APA Style

Avanish Kumar, Ashish Kapoor, Amit Kumar Rathoure, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. (2025). Organic Compounds Removal Using Magnetic Biochar from Textile Industries Based Wastewater-A Comprehensive Review. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0012). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.147565MLA Style

Avanish Kumar, Ashish Kapoor, Amit Kumar Rathoure, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. "Organic Compounds Removal Using Magnetic Biochar from Textile Industries Based Wastewater-A Comprehensive Review". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0012, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.147565.Chicago Style

Avanish Kumar, Ashish Kapoor, Amit Kumar Rathoure, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. 2025. "Organic Compounds Removal Using Magnetic Biochar from Textile Industries Based Wastewater-A Comprehensive Review." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0012. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.147565.

ACCESS

Review Article

ACCESS

Review Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0012

Avanish Kumar

akumarch@hbtu.ac.in

Ashish Kapoor

ashishk@hbtu.ac.in

Amit Kumar Rathoure

amitrathoure@hbtu.ac.in

Girdhari Lal Devnani

gldevnani@hbtu.ac.in

Dan Bahadur Pal

dbpal@hbtu.ac.in

Department of Chemical Engineering, Harcourt Butler Technical University, Kanpur Uttar Pradesh 208002, India

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 22 May 2025 Accepted: 25 Aug 2025 Available Online: 27 Aug 2025 Published: 12 Sep 2025

Textile industries are among the largest contributors to global water pollution, discharging wastewater containing dyes, heavy metals, and synthetic chemicals that pose significant environmental and health risks. Conventional treatment methods often fall short in effectively removing these pollutants and are hindered by high operational costs, sludge production, and limited reusability. In this context, magnetic biochar has emerged as a promising, sustainable, and cost-effective solution for textile wastewater remediation. This review examines the synthesis strategies of magnetic biochar, primarily focusing on co-precipitation and iron-precursor pyrolysis methods, along with their key physicochemical and magnetic properties, characterized by XRD, SEM, BET, FTIR, and VSM analyses. The adsorption behavior of magnetic biochar is further discussed through isotherm and kinetic models, such as Langmuir, Freundlich, pseudo-second-order, and intra-particle diffusion. The mechanisms driving pollutant removal include electrostatic attraction, pore filling, π–π interactions, and catalytic Fenton-like catalytic reactions. Case studies on dye and heavy metal removal demonstrate the material’s high efficiency, ease of recovery, and reusability. Finally, the paper highlights current research gaps, scalability challenges, and prospects for advancing magnetic biochar technologies in industrial-scale wastewater treatment. This review provides a comprehensive understanding to guide future innovations and practical applications in sustainable water management.

Organic compounds removal using magnetic biochar from textile industries wastewater Methods used conventional treatment methods, economic, and cost-effective adsorbents Adsorption isotherm and kinetic models for magnetic biochar from textile industries wastewater Adsorption mechanisms of magnetic biochar adsorbent, like pore filling, π–π interactions, etc.

Water is one of the most essential natural resources for life on Earth, however, only a small fraction is readily available and safe for human consumption. The Earth is often referred to as the “blue planet” because about 71% of its surface is covered with water [1]. However, a closer examination reveals that only a tiny fraction of this water is accessible for direct human use. Approximately 97.5% of the total water on Earth is saline, found in oceans and seas, and is not suitable for drinking, irrigation, or most industrial purposes without undergoing expensive desalination processes [2]. This leaves only 2.5% of the Earth’s water as freshwater, which could, in principle, support human needs. However, this freshwater is not entirely accessible. Approximately 68.7%, is stored in glaciers and ice caps, primarily in Antarctica and Greenland [3]. Another 30.1% is stored underground in aquifers, some of which are deep and not easily accessible or renewable [4]. That leaves just a small fraction, around 1.2% of the total freshwater available in surface water bodies such as rivers, lakes, and swamps. It is well known that only about 0.007% of the Earth’s total freshwater is available for human consumption, which amounts to roughly 0.03% of the planet’s total volume of water [5]. This small quantity of water is needed for drinking, sanitation, agriculture, industry, and ecosystem maintenance. Due to population growth, urbanization, and industrial development, freshwater availability is becoming a serious concern. The imbalance between supply and demand is leading to water shortages and degraded water quality, making effective water management more urgent than ever. Water pollution has become one of the most serious global issues, arising from both domestic and industrial sources [6]. Industrial wastewater is of complex composition and contains toxic pollutants. The textile industries are known for their high-water consumption and discharge of chemically loaded wastewater into the river [7]. When released into rivers, lakes, or groundwater, this water can cause severe harm to aquatic life and pose significant risks to human health [8]. Textile wastewater is highly toxic because it contains dyes, surfactants, salts, heavy metals (such as chromium, copper, and zinc), and various organic chemicals [9]. During processes like dyeing, washing, and bleaching, a significant portion of the used chemicals is not fixed onto the fabric and is instead released into wastewater streams. Dyes, particularly synthetic and azo dyes, are resistant to degradation and can remain in water bodies for extended periods, obstructing sunlight penetration and disrupting photosynthetic activity in aquatic plants [10]. The high biological and chemical oxygen demand (BOD and COD) of textile wastewater further depletes dissolved oxygen in water, posing a threat to aquatic organisms [11]. Although conventional wastewater treatment methods, such as coagulation-flocculation, activated sludge processes, and membrane filtration, have been widely employed to manage textile effluents [12]. While these methods can reduce pollutant loads, they often fall short in completely removing synthetic dyes and trace heavy metals. Moreover, these technologies are energy-intensive, generate secondary sludge that requires further treatment, and are expensive to operate and maintain, particularly for small to medium-scale textile units in developing countries. The inefficiency in dealing with non-biodegradable organic pollutants and the economic burden of advanced methods like reverse osmosis or advanced oxidation processes further highlight the need for more sustainable and cost-effective alternatives [13]. In recent years, biochar produced through the pyrolysis of biomass has emerged as a promising adsorbent for wastewater treatment [14]. Due to its porous structure, large surface area, and abundant surface functional groups, biochar can effectively adsorb a wide range of pollutants, including dyes, heavy metals, and organic compounds. Moreover, biochar is eco-friendly, cost-effective, and can be derived from agricultural waste such as water hyacinth, rice husk, coconut shells, and other biomass. These materials can be used to prepare biochar, which is then treated with Fe3O4 to produce magnetic biochar through either the impregnation-pyrolysis method with iron precursors or the co-precipitation technique. This study examines twenty types of biomass to understand the behavior of bioadsorbents in terms of their adsorption capacity and removal efficiency. To enhance its performance, biochar is often modified with magnetic particles like iron oxide, resulting in magnetic biochar. This composite not only improves pollutant removal efficiency through combined adsorption and catalytic degradation but also facilitates easy recovery and reuse using magnetic separation [15]. Thus, biochar and magnetic biochar represents sustainable, low-cost, and effective alternatives to traditional treatment technologies, offering new hope for addressing the challenges of industrial wastewater, particularly from the textile sector [16]. Figure 1 illustrates the various types of biomass used for the preparation of biochar and magnetic biochar.

