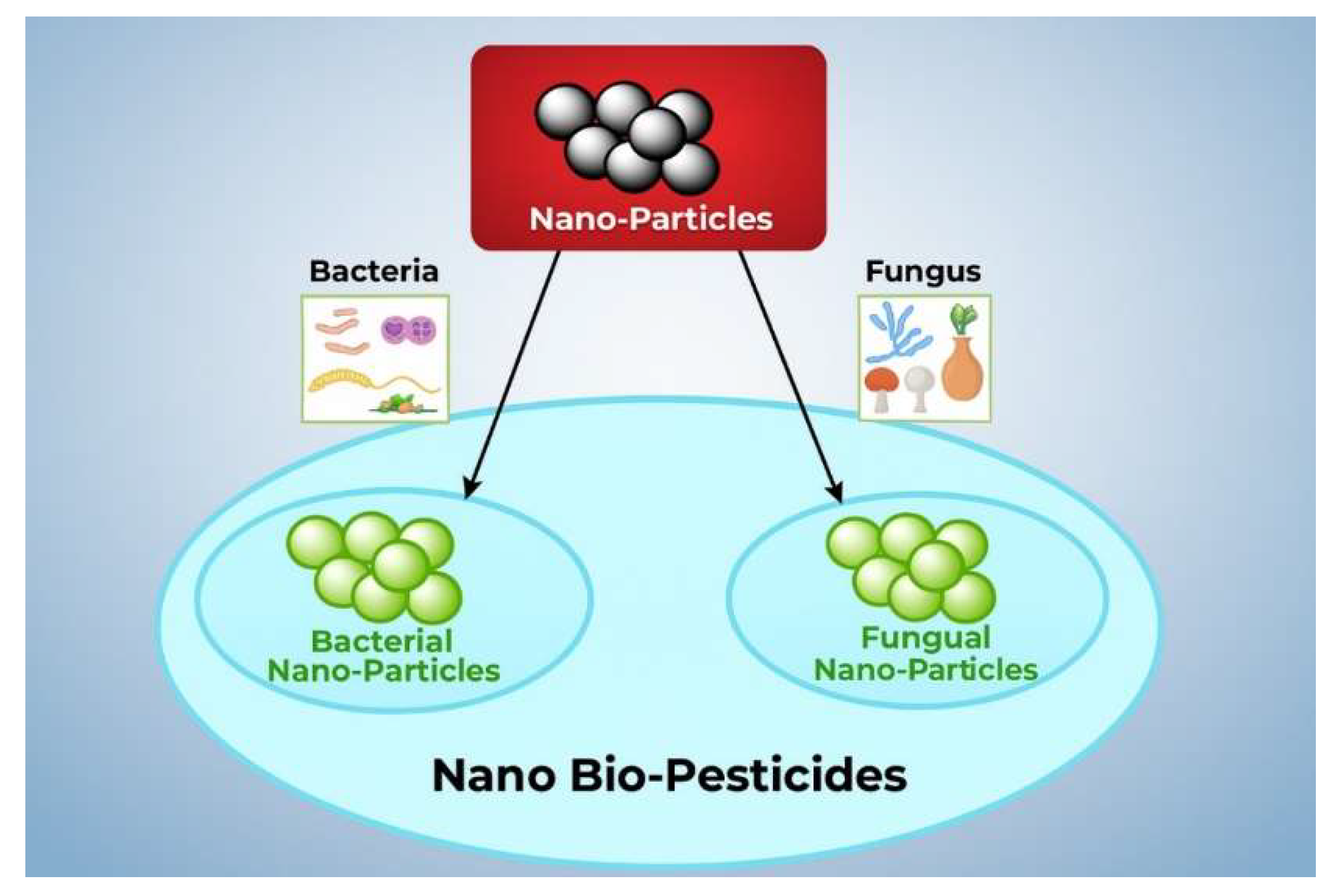

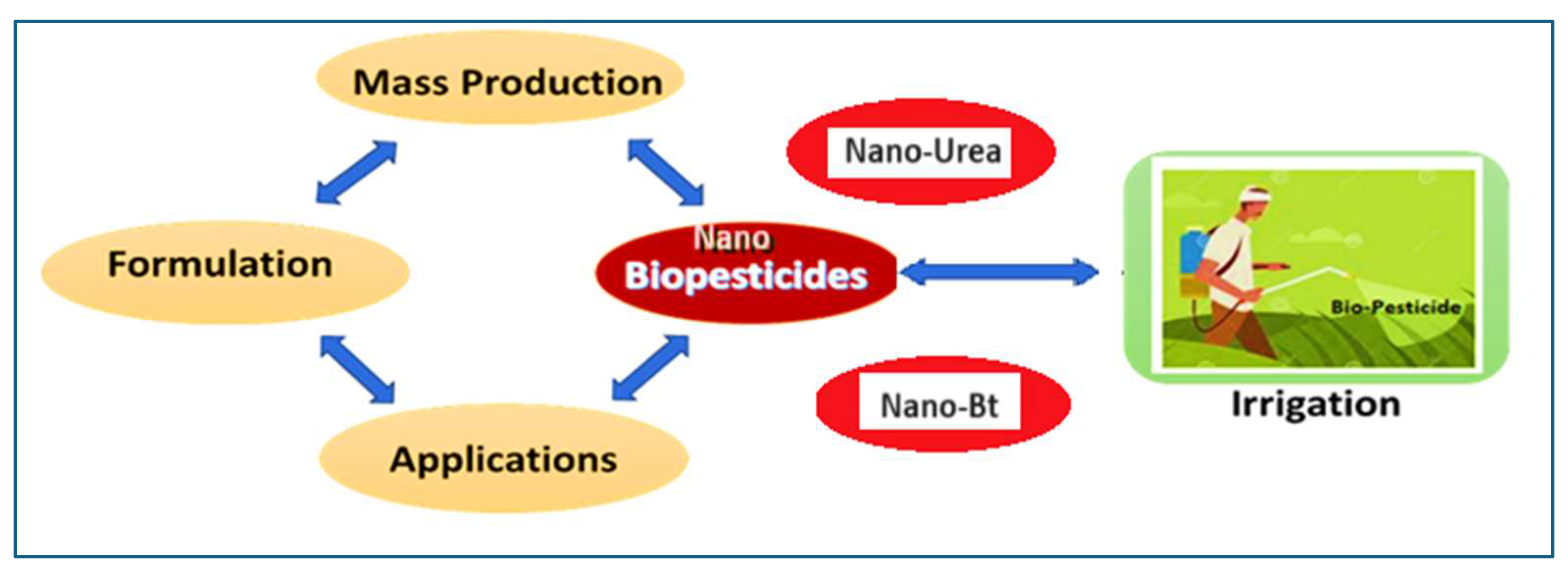

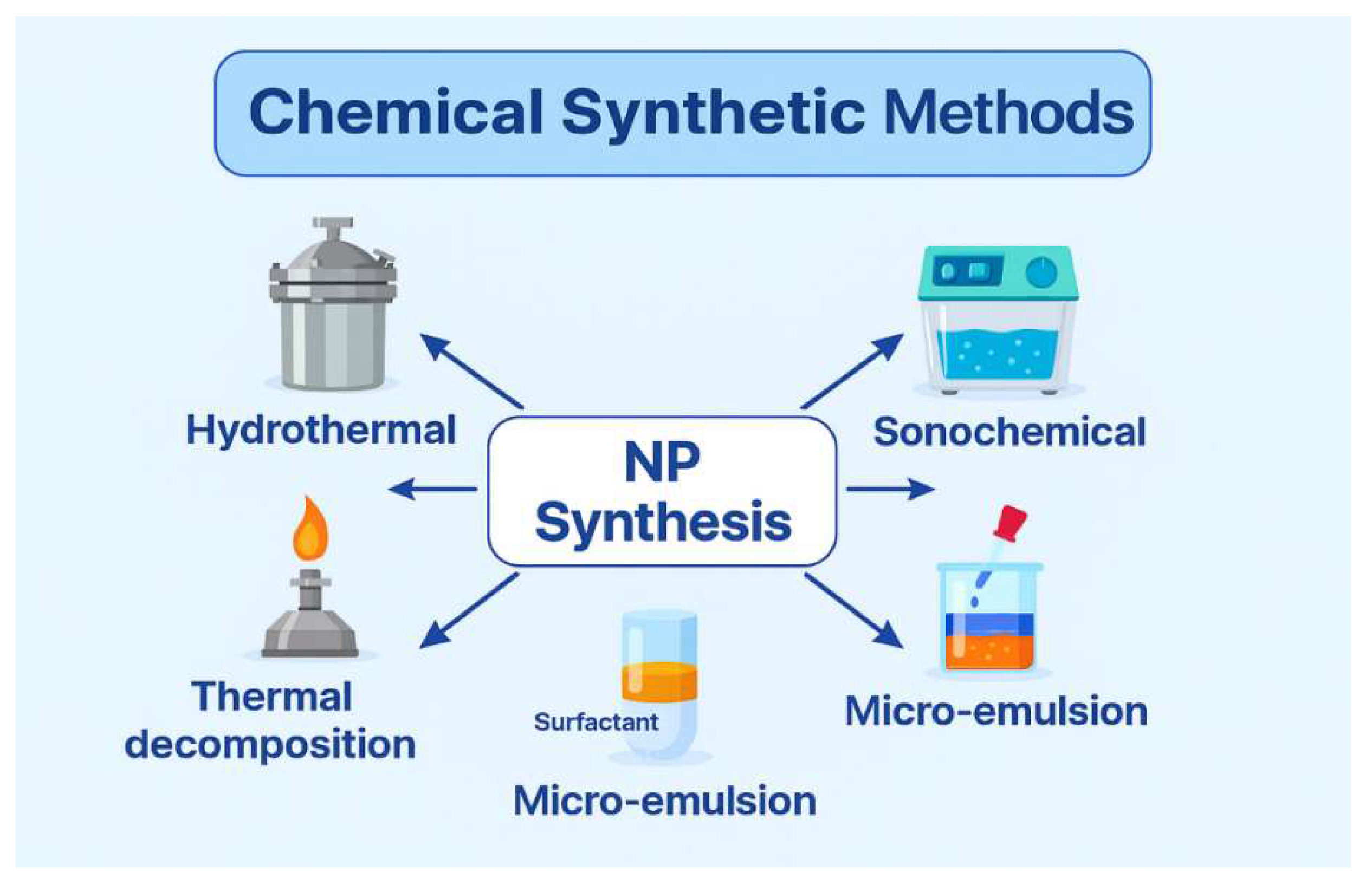

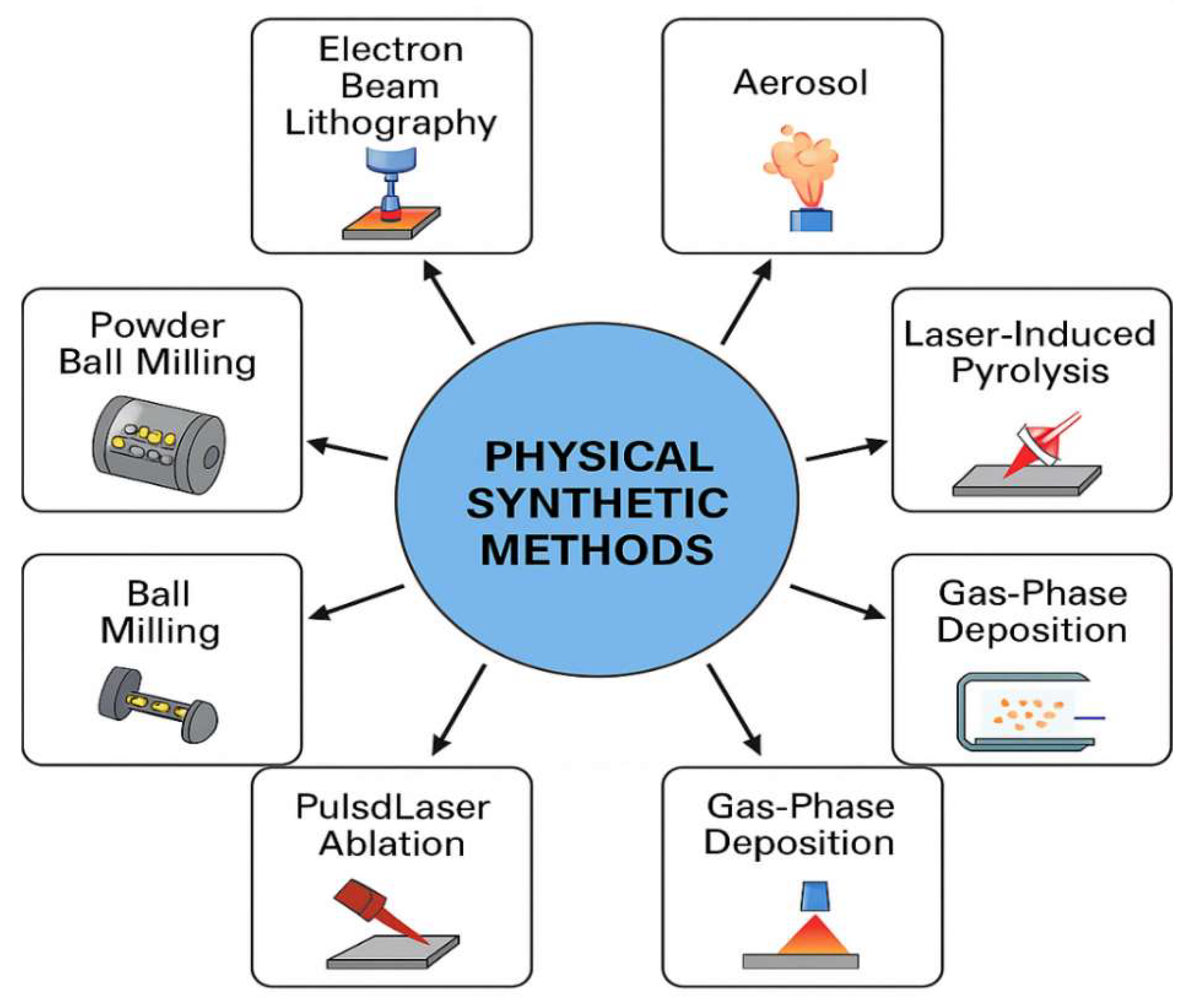

NPs can be synthesized using three main approaches: biological, chemical, and physical. The synthesis of NMs is a rapidly evolving field, providing various techniques to control particle size, morphology, composition, and functionality. Each synthesis method, whether chemical, physical, or biological, has unique advantages and limitations that significantly influence the choice of method depending on the intended application, scalability, cost, and desired material properties. 10.1. Biological Synthetic Methods The biological method is advantageous for the environment and is generally straightforward, requiring only one step. In this sense, we can use various plant components and microbes to make the NMs, such as: 10.2. NMs from Microorganisms Numerous organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and algae, can create a large number of NPs from an aqueous solution of metal salts as given in Figure 10. 10.3. NMs from Bacteria Living organisms produce NPs through biomineralization mediated by proteins. For example, magnetotactic bacteria use magnetosomes to synthesize nanosized magnetic iron oxide crystals, which function as a compass to orient themselves toward their preferred anaerobic habitats on the ocean floor. It has been demonstrated that homogeneous particles with core diameters between 20 and 45 nm can be synthesized in vitro. Magnetosomes, however, contain potent magnetic properties that are valuable in medical applications, such as hyperthermia [71,72,73]. In a study by He et al., gold NPs of 10–20 nm were synthesized using bacteria that produce photosynthesis, such as Rhodopseudomonas capsulata, ex vivo. The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride-dependent reductase enzyme plays a key role in reducing gold ions into NPs. They determined that the growth media’s pH influences the NPs’ shape and form [74]. Schluter et al. reported that extracellular palladium NPs were produced using Pseudomonas bacteria from the alpine location [75]. 10.4. NMs from Fungus Fusarium oxysporum was the fungus used to make extracellular Ag NPs. These NPs long-term stability is ascribed to NADH-enzymatic reductase activity. More protein is released by fungal cells than by bacterial cells [76]. Nowadays, T. reesei is widely employed in the paper, culinary, pharmaceutical, textile, and animal supply industries. Moreover, it is widely used in agricultural irrigation as depicted in Figure 11. Green synthesis techniques utilize plants, bacteria, fungi, or algae to produce NPs in an environmentally friendly and biocompatible manner. These methods are cost-effective and eliminate toxic solvents, making them highly suitable for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. However, the biological variability, slow reaction rates, and challenges in controlling particle size and shape remain significant drawbacks. 