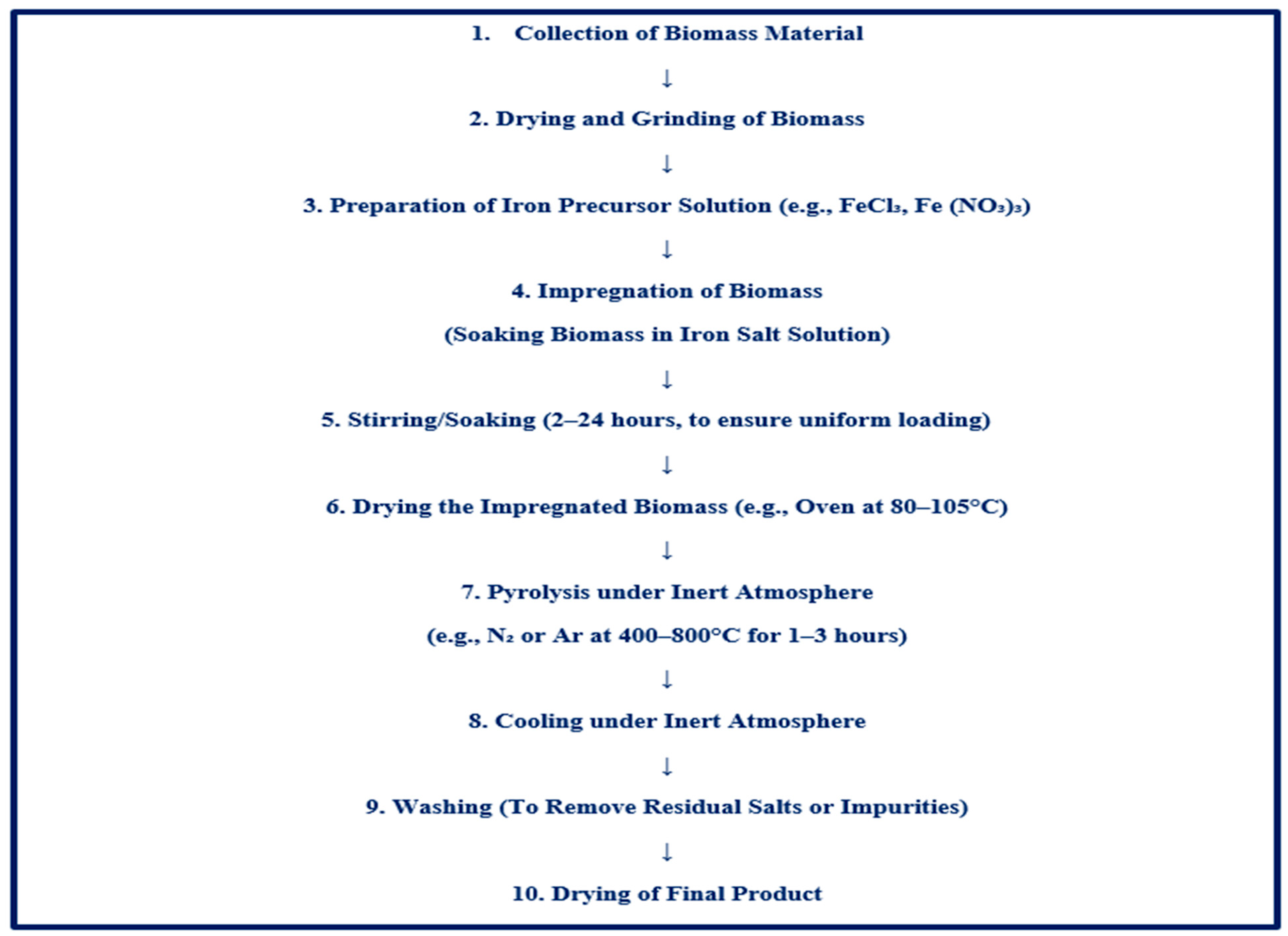

Biochar is a carbon-rich, porous solid produced through the pyrolysis of organic biomass under limited oxygen conditions [17]. This process thermally decomposes plant-based or organic materials, such as agricultural residues, forestry waste, or aquatic plants like water hyacinth, to form a stable carbonaceous structure. The characteristics of the resulting biochar depend on factors such as the type of biomass used, pyrolysis temperature, residence time, and heating rate [18]. For instance, low-temperature pyrolysis (300–500 °C) retains more oxygenated functional groups and volatile matter, while high-temperature pyrolysis (above 600 °C) yields biochar with higher carbon content, surface area, and porosity. These properties make biochar effective for pollutant adsorption; however, unmodified biochar often shows limited affinity for specific contaminants, such as dyes or heavy metals [19]. As a result, researchers have explored chemical and structural modifications to enhance its adsorptive performance, leading to the development of magnetic biochar. This magnetic functionality allows for the efficient removal and recycling of the adsorbent from aqueous solutions using an external magnetic field. There are two methods, namely the co-precipitation technique and the impregnation-pyrolysis method, which are used as iron precursors. These can be explained as follows: 2.1. Co-Precipitation Technique The co-precipitation method is one of the most widely used and straightforward techniques for synthesizing magnetic biochar, primarily due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency in producing uniformly dispersed magnetic nanoparticles. In this process, the biochar produced from pyrolysis is immersed in an aqueous solution containing ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) ions, commonly provided by ferrous chloride (FeCl2) and ferric chloride (FeCl3) in a 1:2 molar ratio, respectively [20]. Once the biochar is well-treated with an iron salt solution, and a base such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) is gradually added dropwise under constant stirring, where the pH of the mixture is carefully adjusted to around 10, creating alkaline conditions that are essential for the simultaneous precipitation (co-precipitation) of iron ions. Under these conditions, the Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions react with hydroxide ions (OH−) to form magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4) and produce a porous structure of the biochar [21]. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram to prepare Magnetic Biochar by the Co-precipitation Technique. This step is typically followed by an aging process, where the suspension is allowed to stand or continue stirring for a designated period (e.g., several hours) at room temperature or mild heating to ensure complete precipitation and strong adhesion of Fe3O4 nanoparticles onto the biochar matrix [22]. The resulting magnetic biochar is then separated from the liquid phase through filtration or magnetic decantation, followed by repeated washing with deionized water or ethanol to remove unreacted chemicals, excess salts, and impurities. Finally, the washed material is dried at moderate temperatures (e.g., 60–80 °C) to obtain the magnetic biochar composite. The magnetization of the biochar imparts a superparamagnetic or ferromagnetic character, allowing it to be easily separated from aqueous solutions using a simple external magnet [23]. This precipitated composite can be used for dye adsorption. The detailed flow diagram for the preparation of magnetic biochar using the co-precipitation technique is discussed as follows in Figure 2: 2.2. Impregnation and Pyrolysis with Iron Precursors In contrast to the co-precipitation method, the impregnation and pyrolysis technique involves introducing iron precursors into the raw biomass before the pyrolysis stage [24]. In this step, the dried biomass is immersed in a solution of iron salts, such as FeCl3 or Fe(NO3)3, allowing the metal ions to penetrate the plant structure. After sufficient impregnation, the biomass is dried and then subjected to pyrolysis at elevated temperatures (typically 500–700 °C). During the heating process, the iron salts thermally decompose into iron oxides such as Fe2O3 or Fe3O4, forming a biochar matrix. This method ensures a strong bond between magnetic particles and the carbon structure, often resulting in more stable and efficient magnetic biochar for pollutant removal [25]. Magnetic biochar produced by either method is particularly effective for the removal of dyes, heavy metals, and other industrial pollutants [26]. Figure 3 shows the flow diagram to prepare magnetic biochar by impregnation and pyrolysis with iron precursors. Table 1 shows the comparison of the Co-precipitation Technique and Impregnation and Pyrolysis with Iron Precursors method. 3. Characterization Techniques of Magnetic Biochar Several advanced techniques are required to analyze the physicochemical structure of bioadsorbents. These techniques evaluate various properties, such as the morphological structure of the bioadsorbent. In addition, other characteristics, including the crystal structure and the presence of organic functional groups in the material, can also be determined [27]. 3.1. Structural and Morphological Analysis (XRD, SEM) X-ray diffraction (XRD) is important for identifying the crystalline phases present in magnetic biochar. It helps to determine the crystal structure of magnetic iron oxides, such as Fe3O4 or Fe2O3, in the carbon matrix. In the case of WH magnetic biochar, XRD patterns typically show distinct peaks around 30°, 35°, 43°, 57°, and 63° (2θ), corresponding to magnetite (Fe3O4) [28]. This confirms the magnetic modification. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provides insight into the morphological structure, revealing a rough, porous texture with uniformly distributed iron oxide particles across the surface. This porous structure is beneficial for the adsorption of dyes and other pollutants [29]. Table 2 presents the comparative analysis of XRD and FTIR Spectra of Biochar and Magnetic Biochar. Comparison of the co-precipitation technique and impregnation and pyrolysis with iron precursors method. Comparative analysis of XRD and FTIR spectra of biochar and magnetic biochar. 3.2. Surface Area and Porosity (BET) The BET analysis is used to determine the specific surface area, pore size distribution, and pore volume of biochar [48]. These properties are directly related to the adsorption potential of the material. A higher surface area provides more active sites for pollutant binding. Magnetic biochar derived from WH often shows an increase in surface area compared to unmodified biochar due to the development of additional microspores during iron incorporation [49]. 3.3. Functional Groups and Surface Chemistry (FTIR) (FTIR) is used to know the functional groups present on the surface of the biochar. These functional groups—such as hydroxyl (-OH), carboxyl (-COOH), and carbonyl (C=O)—play a key role in adsorption through mechanisms like hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction For WH magnetic biochar, FTIR spectra often show peaks related to O–H stretching, C–H bending, and Fe–O vibrations, representing the successful loading of iron oxides and the retention of oxygen-containing groups that contribute to effective dye or heavy metal removal [50]. 3.4. Magnetic Properties (VSM) VSM analysis is conducted to determine the magnetic properties of the synthesized biochar, particularly to assess its suitability for applications involving magnetic separation. VSM is a powerful technique that determines key magnetic parameters such as saturation magnetization (Ms), coercivity (Hc), and remanent magnetization (Mr). These parameters afford the strength of the magnetic response of the material. Magnetic biochar often demonstrates superparamagnetic behavior, which is desirable for environmental remediation [51]. The typical saturation magnetization values for WH-based magnetic biochar range between 10–30 emu/g, which are sufficient for fast and efficient magnetic recovery from aqueous systems. This magnetic recoverability eliminates the need for time-consuming and costly separation methods such as filtration or centrifugation. As a result, magnetic biochar can be easily reused, making it an economical and sustainable solution for wastewater treatment applications [52]. Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of magnetic and non-magnetic biochar in wastewater treatment. Comparative analysis of magnetic vs. non-magnetic biochar in wastewater treatment.

Aspect

Co-Precipitation Technique

Impregnation + Pyrolysis with Iron Precursors

Advantages

Simple and low-cost synthesis

Easy to perform at low temperatures

Simple method for metal loading

Uniform particle distribution

Good control over nanoparticle size and distribution

Reasonable dispersion of iron on biomass

High magnetic properties

Effective in forming magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe3O4) [30]

Magnetic properties retained after pyrolysis

Environmentally friendly

Aqueous medium, minimal toxic solvents

Biomass-based, sustainable approach

Fast reaction time

The co-precipitation Technique requires a short synthesis time [31]

Efficient in bulk production

Disadvantages

pH-sensitive process

Requires precise pH control for precipitation

Not highly pH-sensitive, but the process can affect material structure.

Particle agglomeration

Nanoparticles may cluster without surfactants or stabilizers [32]

Risk of metal sintering or uneven distribution during pyrolysis [33]

Low thermal stability

Not suitable for high-temperature applications

High temperatures may reduce surface area or porosity [34]

Complex post-processing

Requires washing, filtration, and drying

Requires a high-temperature furnace and an inert gas environment

Limited loading capacity

Metal ion incorporation is limited by solubility [35]

Iron loading depends on precursor soaking and biomass reactivity

Biomass Source

Biochar Type/Treatment

XRD Observations

FTIR Observations (Major Functional Groups)

Ref.

Rice Husk

Plain biochar (500 °C)

Broad peak at 2θ ≈ 22–24° (amorphous carbon), sharp peaks at 26.6° (SiO2—quartz)

–OH (3400 cm−1), Si–O–Si (1080 cm−1), C–H (2920 cm−1), C=C (1620 cm−1)

[36]

Rice Husk

Magnetic biochar (FeCl3 impregnation + pyrolysis)

Fe3O4 peaks at 2θ ≈ 30.1°, 35.6°, 43.2°, 57.1°, 62.6°

Fe–O (580–590 cm−1), Si–O–Si (1080 cm−1), –OH (3430 cm−1), C=O (1700 cm−1)

[37]

Water Hyacinth

Plain biochar

Broad hump at 2θ ≈ 23°, small peaks due to CaCO3, SiO2

–OH (3410 cm−1), COOH (1710 cm−1), C=C (1610 cm−1), Si–O (1030 cm−1)

[38]

Water Hyacinth

Magnetic biochar (FeSO4 + FeCl3 co-precipitation)

Fe3O4 peaks + amorphous carbon, Ca-related phases

Fe–O (580 cm−1), C–O–C (1120 cm−1), –OH (3400 cm−1), C=O (1710 cm−1)

[39]

Coconut Shell

Untreated biochar

Broad peak at ~24°, minor inorganic peaks

–OH (3430 cm−1), aromatic C=C (1600 cm−1), C–H (2910 cm−1), C–O (1230 cm−1)

[40]

Coconut Shell

Magnetic biochar (Fe(NO3)3 impregnation)

Peaks of Fe2O3 at ~33.1°, 35.6°, 49.5°

Fe–O (around 570 cm−1), –OH (3400 cm−1), COOH (1705 cm−1)

[41]

Peanut Shell

Biochar at 500 °C

Broad amorphous carbon hump, low crystallinity

–OH (3420 cm−1), C=C (1590 cm−1), C–O (1235 cm−1)

[42]

Peanut Shell

Magnetic biochar with Fe3O4

Characteristic Fe3O4 peaks, better crystallinity

Fe–O (575–590 cm−1), –OH (3425 cm−1), carboxylic C=O (1710 cm−1)

[43]

Corn Stover

ZnCl2-activated biochar

Weak peak at 23°, ZnO or Zn-silicates

Zn–O (520 cm−1), –OH (3400 cm−1), C=O (1710 cm−1), C–H (2915 cm−1)

[44]

Corn Stover

Magnetic biochar with iron salts

Magnetite (Fe3O4) peaks + Zn peaks

Fe–O (580 cm−1), –OH, C=O, C–O observed

[45]

Sawdust

KOH-activated biochar

Broad amorphous carbon peaks, some K2CO3 or KCl

–OH (3435 cm−1), C–O (1100 cm−1), C=C (1600 cm−1), C=O (1700 cm−1)

[46]

Sawdust

Magnetic biochar

Magnetite peaks (Fe3O4), suppressed K signals

Fe–O (580 cm−1), –OH (3400 cm−1), C–H (2910 cm−1), aromatic groups

[47]

S.No.

Biomass Source

Pollutant

Non-Magnetic Biochar Removal Efficiency (%)

Magnetic Biochar Removal Efficiency (%)

Advantages of Magnetic Biochar

Disadvantages of Magnetic Biochar

References

1

Rice Husk

Crystal Violet

~50%

>90%

Enhanced adsorption capacity

Potential for secondary pollution if not properly managed

[53]

2

Coconut Shell

Acid Orange

~60%

>95%

Improved removal efficiency

Increased production cost

[54]

3

Chicken Bones

Rhoda mine B

~45%

75%

Better adsorption kinetics

Possible leaching of iron

[55]

4

Wheat Straw

Methylene Blue

~70%

>90%

Faster equilibrium time

Reduced surface area due to magnetization

[56]

5

Sewage Sludge

Methylene Blue

~54%

~56%

Slight improvement in removal

Marginal benefits over non-magnetic biochar

[57]

6

Partheniumstero phorus

Methylene Blue

94%

99.99%

Significant enhancement in efficiency

Complex synthesis process

[58]

7

Rice Bran

Ni(II)

~60%

>90%

Higher adsorption capacity

Potential environmental risks

[59]

8

Bagasse

Cr(VI)

~50%

>85%

Improved heavy metal removal

Possible iron leaching

[60]

9

Corn Stalk

Pb(II)

~65%

>90%

Enhanced adsorption sites

Higher synthesis cost

[61]

10

Water Hyacinth

Methylene Blue

~70%

>95%

Better pollutant removal

Potential for nanoparticle release

[62]

11

Peanut Shell

Cr(VI)

~55%

>80%

Improved adsorption efficiency

Increased production complexity

[63]

12

Bamboo

Methylene Blue

~60%

>90%

Faster adsorption rates

Potential environmental concerns

[64]

13

Sugarcane Bagasse

Pb(II)

~70%

>95%

Higher removal efficiency

Possible secondary pollution

[65]

14

Corn Cob

Ni(II)

~60%

>85%

Enhanced adsorption capacity

Increased synthesis cost

[66]

15

Sawdust

Cd(II)

~50%

>80%

Improved heavy metal removal

Potential for iron leaching

[67]

16

Algal Biomass

Methylene Blue

~65%

>90%

Better dye removal

Complex preparation process

[68]

17

Fruit Peels

Cr(VI)

~55%

>85%

Enhanced adsorption sites

Higher production cost

[69]

18

Wood Chips

Pb(II)

~60%

>90%

Improved heavy metal removal

Potential environmental risks

[70]

19

Rice Straw

Methylene Blue

~70%

>95%

Higher removal efficiency

Possible nanoparticle release

[71]

20

Orange Peel

Cd(II)

~50%

>80%

Enhanced adsorption capacity

Increased synthesis complexity

[72]