10.5. Chemical Synthetic Methods In the chemical approach, various techniques are employed, including hydrothermal synthesis, sonochemical methods, coprecipitation, microemulsion, electrochemical methods, and thermal decomposition. To create magnetic NPs for use in medical imaging applications, a variety of chemical techniques are used, including micro-emulsions, hydrothermal processes, sol-gel synthesis, hydrolysis, flow injection synthesis, precursor thermolysis, and electrospray syntheses [77]. An ideal precursor should be low-cost, minimally volatile, thermally stable, chemically pure, and free of risks associated with chemical vapor deposition. Moreover, following its breakdown, no contaminants ought to remain [78]. Ni and Co catalysts are used in the chemical vapor deposition procedure to produce multilayer graphene (Gr), while a Cu catalyst produces monolayer graphene. Chemical vapor deposition is a widely used technique that yields high-quality NMs in general and is also well-suited for producing two-dimensional NPs [66,79]. Novel NMs are routinely synthesized via wet chemical methods such as the sol-gel process. Numerous high-quality metal-oxide-based NMs could be produced using this technique. Other advantages of the low-cost sol-gel technology are its ability to generate complex nanostructures and composites easily, its production of homogenous material, and its low processing temperature [80]. This process produces small, monodispersed nanoparticles, demonstrating the efficacy of the reverse micelle method for generating magnetic lipase-immobilized nanoparticles [81]. There has been an increase in interest in microwave-assisted hydrothermal techniques among engineers working with nanomaterials recently, as it integrates both microwaves and thermal methods in achieving successful results [82]. Hydrothermal and solvothermal processes have proven to be effective methods for synthesizing a broad range of nanogeometries, including nanorods, nanosheets, nanowires, and nanospheres [83] (Figure 12). The versatility of these processes and their ability to precisely control the size and composition of nanoparticles make them important for making nanoparticles, such as sol-gel, co-precipitation, hydrothermal, and microencapsulation. The sol-gel method can be used to synthesize metal oxides and hybrid nanostructures, as well as achieve uniform particle distribution, facilitate low-temperature processing, and facilitate straightforward doping with additional elements. Due to the limitations of this method, factors such as extended processing times, precursor costs, and potential solvent contamination must be considered. As an alternative to hydrothermal or solvothermal methods, which are associated with high-pressure reactors and present scalability constraints, this method produces high-crystallinity nanostructures at moderate temperatures and pressures. Despite its simplicity, co-precipitation often results in a broad size distribution and low crystallinity, making it suitable for producing large quantities of bulk materials, although achieving high purity can be challenging. 