4.1. Adsorption Capabilities Magnetic biochar is a planned material created by integrating magnetic nanoparticles—commonly iron oxides such as Fe3O4 or γ-Fe2O3—into traditional biochar derived from biomass sources like agricultural waste [73]. This modification imparts the resulting composite with distinctive physicochemical and magnetic properties, significantly enhancing its adsorption capacity and facilitating its separation in wastewater treatment applications. A key advantage of magnetic biochar lies in its physicochemical properties, which render it highly effective for the removal of dyes and heavy metals from contaminated water [74]. Its high surface area provides a larger number of active sites for adsorption, while its porous structure—particularly the presence of micro- and mesopores—facilitates the diffusion and trapping of pollutants like dye molecules and metal ions. Furthermore, magnetic biochar surfaces often contain abundant oxygen-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH), carboxyl (–COOH), and amino (–NH2) groups, which actively interact with pollutants through mechanisms like hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and surface complexation [75]. The pH-responsive nature of these functional groups plays a crucial role in adsorption efficiency, particularly for metal ions, as it influences their ionization states and binding affinities. 4.2. Essential Magnetic Property Another distinctive feature of magnetic biochar is its inherent magnetic property, which allows for easy recovery after treatment. This feature provides a significant operational benefit in post-treatment processes. After adsorption, the magnetic biochar can be separated from the treated water using an external magnet [76]. This eliminates the need for multifaceted filtration or centrifugation systems, reduces processing time, and minimizes operational costs. More importantly, it reduces the risk of secondary pollution caused by the loss of fine biochar particles in the effluent stream. Such ease of separation is particularly advantageous in continuous treatment systems or large-scale operations, where time and material recovery are important parameters [77]. 4.3. Performance of Dyes and Heavy Metal Removal In textile wastewater treatment, magnetic biochar has been found to perform well in removing heavy metals and dyes from the solution. Studies have shown that magnetic biochar performs excellently in removing cationic dyes like methylene blue (MB) and anionic dyes like Congo red (CR). These dyes are adsorbed through various mechanisms, including π–π interactions, electrostatic attractions, and pore-filling effects [78]. The Removal efficiencies for methylene blue using magnetic biochar frequently exceed 90–95% under optimal conditions, while Congo red, owing to its anionic nature, is efficiently captured via electrostatic attraction to positively charged functional groups on the biochar surface. In the case of heavy metals such as hexavalent chromium (Cr6+), lead (Pb2+), and copper (Cu2+), magnetic biochar shows strong adsorption through ion exchange, and electrostatic interactions [68] Several studies have reported Cr6+ removal efficiencies close to 98–99%, while Pb2+ and Cu2+ are also effectively removed by interacting carboxyl COOH- and hydroxyl groups OH- group present on the magnetic biochar matrix [79]. In addition to its high adsorption efficiency, magnetic biochar demonstrates excellent regeneration and reusability potential. The Spent magnetic biochar can be regenerated through desorption methods using mild acid, base, or salt solutions, and in some cases, by thermal reactivation. These regeneration methods can restore the adsorption capacity, allowing the biochar to be reused multiple times. Studies show that magnetic biochar retains over 80–90% of its original adsorption performance even after four to five cycles of use [80]. This not only reduces the overall cost of treatment but also contributes to the development of an environmentally friendly and circular water treatment system.

It is important to understand and validate adsorption and kinetic models, as they are fundamental for estimating the efficiency, mechanism, and feasibility of adsorbents in wastewater treatment applications [81]. Adsorption isotherms describe how pollutants interact with the surface of the adsorbent at equilibrium and also help quantify the adsorption capacity. Table 4 presents a comparative review of biochar performance based on pollutant type. Comparative table: biochar performance based on pollutant type. 5.1. Adsorption Isotherm The adsorption kinetic models define the rate at which adsorption occurs and provide information about the rate-controlling steps. It is important to understand adsorption isotherms and kinetic models to know the feasibility of adsorbents in wastewater treatment and how pollutants interact with the surface of the adsorbent at equilibrium, helping to determine the adsorption capacity [92]. One of the most widely used isotherms is the Langmuir model, which assumes monolayer adsorption onto a homogeneous surface with finite, identical sites. This model is particularly useful for predicting maximum adsorption capacities and aids in the design of adsorption systems for industrial applications. While with the help of the Freundlich isotherm accounts for multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface and is better suited for describing adsorption in real and complex systems such as textile wastewater containing multiple pollutants [93]. Figure 4a shows single-layer adsorption, and Figure 4b Multilayer adsorption process. Additionally, the Temkin isotherm considers the effect of indirect adsorbate/adsorbent interactions, while the Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) model helps to distinguish between physical and chemical adsorption processes based on the mean free energy of adsorption. These models all provide insight into adsorption mechanisms—whether driven by ion exchange, pore filling, or chemical bonding—and support optimization of operational parameters [94]. 5.2. Adsorption Kinetics The pseudo-first-order kinetic model is often used for systems where physical adsorption dominates, as it assumes that the rate of occupation of adsorption sites is proportional to the number of unoccupied sites. However, many studies find the pseudo-second-order model better describes the kinetics of biochar and magnetic biochar systems, indicating chemisorption as the primary mechanism involving electron sharing or exchange between adsorbent and adsorbate [95]. The applicability of these kinetic models is typically assessed through correlation coefficients and error analysis. To further investigate the adsorption mechanism, models such as the intra-particle diffusion model are employed to determine whether pore diffusion or boundary layer diffusion is the rate-limiting step. Similarly, the Elovich model is helpful for systems with heterogeneous surfaces and where adsorption activation energy varies during the process [96]. Together, these isotherm and kinetic models offer a comprehensive understanding of how pollutants such as dyes or heavy metals are removed from wastewater using magnetic or non-magnetic biochar. They guide the scaling-up of laboratory findings to real-world applications by predicting performance under various conditions. More importantly, validating these models helps researchers and engineers in optimizing adsorbent dosage, contact time, pH, and temperature to achieve cost-effective and sustainable water purification solutions. Hence, incorporating and verifying both isotherm and kinetic modelling is not only scientifically significant but also crucial for advancing practical applications in environmental remediation [97]. Table 5 presents a comparative review of the removal efficiency of biochar and its magnetic counterpart prepared from various biomass sources. Comparison review of the removal efficiency of biochar and its magnetic biochar prepared from various biomass. The Comparison of magnetic and non-magnetic biochars derived from various biomass sources reveals a significant enhancement in pollutant removal efficiency upon magnetization. Rice husk biochar demonstrated an increase in Crystal Violet removal from approximately 50% to over 90% under conditions of pH 6, 40 °C, a dosage of 0.5 g/100 mL, and 60 minutes of contact time [98]. Similarly, coconut shell biochar showed improved Acid Orange removal from ~60% to >95% at pH 3, 30 °C, and 1 g/100 mL dosage over 90 min [99]. Chicken bone-based biochar improved Rhoda mine B adsorption efficiency from ~45% to 75% under pH 7, 25 °C, 0.3 g/50 mL, in 60 min [44]. Wheat straw exhibited an increase in Methylene Blue removal from approximately 70% to over 90% at pH 8, 35 °C, with a dosage of 0.5 g/100 mL, and a contact time of 120 minutes [100]. Notably, sewage sludge biochar showed minimal improvement in Methylene Blue adsorption, rising only slightly from ~54% to ~56%, under pH 6, 25 °C, 1 g/100 mL for 90 min [101]. Ruthenium hysterophorus-derived biochar displayed high efficiency, increasing Methylene Blue removal from 94% to nearly complete at 99.99%, with optimal parameters of pH 9, 30 °C, and 0.2 g/50 mL in 60 min [102]. Rice bran-based bio char’s Ni(II) removal rose from ~60% to >90% at pH 6, 40 °C, and 1 g/100 mL in 120 min [103], while bagasse showed a significant improvement in Cr(VI) removal from ~50% to >85% at pH 2, 25 °C, and 1 g/100 mL for 90 min [104]. Corn stalk biochar enhanced Pb(II) removal from approximately 65% to over 90% under conditions of pH 5, 25 °C, a dosage of 0.5 g/100 mL, and 60 minutes of contact time [105]. Water hyacinth biochar showed a substantial improvement in Methylene Blue removal from ~70% to >95% at pH 7, 30–50 °C, with 20–30 mg in 25 mL solution for 60–90 min [106]. For Cr(VI), peanut shell-based biochar improved from ~55% to >80% under pH 2, 40 °C, 1 g/100 mL, and 120 min [107], while bamboo-based biochar increased Methylene Blue removal from ~60% to >90% at pH 7, 30 °C, and 0.2 g/50 mL in 60 min [108]. Sugarcane bagasse improved Pb (II) removal from ~70% to >95% at pH 6, 25 °C, with 0.5 g/100 mL in 90 min [109]. Corn cob enhanced Ni(II) removal from ~60% to >85% at pH 5.5, 40 °C, and 0.4 g/100 mL in 90 min [110], and sawdust-based biochar increased Cd(II) adsorption from ~50% to >80% under pH 5.5, 30 °C, 1 g/100 mL, and 60 min [111]. Algal biomass biochar improved Methylene Blue removal from ~65% to >90% at pH 8, 25 °C, and 0.3 g/50 mL in 90 min [112], while fruit peel biochar enhanced Cr(VI) removal from ~55% to >85% at pH 2, 35 °C, and 0.5 g/100 mL in 120 min [113]. Wood chip biochar exhibited an increase in Pb(II) removal from approximately 60% to over 90% under continuous flow conditions at 5 mL/min, with a 5 cm bed height and pH 5 [114]. Rice straw-based biochar increased Methylene Blue removal from ~70% to >95% at pH 7, 30 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, and 60–90 min of contact [115]. Lastly, orange peel biochar enhanced Cd(II) removal from ~50% to >80% at pH 6, 25 °C, 1 g/100 mL, and 60 min [116].

Biochar Source

Activation/Modification

Target Pollutants

Pollutant Type

Adsorption Behavior/Performance

Ref.

Rice Husk

H3PO4 activation

Methylene Blue (MB), Pb2+

Cationic dye, Heavy metal

High surface area, electrostatic attraction, and pore diffusion

[82]

Water Hyacinth

Magnetic biochar (Fe3O4)

Congo Red (CR), Cr(VI)

Anionic dye, Metal ion

Good removal via electrostatic binding and redox with Fe3+/Fe2+

[83]

Coconut Shell

ZnCl2 activation

Rhodamine B, Cu2+

Cationic dye, Metal

ZnCl2 improves microporosity; adsorption via surface complexation

[84]

Corn Stover

Fe-impregnated biochar

Arsenic (As(V)), Nitrate

Metalloid, Anion

Fe provides reactive sites for ligand exchange and reduction

[85]

Banana Peel

Untreated/base-treated

Pb2+, Cd2+

Heavy metals

Surface functional groups (–OH, –COOH) aid metal ion complexation

[86]

Peanut Shell

Magnetic (Fe3O4-coated)

Methylene Blue, Cr (VI)

Dye, Metal ion

Magnetic separation + high surface binding; Fe3O4 aids reduction

[87]

Wheat Straw

KOH activation

Reactive Black 5

Anionic dye

High surface area and π–π interactions with aromatic rings

[88]

Sugarcane Bagasse

Acid treatment

Tannic acid, Zn2+

Organic acid, Metal ion

Carboxylic groups bind metals and organics; a low-cost sorbent

[89]

Sawdust

NaOH activation

Phenol, Ni2+

Organic, Metal ion

Surface oxygen functional groups enhance binding

[90]

Pine Wood

Magnetic with Fe/Co oxides

Cr (VI), Methylene Blue

Metal, Dye

Dual redox-adsorption pathways; good recyclability

[91]

S No.

Biomass Source

Pollutant

Isotherm Models

Kinetic Models

Non-Magnetic Biochar Removal Efficiency (%)

Magnetic Biochar Removal Efficiency (%)

Parameters

Ref.

1

Coconut Shell

Acid Orange

Langmuir

Pseudo-Second-Order

~60%

>95%

pH 3, 30 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 90 min contact time

[98]

2

Chicken Bones

Rhodamine B

Langmuir, Freundlich

Pseudo-First-Order

~45%

75%

pH 7, 25 °C, 0.3 g/50 mL, 60 min contact time

[99]

3

Wheat Straw

Methylene Blue

Langmuir, Temkin

Pseudo-Second-Order

~70%

>90%

pH 8, 35 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, 120 min contact time

[100]

4

Sewage Sludge

Methylene Blue

Freundlich

Elovich

~54%

~56%

pH 6, 25 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 90 min contact time

[101]

5

Parthenium hysteron phorus

Methylene Blue

Langmuir, Freundlich

Pseudo-Second-Order

94%

99.99%

pH 9, 30 °C, 0.2 g/50 mL, 60 min contact time

[102]

6

Rice Bran

Ni(II)

Langmuir

Pseudo-Second-Order

~60%

>90%

pH 6, 40 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 120 min contact time

[103]

7

Bagasse

Cr(VI)

Langmuir, Temkin

Pseudo-Second-Order

~50%

>85%

pH 2, 25 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 90 min contact time

[104]

8

Corn Stalk

Pb(II)

Langmuir, Freundlich

Intra-Particle Diffusion

~65%

>90%

pH 5, 25 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, 60 min contact time

[105]

9

Water Hyacinth

Methylene Blue

Langmuir, Freundlich

Pseudo-Second-Order

~70%

>95%

pH 7, 30–50 °C, 20–30 mg/25 mL, 60–90 min contact time

[106]

10

Peanut Shell

Cr(VI)

Langmuir, Dubinin-Radushkevich

Elovich

~55%

>80%

pH 2, 40 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 120 min contact time

[107]

11

Bamboo

Methylene Blue

Langmuir

Pseudo-Second-Order

~60%

>90%

pH 7, 30 °C, 0.2 g/50 mL, 60 min contact time

[108]

12

Sugarcane Bagasse

Pb(II)

Langmuir, Freundlich

Pseudo-First-Order

~70%

>95%

pH 6, 25 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, 90 min contact time

[109]

13

Corn Cob

Ni(II)

Freundlich

Pseudo-Second-Order

~60%

>85%

pH 5.5, 40 °C, 0.4 g/100 mL, 90 min contact time

[110]

14

Sawdust

Cd(II)

Langmuir, Temkin

Pseudo-Second-Order

~50%

>80%

pH 5.5, 30 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 60 min contact time

[111]

15

Algal Biomass

Methylene Blue

Langmuir, Freundlich

Intra-Particle Diffusion

~65%

>90%

pH 8, 25 °C, 0.3 g/50 mL, 90 min contact time

[112]

16

Fruit Peels

Cr(VI)

Freundlich

Pseudo-Second-Order

~55%

>85%

pH 2, 35 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, 120 min contact time

[113]

17

Wood Chips

Pb(II)

Langmuir

Pseudo-Second-Order

~60%

>90%

Flow rate 5 mL/min, bed height 5 cm, pH 5

[114]

18

Rice Straw

Methylene Blue

Langmuir, Freundlich

Pseudo-Second-Order

~70%

>95%

pH 7, 30 °C, 0.5 g/100 mL, 60–90 min contact time

[115]

19

Orange Peel

Cd(II)

Temkin, Freundlich

Elovich

~50%

>80%

pH 6, 25 °C, 1 g/100 mL, 60 min contact time

[116]

This allows pollutants to be physically trapped within the micropores and mesopores, a process known as pore filling. At the same time, surface complexation occurs when metal ions form coordination bonds with surface functional groups such as –COOH and –OH [117]. These interactions are often stronger and more specific than physical adsorption and lead to chemisorption [118]. Evidence of complexion can be observed through techniques like FTIR, which reveal shifts in characteristic functional group peaks following adsorption. Another important class of interactions includes π–π interactions and hydrogen bonding [119], especially relevant in the adsorption of organic pollutants with aromatic structures. The π–π interactions take place between the aromatic rings present in dye molecules and the conjugated aromatic systems in lignin or carbonized biomass surfaces [120]. Hydrogen bonding, on the other hand, involves interactions between polar functional groups on the pollutant and the biomass, particularly –OH, –NH2, and –COOH groups [121]. These interactions not only enhance adsorption capacity but also contribute to the stability of the adsorbed species on the biomass surface [122]. Figure 5 illustrates the mechanisms of pollutant removal using magnetic biochar. 6.1. Fenton-like Catalytic Degradation Potential Beyond passive adsorption, certain biomass-derived materials exhibit Fenton-like catalytic degradation properties, especially after thermal or chemical treatment. These materials may retain residual transition metals such as iron (Fe), copper (Cu), or manganese (Mn), which can activate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH). This oxidative process results in the degradation of complex organic pollutants [123]. The classical Fenton reaction involves Fe2+ reacting with H2O2 to generate •OH radicals, which then oxidize dye molecules or other contaminants into smaller, less harmful products. Such reactions provide a dual mechanism of pollutant removal—adsorption followed by chemical degradation—which enhances the overall efficiency [124]. For example, calcined water hyacinth ash, which retains iron content, has demonstrated Fenton-like activity, enabling the degradation of Methylene Blue dye beyond the levels achievable through adsorption alone. Table 6 illustrates the relationship between pollutant removal mechanisms and the corresponding adsorption kinetics. Linkage between pollutant removal mechanism and appropriate adsorption kinetics. 6.2. Synergistic Effects of Iron Nanoparticles in Pollutant Removal The incorporation of iron nanoparticles (Fe3O4) into biomass-based adsorbents introduces powerful synergistic effects in pollutant removal. These composites not only exhibit enhanced adsorption but also enable magnetic separation, facilitating easy recovery and reuse [133]. Iron nanoparticles contribute to pollutant degradation through several pathways, including reductive transformation, where zero-valent iron (Fe0) reduces contaminants like Cr (VI) to less toxic forms such as Cr (III). Additionally, in the presence of H2O2, Fe-based nanocomposites can catalyse Fenton-like reactions, as previously discussed, further breaking down dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides [134]. The synergistic effects stem from the combination of high surface area, active metal sites, and reactive oxygen species generation. These features make Fe-loaded biomass materials, such as Fe–biochar or Fe–modified water hyacinth adsorbents, highly effective and versatile platforms for treating a wide range of water pollutants [135]. 6.3. The Reusability of the Biochar Material The reuse performance of biochar as an adsorbent is influenced by several critical factors. One primary issue is the saturation of active sites, where adsorption sites become occupied by pollutants, reducing the biochar’s capacity in subsequent cycles [136]. Additionally, structural degradation can occur during repeated washing or regeneration processes—especially under high-temperature treatments or chemical exposure—which may lead to the breakdown of the biochar’s porous structure. Another key factor is the loss of surface functional groups such as –OH and –COOH, which play a crucial role in pollutant binding; these groups can be stripped away during acid or base regeneration, resulting in diminished adsorption efficiency [137]. Furthermore, incomplete desorption of previously adsorbed pollutants can block microspores or active sites, limiting the material’s effectiveness in later cycles. For magnetic biochar, particularly those based on iron (Fe), corrosion or iron leaching may occur, resulting in reduced magnetic recovery efficiency and a decline in reactive surface functionality. In terms of observable trends across reuse cycles, a noticeable decline in performance is often recorded. Between the first and second reuse cycles, an efficiency loss of about 5–15% is commonly observed [138]. This loss can increase to 10–25% by the third cycle. If regeneration is not properly optimized, biochar may experience up to 40% efficiency reduction after five cycles. These performance losses highlight the importance of understanding and mitigating the degradation mechanisms associated with biochar reuse. 6.4. Method or Approach to Demonstrate the Reusability of the Biochar Material To evaluate and demonstrate the reusability of biochar, several methods can be employed. Batch desorption–adsorption studies involve measuring the recovery of adsorption capacity by desorbing pollutants with mild agents (e.g., acid, base, or ethanol) after each cycle and reintroducing the pollutant to assess performance. Thermal regeneration tests assess the structural stability of biochar by heating it at 300–500 °C under an inert atmosphere and monitoring changes in surface area. Characterization techniques, including FTIR, XRD, and SEM, are employed before and after reuse cycles to assess changes in functional groups, surface morphology, and crystallinity [139]. For magnetic biochar, magnetic recovery tests help determine separation efficiency and magnetic strength across cycles. Additionally, leaching tests are performed to ensure environmental safety by assessing the release of metal ions (e.g., Fe, Zn) from spent biochar. A standard approach to test reusability includes running at least five adsorption–desorption cycles using a fixed biochar dose (e.g., 20 mg/25 mL) and known pollutant concentration under controlled pH and temperature conditions. Regeneration is performed using a mild desorbing agent such as 0.1 M HCl for metals or 0.1 M NaOH for dyes. Performance is evaluated through removal efficiency, desorption efficiency, and mass loss per cycle. After the final cycle, comparative characterization (BET, FTIR, SEM–EDS) is used to assess structural and chemical changes [140]. For example, adsorption efficiency may decrease from 92% in the first cycle to around 74% by the fifth, with corresponding decreases in desorption efficiency and remaining capacity. This protocol provides a comprehensive and practical framework to demonstrate the reusability and long-term efficiency of biochar-based adsorbents.![Figure 5: Mechanisms of pollutant removal using magnetic biochar (adopted from [122]).](/uploads/source/articles/sustainable-processes-connect/2025/volume1/20250012/image005.png)