10.6. Physical Methods The process involves powder ball milling, electron beam lithography, aerosols, laser-induced pyrolysis, gas-phase deposition, and pulsed laser ablation [84,85]. Through laser ablation synthesis, nanomaterials are synthesized by the generation of nanoparticles [86]. The original material is vaporized by a laser ablation procedure, causing it to disappear. In the subsequent steps, a high-intensity laser is employed to produce nanoparticles. In addition to oxide composites, metal nanoparticles, ceramics, and carbon nanoparticles, there are several other nanomaterials that can be prepared with this method [87]. There is a process called lithography that involves the focusing of beams of light or electrons to create architectures that are small and precise. This technique involves the use of prefabricated masks on a substrate to transfer nanoparticle patterns across a large area through mask lithography. As an alternative to photolithography and nanoimprint lithography, soft lithography can be used for mask lithography [88]. In terms of cost-effectiveness, mechanical milling is a highly effective method for breaking down larger particles to produce products on the nanoscale. Additionally, mechanical milling may also be used as a method for forming nanocomposites by combining different phases through the combination of specific mechanical processes [89]. The use of ball-milled carbon nanoparticles can be used for a variety of applications, including energy conversion, environmental remediation, and energy storage, among others [90]. The electrospinning process is an inexpensive and straightforward way of producing nanostructured materials. Polymers are the most common type of nanofiber-forming polymer. The method provides a means of producing hollow polymers, inorganic materials, organic compounds, core-shell structures, and hybrid materials, which include hollow polymers, inorganic materials, organic compounds, and hybrid materials. This type of deposition involves the ejection of small atom clusters from a surface using gaseous ions for bombardment and is part of a process known as sputter deposition[91] Figure 13. It has been shown that nanomaterials can be produced without the use of chemical reagents by a variety of techniques, including ball milling, laser ablation, sputtering, and electron beam lithography. As a method of particle size reduction, alloy synthesis, and the synthesis of nanocomposite materials, top-down ball milling is an effective method for particle size reduction. This method of particle size control appears to be both cost-effective and scalable; however, it displays limitations regarding the precision of particle size control, as well as causing structural defects in the final product. When laser ablation is combined with solid targets, highly pure nanoparticles are produced with virtually no contaminants present. In contrast, the high costs of equipment and low yields generally make it an unsuitable technology for large-scale production due to the high equipment costs. The precise control of nanoscale