Pollutant

Removal Mechanism

Best-Fit Kinetic Model

Why This Model is Appropriate

Ref.

Methylene Blue (MB)

(Cationic dye)Electrostatic attraction to negatively charged sites; pore diffusion; π–π stacking

Pseudo-second-order

Chemisorption dominates via electron sharing/exchange between the dye and surface functional groups

[125]

Congo Red (CR)

(Anionic dye)Electrostatic interaction with a positively charged surface; H-bonding

Pseudo-second-order

Involves valence forces or surface complexation, indicating chemisorption

[126]

Reactive Black 5

(Anionic dye)Electrostatic bonding and π–π interactions

Pseudo-second-order

Rate controlled by surface interactions, not just dye concentration

[127]

Pb2+ (Lead ion)

Surface complexation with –COOH/–OH; ion exchange

Pseudo-second-order

Strong interaction and possible chemical bonding with surface ligands

[128]

Cd2+ (Cadmium ion)

Ion exchange, surface complexation

Pseudo-second-order

Chemisorption is likely due to inner-sphere complexation on active sites

[129]

Cu2+ (Copper ion)

Ion exchange; precipitation on surface; coordination with O/N groups

Pseudo-second-order

Involves coordination-type adsorption—slower and more chemically controlled

[130]

Ni2+ (Nickel ion)

Complexation with surface oxygen functional groups

Pseudo-second-order

Adsorption governed by a rate-limiting chemisorption step

[131]

Cr(VI)

Electrostatic attraction; redox reaction (Cr(VI) → Cr(III))

Pseudo-second-order

Adsorption + redox (chemical transformation), fitting second-order assumptions

[132]

Despite considerable progress in the use of biomass-derived adsorbents, particularly those based on water hyacinth, several research gaps and limitations still persist. Most studies have focused on batch experiments under controlled laboratory conditions, often with synthetic dye solutions [141]. These do not always represent the complex matrices found in real industrial effluents. Furthermore, there is a lack of understanding regarding the long-term stability, desorption behavior, and regeneration capacity of these adsorbents over multiple cycles. Limited insights into the exact mechanistic pathways, particularly under variable environmental conditions such as fluctuating pH, ionic strength, and competing ions, also constrain the comprehensive application of these materials [142]. Additionally, in-depth toxicological studies on the release of any potentially harmful by-products or residual materials after treatment are still underexplored. One of the most pressing concerns is the scale-up and industrial feasibility of using water hyacinth-based or magnetic biochar materials. Although lab-scale results are promising, scaling up the production process to an industrial level presents challenges, including ensuring a consistent raw material supply, maintaining cost-effectiveness in activation or nanoparticle loading processes, and managing secondary waste streams [143]. The variability in biomass composition due to geographic, seasonal, or environmental differences may also affect reproducibility and adsorbent performance on a commercial scale. Moreover, integration into existing wastewater treatment systems requires standardized operating parameters and compliance with regulatory frameworks, which are yet to be fully addressed. In terms of future directions, there is growing interest in developing magnetic biochar composites with enhanced functionalities [144]. The advantages include easy separation using external magnetic fields, enhanced reusability, and dual functionality for both adsorption and catalytic degradation. Future research could focus on green synthesis techniques for embedding iron or other transition metal nanoparticles into biochar matrices, reducing the reliance on harsh chemicals and minimizing environmental impact. Advanced characterization techniques, such as synchrotron-based spectroscopy, electron tomography, and real-time in situ monitoring, can help elucidate the dynamic interactions between pollutants and biochar surfaces [145]. Additionally, exploring synergistic combinations with photo-catalytic or microbial systems may lead to the next generation of hybrid pollutant removal technologies.

Water hyacinth-based bioadsorbents, particularly when modified into magnetic nanocomposites, represent a sustainable and low-cost approach for addressing water pollution. Their multifaceted adsorption mechanisms, coupled with catalytic and magnetic properties, make them suitable candidates for real-world applications. However, to fully realize their potential, future research must address scale-up challenges, ensure environmental safety, and optimize performance under practical conditions. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration among material scientists, environmental engineers, and industrial stakeholders will be essential to translate laboratory innovations into field-ready solutions for sustainable wastewater treatment.

| BOD | Biological Oxygen Demand |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| MB | Methylene Blue |

| CR | Congo Red |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (surface area analysis) |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| VSM | Vibrating Sample Magnetometry |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic Acid |

| TPC | Total Phenolic Compounds |

Conceptualization, methodology, software: A.K. (Avanish Kumar); Validation, formal analysis, funding acquisition: A.K. (Ashish Kapoor); Investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration: G.L.D., A.K.R., and D.B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

The authors A.K., A.K., G.L.D., and D.B.P. are thankful to HBTU Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, for the necessary facilities.

[1] Smail, E.A.; DiGiacomo, P.M.; Seeyave, S.; Djavidnia, S.; Celliers, L.; Traon, P.Y.L.; Gault, J.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Plag, H.P.; Pequignet, C.; et al. An Introduction to the ‘Oceans and Society: Blue Planet’Initiative. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2019, 12, S1–S11. [CrossRef]

[2] Mishra, R.K. Fresh Water Availability and Its Global Challenge. Br. J. Multidiscip. Adv. Stud. 2023, 4, 1–78. [CrossRef]

[3] Shafik, W. Pathways to Climate Neutrality: Understanding Ice Cap Reduction, Glacial Melt, and Sea Level Change and Adoption. In Climate Neutrality Through Smart Eco-Innovation and Environmental Sustainability; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 53–67. [CrossRef]

[4] Lachassagne, P. What Is Groundwater? How to Manage and Protect Groundwater Resources. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 76, 17–24. [CrossRef]

[5] Pradinaud, C.; Northey, S.; Amor, B.; Bare, J.; Benini, L.; Berger, M.; Boulay, A.M.; Junqua, G.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Margni, M.; et al. Defining Freshwater as a Natural Resource: A Framework Linking Water Use to the Area of Protection Natural Resources. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 960–974. [CrossRef]

[6] Duda, A.M. Addressing Nonpoint Sources of Water Pollution Must Become an International Priority. Water Sci. Technol. 1993, 28, 1–11. [CrossRef]

[7] Kumar, P.S.; Saravanan, A. Sustainable wastewater treatments in textile sector. In Sustainable Fibres and Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 323–346. [CrossRef]

[8] Daud, M.K.; Nafees, M.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Bajwa, R.A.; Shakoor, M.B.; Arshad, M.U.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Deeba, F.; Murad, W.; et al. Drinking Water Quality Status and Contamination in Pakistan. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7908183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9] Sall, M.L.; Diaw, A.K.D.; Gningue-Sall, D.; Aaron, S.E.; Aaron, J.J. Toxic Heavy Metals: Impact on the Environment and Human Health, and Treatment with Conducting Organic Polymers, a Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29927–29942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10] Arya, R.; Garg, A.; Majumder, S. Removal of Ciprofloxacin and Amoxicillin from Wastewater Using Photocatalysis and Biological Treatment Methods: A Mini Review. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2025, 23, 755–776. [CrossRef]

[11] Sapari, N. Treatment and Reuse of Textile Wastewater by Overland Flow. Desalination 1996, 106, 179–182. [CrossRef]

[12] Ersahin, M.E.; Ozgun, H.; Dereli, R.K.; Ozturk, I.; Roest, K.; Van Lier, J.B. A Review on Dynamic Membrane Filtration: Materials, Applications and Future Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 122, 196–206. [CrossRef]

[13] Deng, Y.; Zhao, R. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 167–176. [CrossRef]

[14] Wang, G.; Dai, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15557–15578. [CrossRef]

[15] Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Chen, G. Preparation and Application of Magnetic Biochar in Water Treatment: A Critical Review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 711, 134847. [CrossRef]

[16] Kumar, D.; Pandit, P.D.; Patel, Z.; Bhairappanavar, S.B.; Das, J. Perspectives, scope, advancements, and challenges of microbial technologies treating textile industry effluents. In Microbial Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 237–260. [CrossRef]

[17] Giri, D.D.; Jha, J.; Tiwari, A.K.; Srivastava, N.; Hashem, A.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Elsayed, F.; Pal, D.B. Java Plum and Amaltash Seed Biomass Based Bio-Adsorbents for Synthetic Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 280, 116890. [CrossRef]

[18] Sakhiya, A.K.; Anand, A.; Kaushal, P. Production, Activation, and Applications of Biochar in Recent Times. Biochar 2020, 19, 253–285. [CrossRef]

[19] Liu, C.; Zhang, H. Modified-Biochar Adsorbents (MBAs) for Heavy-Metal Ions Adsorption: A Critical Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107393. [CrossRef]

[20] Malanova, N.V.; Korobochkin, V.V.; Кosintsev, V.I. The Application of Ammonium Hydroxide and Sodium Hydroxide for Reagent Softening of Water. Procedia Chem. 2014, 10, 162–167. [CrossRef]

[21] Tan, S.Q.; Ishak, S.; Lim, N.H.A.S.; Ngian, S.P.; Sasui, S.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B. Physicochemical properties of reactive MgO at different alkali precursors and calcination temperatures. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117054. [CrossRef]

[22] Iranmanesh, M.; Hulliger, J. Magnetic Separation: Its Application in Mining, Waste Purification, Medicine, Biochemistry and Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5925–5934. [CrossRef]

[23] Feng, Z.; Yuan, R.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, B.; Chen, H. Preparation of Magnetic Biochar and Its Application in Catalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants: A Review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 765, 142673. [CrossRef]

[24] Qu, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Tong, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tao, Y.; Dai, X.; et al. Applications of Functionalized Magnetic Biochar in Environmental Remediation: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 434, 128841. [CrossRef]

[25] Velusamy, S.; Roy, A.; Sundaram, S.; Mallick, T.K. A Review on Heavy Metal Ions and Containing Dyes Removal Through Graphene Oxide—Based Adsorption Strategies for Textile Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1570–1610. [CrossRef]

[26] Majetich, S.A.; Wen, T.; Booth, R.A. Functional Magnetic Nanoparticle Assemblies: Formation, Collective Behavior, and Future Directions. Acs Nano 2011, 5, 6081–6084. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[27] Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, T.; Qi, L. Microscopic Characteristics and Formation of Various Types of Organic Matter in High-Overmature Marine Shale via SEM. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1310. [CrossRef]

[28] Sinha, P.; Datar, A.; Jeong, C.; Deng, X.; Chung, Y.G.; Lin, L. Surface Area Determination of Porous Materials Using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) Method: Limitations and Improvements. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 20195–20209. [CrossRef]

[29] Qu, J.; Wang, S.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; Yin, R.; Jiang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Magnetic Porous Biochar with High Specific Surface Area Derived from Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal and Pyrolysis Treatments of Water Hyacinth for Cr (Ⅵ) and Tetracycline Adsorption from Water. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125692. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[30] Thangaraj, B.; Muthukurumban, N.; Chelliah, P.; Rethnamuthu, S.D. Synthesize of Tri-Metal Oxide MnO2-ZnO-CeO2 Nanocomposites via Co-Precipitation Technique for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 1–31. [CrossRef]

[31] Stolarczyk, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Brougham, D.F. Controlled Growth of Nanoparticle Clusters Through Competitive Stabilizer Desorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009, 48, 175–178. [CrossRef]

[32] Martínez, C.E.; McBride, M.B. Solubility of Cd2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+ in Aged Coprecipitates with Amorphous Iron Hydroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 743–748. [CrossRef]

[33] Leng, L.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Huang, H. An Overview on Engineering the Surface Area and Porosity of Biochar. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 763, 144204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[34] Nnadozie, E.C.; Ajibade, P.A. Preparation, Phase Analysis and Electrochemistry of Magnetite (Fe3O4) and Maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) Nanoparticles. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 22124. [CrossRef]

[35] Song, Q.; Zhao, H.; Jia, J.; Yang, L.; Lv, W.; Bao, J.; Shu, X.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, P. Pyrolysis of Municipal Solid Waste with Iron-Based Additives: A Study on the Kinetic, Product Distribution and Catalytic Mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120682. [CrossRef]

[36] Barzallo, M.F.; Solís, Y.E.; Madera, D.; Díaz, A.M. Preparation and Characterization of Unactivated, Activated, and γ-Fe2O3 Nanoparticle-Functionalized Biochar from Rice Husk via Pyrolysis for Dyes Removal in Aqueous Samples. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 30. [CrossRef]

[37] Nguyen, T.A.H.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Pham, T.D. One-Step Preparation of Rice Husk-Based Magnetic Biochar and Its Catalytic Activity for p-Nitrophenol Degradation. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 78, 379–384. [CrossRef]

[38] Sashidhar, P.; Yakkala, K.; Bhunia, R.K.; Patowary, S.; Kochar, M.; Mandal, S.; Brau, L.; Cahill, D.; Dubey, M. Nano-Biochar Supported Zn Delivery in Plants to Enhance Seedling Growth and ROS Management in Rice. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 3791–3807. [CrossRef]

[39] Zhang, D.; He, H.; Gao, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y. Effects of Pretreatment and FeCl3 Preload of Rice Husk on Synthesis of Magnetic Carbon Composites by Pyrolysis for Supercapacitor Application. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 136, 219–228. [CrossRef]

[40] Zghari, B.; Doumenq, P.; Romane, A.; Boukir, A. GC-MS, FTIR and 1H, 13C NMR Structural Analysis and Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Olive Mill Wastewater Extracted from Oued Oussefrou Effluent (Beni Mellal-Morocco). J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 4496–4509. [CrossRef]

[41] Sarkar, S.; Dey, K. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Characterization of Some Transition metal Complexes of a New Hexadentate N2S2O2 Schiff Base Ligand. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2005, 62, 383–393. [CrossRef]

[42] Shang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dong, J.; Yao, M.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhai, C.; Shen, F.; Hou, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Ultrahard Bulk Amorphous Carbon from Collapsed Fullerene. Nature 2021, 599, 599–604. [CrossRef]

[43] Thines, K.R.; Abdullah, E.C.; Mubarak, N.M.; Ruthiraan, M. Synthesis of Magnetic Biochar from Agricultural Waste Biomass to Enhancing Route for Waste Water and Polymer Application: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 257–276. [CrossRef]

[44] Kopac, T.; Lin, S.D. A Review on the Characterization of Microwave-Induced Biowaste-Derived Activated Carbons for Dye Adsorption. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 8717–8748. [CrossRef]

[45] Li, H.; Dong, X.; Da Silva, E.B.; De Oliveira, L.M.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.Q. Mechanisms of Metal Sorption by Biochars: Biochar Characteristics and Modifications. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 466–478. [CrossRef]

[46] Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, S. Adsorption Characteristics of Modified Bamboo Charcoal on Cu (II) and Cd (II) in Water. Toxics 2022, 10, 787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[47] Kefirov, R.; Ivanova, E.; Hadjiivanov, K.; Dźwigaj, S.; Che, M. FTIR Characterization of Fe3+–OH Groups in Fe–H–BEA Zeolite: Interaction with CO and NO. Catal. Lett. 2008, 125, 209–214. [CrossRef]