patterning and film deposition in applications related to electronics and photonics depends on techniques such as sputtering and lithography. Despite the high operating costs, complex configuration, and limited throughput, these systems are still limited to a number of specific applications because of their high costs and complexity. To summarize, there are two general approaches to synthesizing NMs: top-down and bottom-up. There are several advantages and disadvantages to each methodology, along with its set of methodologies. Top-down approaches involve the reduction of bulk materials into nanoscale structures using methods such as milling, lithography, or laser ablation. This approach generates a lot of NMs and is scalable, but it has little control over the generation of surface defects, particle size, and shape. The bottom-up method employs chemical techniques, including sol-gel synthesis, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), hydrothermal processing, and biological synthesis, to construct nanostructures at the atomic or molecular level. The capacity to manipulate particle size, shape, and composition through these techniques renders nanomaterials suitable for customization to particular applications. A bottom-up approach typically requires expensive precursors and conditions and can be more complex and time-consuming (Table 3). In sol-gel synthesis, uniform metal oxide nanoparticles are produced under mild conditions, whereas in CVD, well-defined structures are produced, making them ideal for thin films and coatings. There is growing interest in biological synthesis due to its environmentally friendly and non-toxic nature, although challenges related to reproducibility and scalability persist [9]. In the case of bulk production applications, physical methods are preferred, while chemical and biological methods are best suited to high-precision applications in electronics, medicine, and catalysis. The selection of a synthesis technique is contingent upon the intended properties of the final nanomaterial, application specifications, cost factors, and environmental implications. Comparative analysis of Nanomaterial synthesis methods. The most appropriate research and industrial strategy can be selected only after a thorough evaluation of each method’s merits and limitations is completed. A comparative perspective enables informed decision-making in the development of NMs and promotes the advancement of sustainable and innovative technologies. Sputtering is a preferred method because it is less expensive than electron-beam lithography and has a composition that is more similar to the target material with fewer flaws.

S. No.

Synthesis Method

Type

Advantages

Limitations

1.

Sol-Gel

Chemical

- Uniform particle distribution—Low processing temperature

-Good for oxides and composites- Long processing time

- Risk of contamination from solvents

- Costly precursors

2.

Co-precipitation

Chemical

- Simple and low-cost

- Scalable

- Mild reaction conditions- Poor control over particle size

- Low crystallinity

3.

Hydrothermal/

SolvothermalChemical

- High crystallinity

- Good morphology control

- Suitable for complex structures- Requires high-pressure autoclaves

- Limited scalability

4.

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

Chemical

- High-purity products

- Thin film and 2D material synthesis

- Precise control- Expensive setup

- High energy use

- Toxic precursors

5.

Ball Milling

Physical

- Inexpensive

- Scalable

- Suitable for alloy and composite formation- Broad particle size distribution

- Structural defects

6.

Laser Ablation

Physical

- High-purity NPs

- No chemical contamination

- Applicable to many materials- Low yield

- High equipment cost

- Limited scalability

7.

Sputtering

Physical

- Excellent film quality

- Good compositional fidelity

- Reproducible- Expensive

- Low deposition rate

- Complex instrumentation

8.

Electron Beam Lithography

Physical

- High-resolution patterning

- Suitable for electronics

- Precise fabrication- Time-consuming

- High-cost

- Limited to small areas

9.

Electrospinning

Physical/Chemical

- Easy nanofiber production

- Core-shell and hybrid nanostructures

- Low-cost- Limited to fibrous structures—Sensitive to ambient conditions

This study has provided a comprehensive introduction to NMs, highlighting their classification, synthesis methods, and applications in various industries. Key findings include the distinct size-dependent properties of NMs, which differentiate them from bulk materials in terms of magnetic, electrical, optical, chemical, and mechanical behaviors. These properties arise due to quantum effects, surface interactions, and high surface-to-volume ratios. The review also emphasized the importance of both top-down and bottom-up synthesis techniques, including physical, chemical, and biological methods, each of which offers unique advantages for producing nanostructures tailored to specific applications. A comprehensive classification based on size, shape, and composition is essential for understanding nanoparticle behavior and optimizing their applications in nanotechnology. Integrating recent advances helps in designing next-generation NPs for safer and more efficient use across sectors. Despite significant advancements in nanomaterial synthesis and characterization, challenges remain in scaling up production, ensuring environmental sustainability, and controlling the toxicity of certain NMs. The need for standardized methods for assessing the environmental and health impacts of NMs is crucial for their widespread adoption. Future research directions should focus on the development of more efficient, cost-effective, and eco-friendly synthesis routes, as well as exploring novel NMs for advanced applications in fields such as energy storage, environmental remediation, and medicine. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to overcome current barriers and fully harness the potential of NMs for future innovations.

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscope |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (method) |

| CNTs | Carbon Nanotubes |

| DWCNTs | Double-Walled Carbon Nanotubes |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| MEMS | Micro-Electromechanical Systems |

| MoS2 | Molybdenum Disulfide |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MWCNTs | Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NMs | Nanomaterials |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| STM | Scanning Tunnelling Microscope |

| SWCNTs | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

Writing—Original Draft: A.K., S.M., M.E.K.; Writing—Review & Editing: A.G. and H.K.; Conceptualization: S.M.; Methodology: A.K., S.M.; Validation: A.K., S.M.; Formal Analysis: A.K., S.M., A.G. and H.K., S.H.; Investigation: A.K., S.M., A.G. and H.K.; Resources: A.K., S.M.; Data Curation: A.K., S.M., S.H.; Figure Designing and Visualization: A.K., S.M., S.H.; Supervision: S.M., M.E.K.; Project Administration: S.M., M.E.K.; Funding Acquisition: NA; All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors declare that no known competing financial interests or personal relationships may have influenced any of the material included in this publication.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

The authors are highly thankful to Uttaranchal University, Patliputra University, and Jazan University for their support and time. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used [ChatGPT/Deepseek] solely for improving language clarity and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article. No AI tools were used to generate or interpret scientific data, draw conclusions, or influence the study’s methodology.

[1] Toumey, C. Reading Feynman Into Nanotechnology: A Text for a New Science. Techne Res. Philos. Technol. 2008, 12, 133–168. [CrossRef]

[2] Khatoon, U.T.; Velidandi, A. An Overview on the Role of Government Initiatives in Nanotechnology Innovation for Sustainable Economic Development and Research Progress. Sustainability 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

[3] Zahoor, M.; Nazir, N.; Iftikhar, M.; Naz, S.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Uddin, F.; Kamran, A.W.; Kallistova, A.; Pimenov, N. A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods of Synthesis, and Their Potential Roles in Biomedical Applications and Water Treatment. Water 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

[4] Pathakoti, K.; Goodla, L.; Manubolu, M.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanoparticles and Their Potential Applications in Agriculture, Biological Therapies, Food, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Nanotechnology and Nanomaterial Applications in Food, Health, and Biomedical Sciences ; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ, USA, 2019; 121–162. . [CrossRef]

[5] Harish, V.; Tewari, D.; Gaur, M.; Yadav, A.B.; Swaroop, S.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Review on Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Materials: Bioimaging, Biosensing, Drug Delivery, Tissue Engineering, Antimicrobial, and Agro-Food Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

[6] Dolai, J.; Mandal, K.; Jana, N.R. Nanoparticle Size Effects in Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6471–6496. [CrossRef]

[7] Hill, J.M. A Review of de Broglie Particle–Wave Mechanical Systems. Math. Mech. Solids 2020, 25, 1763–1777. [CrossRef]

[8] Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9] Kirubakaran, D.; Wahid, J.B.A.; Karmegam, N.; Jeevika, R.; Sellapillai, L.; Rajkumar, M.; SenthilKumar, K. A Comprehensive Review on the Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Advancements in Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 24, 1–26. [CrossRef]

[10] Farooq, M.A.; Hannan, F.; Islam, F.; Ayyaz, A.; Zhang, N.; Chen, W.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhou, W. The Potential of Nanomaterials for Sustainable Modern Agriculture: Present Findings and Future Perspectives. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 1926–1951. [CrossRef]

[11] Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shu, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, H.; Tao, W. Insights from Nanotechnology in COVID-19 Treatment. Nano Today 2021, 36, 101019. [CrossRef]

[12] Mohamed, N.A.; Zupin, L.; Mazi, S.I.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Crovella, S. Nanomedicine as a Potential Tool Against Monkeypox. Vaccines 2023, 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13] Khandelwal, N.; Kaur, G.; Chaubey, K.K.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Tiwari, A.; Singh, S.V.; Kumar, N. Silver Nanoparticles Impair Peste des Petits Ruminants Virus Replication. Virus Res. 2014, 190, 1–7. [CrossRef]

[14] Alvand, Z.M.; Rajabi, H.R.; Mirzaei, A.; Masoumiasl, A. Ultrasonic and Microwave Assisted Extraction as Rapid and Efficient Techniques for Plant Mediated Synthesis of Quantum Dots: Green Synthesis, Characterization of Zinc Telluride and Comparison Study of Some Biological Activities. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 15126–15138. [CrossRef]

[15] Poh, T.Y.; Ali, N.A.t.B.M.; Mac Aogáin, M.; Kathawala, M.H.; Setyawati, M.I.; Ng, K.W.; Chotirmall, S.H. Inhaled Nanomaterials and the Respiratory Microbiome: Clinical, Immunological and Toxicological Perspectives. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 46. [CrossRef]

[16] Muchtaromah, B.; Habibie, S.; Ma’arif, B.; Ramadhan, R.; Savitri, E.S.; Maghfuroh, Z. Comparative Analysis of Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Activity of Ethanol Extract of Centella Asiatica Leaves and Its Nanoparticle Form. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 5, 465–469. [CrossRef]

[17] Buzea, C.; Pacheco, I.I.; Robbie, K. Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles: Sources and Toxicity. Biointerphases 2007, 2, MR17–MR71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[18] Findik, F. Particulate Composites, Analysis Techniques and Applications. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2024, 12, 37–54. [CrossRef]

[19] Torgal, F.P.; Jalali, S. Toxicidade de Materiais de Construção: Uma Questão Incontornável na Construção Sustentável. Ambiente Construído 2010, 10, 41–53. [CrossRef]

[20] Srivastava, R.; Thakur, A.; Rana, A. The Basic Understanding of Nano Materials: A Review. Innov. Nanomater.-Based Corros. Inhib. 2024, , 1–20. [CrossRef]

[21] Bhardwaj, L.K.; Rath, P.; Choudhury, M. A Comprehensive Review on the Classification, Uses, Sources of Nanoparticles (NPs) and Their Toxicity on Health. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2023, 7, 69–86. [CrossRef]

[22] Radulescu, D.-M.; Surdu, V.-A.; Ficai, A.; Ficai, D.; Grumezescu, A.-M.; Andronescu, E. Green Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review of the Principles and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

[23] Alexandru, I.; Davidescu, L.; Motofelea, A.C.; Ciocarlie, T.; Motofelea, N.; Costachescu, D.; Marc, M.S.; Suppini, N.; Șovrea, A.S.; Coșeriu, R.-L. Emerging Nanomedicine Approaches in Targeted Lung Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

[24] Pisano, R.; Durlo, A. Nanosciences and Nanotechnologies: A Scientific–Historical Introductory Review. Nanoscience & Nanotechnologies. Nanotechnology in the Life Sciences ; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; 3–90. . [CrossRef]

[25] Kokarneswaran, M.; Selvaraj, P.; Ashokan, T.; Perumal, S.; Sellappan, P.; Kandhasamy, D.M.; Mohan, N.; Chandrasekaran, V. Carbon Nanotubes in Keeladi Potteries. ChemRxiv 2020, . [CrossRef]

[26] Khonina, S.N.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Skidanov, R.V.; Butt, M.A. Advancements and Applications of Diffractive Optical Elements in Contemporary Optics: A Comprehensive Overview. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2025, 10, 2401028. [CrossRef]

[27] Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Ansari, M.A.; Cheng, H.; Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, S. Design Strategies and Applications of Dimensional Optical Field Manipulation Based on Metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208884. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28] Prabowo, B.A.; Purwidyantri, A.; Liu, K.-C. Surface Plasmon Resonance Optical Sensor: A Review on Light Source Technology. Biosensors 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

[29] Wang, B.; Yu, P.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Kuo, H.C.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.M. High-Q Plasmonic Resonances: Fundamentals and Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2001520. [CrossRef]

[30] Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and Surface Engineering of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [CrossRef]

[31] Lage, T.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Catarino, S.; Gallo, J.; Bañobre-López, M.; Minas, G. Graphene-Based Magnetic Nanoparticles for Theranostics: An Overview for Their Potential in Clinical Application. Nanomaterials 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

[32] Chen, L.; Lai, I.-L.; Murugan, K.; Shyu, D.J. Unveiling the Potential Activities of Myriad Carbonaceous Nanomaterials in Scaling and Fabrication of Miniaturized, Sensitive, and Economical Medical Diagnostic Kits. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Biosystems ; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; 475–499. . [CrossRef]

[33] Mikhlin, Y.L.; Vorobyev, S.A.; Saikova, S.V.; Vishnyakova, E.A.; Romanchenko, A.S.; Zharkov, S.M.; Larichev, Y.V. On the Nature of Citrate-Derived Surface Species on Ag Nanoparticles: Insights from X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 687–694. [CrossRef]

[34] Alberti, G.; Zanoni, C.; Magnaghi, L.R.; Biesuz, R. Gold and Silver Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Sensors: New Trends and Applications. Chemosensors 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

[35] Yaqoob, A.A.; Umar, K.; Ibrahim, M.N.M. Silver Nanoparticles: Various Methods of Synthesis, Size Affecting Factors and Their Potential Applications–A Review. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 1369–1378. [CrossRef]

[36] Beyene, H.D.; Werkneh, A.A.; Bezabh, H.K.; Ambaye, T.G. Synthesis Paradigm and Applications of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), a Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 13, 18–23. [CrossRef]

[37] Giljohann, D.A.; Seferos, D.S.; Daniel, W.L.; Massich, M.D.; Patel, P.C.; Mirkin, C.A. Gold Nanoparticles for Biology and Medicine. Spherical Nucleic Acids 2020, 49, 3280–3294. [CrossRef]

[38] Vir Singh, M.; Kumar Tiwari, A.; Gupta, R. Catalytic Chemical Vapor Deposition Methodology for Carbon Nanotubes Synthesis. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202204715. [CrossRef]

[39] Astefanei, A.; Núñez, O.; Galceran, M.T. Characterisation and Determination of Fullerenes: A Critical Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 882, 1–21. [CrossRef]

[40] Elliott, J.A.; Shibuta, Y.; Amara, H.; Bichara, C.; Neyts, E.C. Atomistic Modelling of CVD Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6662–6676. [CrossRef]

[41] Sigmund, W.; Yuh, J.; Park, H.; Maneeratana, V.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Daga, A.; Taylor, J.; Nino, J.C. Processing and Structure Relationships in Electrospinning of Ceramic Fiber Systems. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 395–407. [CrossRef]

[42] Shivaraju, H.P.; Egumbo, H.; Madhusudan, P.; Anil Kumar, K.; Midhun, G. Preparation of Affordable and Multifunctional Clay-Based Ceramic Filter Matrix for Treatment of Drinking Water. Environ. Technol. 2019, 40, 1633–1643. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[43] Biju, V.; Itoh, T.; Anas, A.; Sujith, A.; Ishikawa, M. Semiconductor Quantum Dots and Metal Nanoparticles: Syntheses, Optical Properties, and Biological Applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 2469–2495. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[44] Roushani, M.; Mavaei, M.; Rajabi, H.R. Graphene Quantum dots as Novel and Green Nano-Materials for the Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Cationic Dye. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 409, 102–109. [CrossRef]

[45] Yadav, S.; Shakya, K.; Gupta, A.; Singh, D.; Chandran, A.R.; Varayil Aanappalli, A.; Goyal, K.; Rani, N.; Saini, K. A Review on Degradation of Organic Dyes by Using Metal Oxide Semiconductors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 71912–71932. [CrossRef]

[46] Feng, L.; Song, S.; Li, H.; He, R.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, X. Nano-Biosensors Based on Noble Metal and Semiconductor Materials: Emerging Trends and Future Prospects. Metals 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

[47] Din, M.I.; Khalid, R.; Hussain, Z. Recent Research on Development and Modification of Nontoxic Semiconductor for Environmental Application. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2021, 50, 244–261. [CrossRef]

[48] Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Howlader, A.S.; Mim, J.J.; Islam, S.; Arup, M.M.R.; Hossain, N. Advantages of Narrow Bandgap Nanoparticles in Semiconductor Development and Their Applications. Semiconductors 2024, 58, 849–873. [CrossRef]

[49] Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A.M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Nagasamy Venkatesh, D.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Eder, P.; Silva, A.M.; Santini, A. Polymeric Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization, Toxicology and Ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[50] Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, Applications and Toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [CrossRef]

[51] Khan, M.E.; Mohammad, A.; Ali, W.; Imran, M.; Bashiri, A.H.; Zakri, W. Properties of Metal and Metal Oxides Nanocomposites. Nanocomposites-Advanced Materials for Energy and Environmental Aspects ; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; 23–39. . [CrossRef]

[52] Khan, M.E.; Mohammad, A.; Cho, M.H. Nanoparticles Based Surface Plasmon Enhanced Photocatalysis. Green Photocatalysts ; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; 133–143. . [CrossRef]

[53] Komsthöft, T.; Bovone, G.; Bernhard, S.; Tibbitt, M.W. Polymer Functionalization of Inorganic Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 37, 100849. [CrossRef]

[54] Dreaden, E.C.; Alkilany, A.M.; Huang, X.; Murphy, C.J.; El-Sayed, M.A. The Golden Age: Gold Nanoparticles for Biomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2740–2779. [CrossRef]

[55] Patil, S.A.; Jagdale, P.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.V.; Khan, Z.; Samal, A.K.; Saxena, M. 2D Zinc Oxide–Synthesis, Methodologies, Reaction Mechanism, and Applications. Small 2023, 19, 2206063. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[56] Wohlleben, W.; Mielke, J.; Bianchin, A.; Ghanem, A.; Freiberger, H.; Rauscher, H.; Gemeinert, M.; Hodoroaba, V.-D. Reliable Nanomaterial Classification of Powders Using the Volume-Specific Surface Area Method. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2017, 19, 61. [CrossRef]

[57] Vollath, D.; Fischer, F.D.; Holec, D. Surface Energy of Nanoparticles–Influence of Particle Size and Structure. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 2265–2276. [CrossRef]

[58] Ouyang, G.; Wang, C.; Yang, G. Surface Energy of Nanostructural Materials with Negative Curvature and Related Size Effects. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4221–4247. [CrossRef]

[59] Kumar, A.; Bisht, G.; Siddiqui, N.; Masroor, S.; Mehtab, S.; Zaidi, M. Synthesis of Magnetic Hydrogels for Target Delivery of Doxorubicin. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 2019, 11, 1071–1074. [CrossRef]

[60] Khalid, K.; Tan, X.; Mohd Zaid, H.F.; Tao, Y.; Lye Chew, C.; Chu, D.-T.; Lam, M.K.; Ho, Y.-C.; Lim, J.W.; Chin Wei, L. Advanced in Developmental Organic and Inorganic Nanomaterial: A Review. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 328–355. [CrossRef]

[61] Fang, J.; Chen, Y.-C. Nanomaterials for Photohyperthermia: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6622–6634. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[62] Flores-Rojas, G.G.; López-Saucedo, F.; Vera-Graziano, R.; Mendizabal, E.; Bucio, E. Magnetic Nanoparticles for Medical Applications: Updated Review. Macromol 2022, 2, 374–390. [CrossRef]

[63] Huynh, K.-H.; Pham, X.-H.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.H.; Chang, H.; Rho, W.-Y.; Jun, B.-H. Synthesis, Properties, and Biological Applications of Metallic Alloy Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

[64] Horikoshi, S.; Serpone, N. . Microwaves in Nanoparticle Synthesis: Fundamentals and Applications ; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; . . [CrossRef]

[65] Cho, G.; Park, Y.; Hong, Y.-K.; Ha, D.-H. Ion Exchange: An Advanced Synthetic Method for Complex Nanoparticles. Nano Converg. 2019, 6, 1–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[66] Khan, Y.; Sadia, H.; Ali Shah, S.Z.; Khan, M.N.; Shah, A.A.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, M.F.; Bibi, H.; Bafakeeh, O.T.; Khedher, N.B. Classification, Synthetic, and Characterization Approaches to Nanoparticles, and Their Applications in Various Fields of Nanotechnology: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

[67] Baig, Z.; Mamat, O.; Mustapha, M. Recent Progress on the Dispersion and the Strengthening Effect of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene-Reinforced Metal Nanocomposites: A Review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2018, 43, 1–46. [CrossRef]

[68] El-Bassyouni, G.T.; Mouneir, S.M.; El-Shamy, A.M. Advances in Surface Modifications of Titanium and Its Alloys: Implications for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2025, 8, 265. [CrossRef]

[69] Anderson, S.D.; Gwenin, V.V.; Gwenin, C.D. Magnetic Functionalized Nanoparticles for Biomedical, Drug Delivery and Imaging Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 188. [CrossRef]

[70] Hang, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, N. Plasmonic Silver and Gold Nanoparticles: Shape-and Structure-Modulated Plasmonic Functionality for Point-of-Caring Sensing, Bio-Imaging and Medical Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2932–2971. [CrossRef]

[71] Krishnan, K.M. . Fundamentals and Applications of Magnetic Materials ; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; . . [CrossRef]

[72] Faivre, D.; Schuler, D. Magnetotactic Bacteria and Magnetosomes. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4875–4898. [CrossRef]

[73] Rajabi, H.R.; Sajadiasl, F.; Karimi, H.; Alvand, Z.M. Green Synthesis of Zinc Sulfide Nanophotocatalysts Using Aqueous Extract of Ficus Johannis Plant for Efficient Photodegradation of Some Pollutants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15638–15647. [CrossRef]

[74] He, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Gu, N. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using the Bacteria Rhodopseudomonas Capsulata. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 3984–3987. [CrossRef]

[75] Schlüter, M.; Hentzel, T.; Suarez, C.; Koch, M.; Lorenz, W.G.; Böhm, L.; Düring, R.-A.; Koinig, K.A.; Bunge, M. Synthesis of Novel Palladium (0) Nanocatalysts by Microorganisms from Heavy-Metal-Influenced High-alpine Sites for Dehalogenation of Polychlorinated Dioxins. Chemosphere 2014, 117, 462–470. [CrossRef]

[76] Ahmad, A.; Mukherjee, P.; Senapati, S.; Mandal, D.; Khan, M.I.; Kumar, R.; Sastry, M. Extracellular Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Fungus Fusarium Oxysporum. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2003, 28, 313–318. [CrossRef]

[77] Elfeky, A.S.; Salem, S.S.; Elzaref, A.S.; Owda, M.E.; Eladawy, H.A.; Saeed, A.M.; Awad, M.A.; Abou-Zeid, R.E.; Fouda, A. Multifunctional Cellulose Nanocrystal/Metal Oxide Hybrid, Photo-Degradation, Antibacterial and Larvicidal Activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115711. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[78] Jones, A.C.; Hitchman, M.L. . Chemical Vapour Deposition: Precursors, Processes and Applications ; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2009; . . [CrossRef]

[79] Paras; Yadav, K.; Kumar, P.; Teja, D.R.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Sahoo, A.; Chou, M.M.; Liang, C.-T. A Review on Low-Dimensional Nanomaterials: Nanofabrication, Characterization and Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[80] Parashar, M.; Shukla, V.K.; Singh, R. Metal Oxides Nanoparticles via Sol–Gel Method: A Review on Synthesis, Characterization and Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 3729–3749. [CrossRef]

[81] Yi, S.; Dai, F.; Zhao, C.; Si, Y. A Reverse Micelle Strategy for Fabricating Magnetic Lipase-Immobilized Nanoparticles with Robust Enzymatic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

[82] Devi, N.; Sahoo, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.K. A Review of the Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Carbon Nanomaterials, Metal Oxides/Hydroxides and Their Composites for Energy Storage Applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11679–11711. [CrossRef]

[83] Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Properties, Recent Progress, and Challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [CrossRef]

[84] Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Liu, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W. Laser Synthesis and Microfabrication of Micro/Nanostructured Materials Toward Energy Conversion and Storage. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 49. [CrossRef]

[85] Krishna Podagatlapalli, G. The Fundamentals of Synthesis of the Nanomaterials, Properties, and Emphasis on Laser Ablation in Liquids: A Brief Review. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[86] Kim, M.; Osone, S.; Kim, T.; Higashi, H.; Seto, T. Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Laser Ablation: A Review. KONA Powder Part. J. 2017, 34, 80–90. [CrossRef]

[87] Zhi, M.; Xiang, C.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Wu, N. Nanostructured Carbon–Metal Oxide Composite Electrodes for Supercapacitors: A Review. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 72–88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[88] Baek, D.; Lee, S.H.; Jun, B.-H.; Lee, S.H. Lithography Technology for Micro-and Nanofabrication. Nanotechnology for Bioapplications ; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; 217–233. . [CrossRef]

[89] Paul, A.; Lopez-Vidal, L.; Paredes, A.J. Progress in the Production of Nanocrystals Through Miniaturised Milling Methods. RPS Pharm. Pharmacol. Rep. 2025, 4, rqaf008. [CrossRef]

[90] Lyu, H.; Gao, B.; He, F.; Ding, C.; Tang, J.; Crittenden, J.C. Ball-Milled Carbon Nanomaterials for Energy and Environmental Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9568–9585. [CrossRef]

[91] Mattox, D. Particle Bombardment Effects on Thin-Film Deposition: A Review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1989, 7, 1105–1114. [CrossRef]

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more