[48] Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [CrossRef]

[49] Zhou, Y.; Gao, B.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Fang, J.; Sun, Y.; Cao, X. Sorption of Heavy Metals on Chitosan-modified Biochars and Its Biological Effects. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 231, 512–518. [CrossRef]

[50] Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Lin, Z.; Chai, L. Selective Tl (I) Removal by Prussian Blue–Zero Valent Iron Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 24368–24376. [CrossRef]

[51] Periyasamy, A.P. Recent Advances in the Remediation of Textile-Dye-Containing Wastewater: Prioritizing Human Health and Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 495. [CrossRef]

[52] Katibi, K.K.; Shitu, I.G.; Yunos, K.F.M.; Azis, R.S.; Iwar, R.T.; Adamu, S.B.; Umar, A.M.; Adebayo, K.R. Unlocking the Potential of Magnetic Biochar in Wastewater Purification: A Review on the Removal of Bisphenol A from Aqueous Solution. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1–38. [CrossRef]

[53] Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Adsorptive Removal of Antibiotics from Water and Wastewater: Progress and Challenges. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015, 532, 112–126. [CrossRef]

[54] Sivaraj, R.; Namasivayam, C.; Kadirvelu, K. Orange Peel as an Adsorbent in the Removal of Acid Violet 17 (Acid Dye) from Aqueous Solutions. Waste Manag. 2001, 21, 105–110. [CrossRef]

[55] Lwin, C.S.; Kim, Y.N.; Lee, M.; Jung, H.I.; Kim, K.R. In Situ Immobilization of Potentially Toxic Elements in Arable Soil by Adding Soil Amendments and the Best Ways to Maximize Their Use Efficiency. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 115–134. [CrossRef]

[56] Fang, Q.; Chen, B.; Lin, Y.; Guan, Y. Aromatic and Hydrophobic Surfaces of Wood-Derived Biochar Enhance Perchlorate Adsorption via Hydrogen Bonding to Oxygen-Containing Organic Groups. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 279–288. [CrossRef]

[57] Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Shah, S.M.; Su, X. Adsorption and Removal of Tetracycline Antibiotics from Aqueous Solution by Graphene Oxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 368, 540–546. [CrossRef]

[58] Zeidan, H.; Erunal, E.; Marti, M.E. Synthesis of CeO2@ SiO2 Nanocomposites for Adsorption of Cu (II) and Pb (II): Insights from Batch and Column Studies. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 1–22. [CrossRef]

[59] Adewuyi, A. Chemically Modified Biosorbents and Their Role in the Removal of Emerging Pharmaceutical Waste in the Water System. Water 2020, 12, 1551. [CrossRef]

[60] Li, Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. Characterization of Modified Biochars Derived from Bamboo Pyrolysis and Their Utilization for Target Component (Furfural) Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 5119–5127. [CrossRef]

[61] Bediako, J.K.; Lin, S.; Sarkar, A.K.; Zhao, Y.; Choi, J.W.; Song, M.H.; Cho, C.W.; Yun, Y.S. Evaluation of Orange Peel-Derived Activated Carbons for Treatment of Dye-Contaminated Wastewater Tailings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1053–1068. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[62] Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Pazos, M.; Rosales, E.; Sanromán, M.A. Unravelling the Environmental Application of Biochar as Low-Cost Biosorbent: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7810. [CrossRef]

[63] Cai, T.; Du, H.; Liu, X.; Tie, B.; Zeng, Z. Insights into the Removal of Cd and Pb from Aqueous Solutions by NaOH–EtOH-Modified Biochar. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102031. [CrossRef]

[64] Mehta, C.M.; Khunjar, W.O.; Nguyen, V.; Tait, S.; Batstone, D.J. Technologies to Recover Nutrients from Waste Streams: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 45, 385–427. [CrossRef]

[65] Phaenark, C.; Jantrasakul, T.; Paejaroen, P.; Chunchob, S.; Sawangproh, W. Sugarcane Bagasse and Corn Stalk Biomass as a Potential Sorbent for the Removal of Pb (II) and Cd (II) from Aqueous Solutions. Trends Sci. 2022, 20, 6221. [CrossRef]

[66] Reynel-Ávila, H.E.; Camacho-Aguilar, K.I.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Mendoza-Castillo, D.I.; González-Ponce, H.A.; Trejo-Valencia, R. Engineered Magnetic Carbon-Based Adsorbents for the Removal of Water Priority Pollutants: An Overview. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2021, 9917444. [CrossRef]

[67] Enaime, G.; Baçaoui, A.; Yaacoubi, A.; Lübken, M. Biochar for Wastewater Treatment—Conversion Technologies and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3492. [CrossRef]

[68] Liang, M.; Lu, L.; He, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y. Applications of Biochar and Modified Biochar in Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil: A Descriptive Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14041. [CrossRef]

[69] Yuan, J.H.; Xu, R.K.; Zhang, H. The Forms of Alkalis in the Biochar Produced from Crop Residues at Different Temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3488–3497. [CrossRef]

[70] Ndoun, M.C.; Elliott, H.A.; Preisendanz, H.E.; Williams, C.F.; Knopf, A.; Watson, J.E. Adsorption of Pharmaceuticals from Aqueous Solutions Using Biochar Derived from Cotton Gin Waste and Guayule Bagasse. Biochar 2021, 3, 89–104. [CrossRef]

[71] Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; He, L.; Lu, K.; Sarmah, A.; Li, J.; Bolan, N.S.; Pei, J.; Huang, H. Using Biochar for Remediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals and Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8472–8483. [CrossRef]

[72] Akinhanmi, T.F.; Ofudje, E.A.; Adeogun, A.I.; Aina, P.; Joseph, I.M. Orange Peel as Low-Cost Adsorbent in the Elimination of Cd (II) Ion: Kinetics, Isotherm, Thermodynamic and Optimization Evaluations. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2020, 7, 1–16. [CrossRef]

[73] Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Sánchez-Albores, R.M.; Escorcia-García, J.; Cruz-Salomón, A.; Bartolo-Pérez, P.; Adhikari, A.; Hernández-Cruz, M.D.C.; Torres-Ventura, H.H.; Esquinca-Avilés, H.A. Green Synthesis of CaO-Fe3O4 Composites for Photocatalytic Degradation and Adsorption of Synthetic Dyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 9901–9925. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[74] Gopinath, K.P.; Rajagopal, M.; Krishnan, A.; Sreerama, S.K. A Review on Recent Trends in Nanomaterials and Nanocomposites for Environmental Applications. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2021, 17, 202–243. [CrossRef]

[75] Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, R. Relative Distribution of Pb2+ Sorption Mechanisms by Sludge-Derived Biochar. Water Res. 2012, 46, 854–862. [CrossRef]

[76] Chen, B.; Chen, Z.; Lv, S. A Novel Magnetic Biochar Efficiently Sorbs Organic Pollutants and Phosphate. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 716–723. [CrossRef]

[77] Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U.; Bricka, M.; Smith, F.; Yancey, B.; Mohammad, J.; Steele, P.H.; Alexandre-Franco, M.F.; Gómez-Serrano, V.; Gong, H. Sorption of Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead by Chars Produced from Fast Pyrolysis of Wood and Bark During Bio-Oil Production. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 310, 57–73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[78] Tran, H.N.; Wang, Y.F.; You, S.J.; Chao, H.P. Insights into the Mechanism of Cationic Dye Adsorption on Activated Charcoal: The Importance of–Interactions. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 107, 168–180. [CrossRef]

[79] Yao, Y.; Gao, B.; Inyang, M.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Cao, X.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Yang, L. Removal of Phosphate from Aqueous Solution by Biochar Derived from Anaerobically Digested Sugar Beet Tailings. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190, 501–507. [CrossRef]

[80] Srivatsav, P.; Bhargav, B.S.; Shanmugasundaram, V.; Arun, J.; Gopinath, K.P.; Bhatnagar, A. Biochar as an Eco-Friendly and Economical Adsorbent for the Removal of Colorants (Dyes) from Aqueous Environment: A Review. Water 2020, 12, 3561. [CrossRef]

[81] Akhtar, M.S.; Ali, S.; Zaman, W. Innovative Adsorbents for Pollutant Removal: Exploring the Latest Research and Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 4317. [CrossRef]

[82] Srivastava, N.; Mohammad, A.; Pal, D.B.; Srivastava, M.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Singh, R.; Mishra, P.K.; Yoon, T.; Gupta, V.K. Enhancement of Fungal Cellulase Production Using Pretreated Orange Peel Waste and Its Application in Improved Bioconversion of Rice Husk Under the Influence of Nickel Cobaltite Nanoparticles. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 6687–6696. [CrossRef]

[83] Chu, T.T.H.; Nguyen, M.V. Improved Cr (VI) Adsorption Performance in Wastewater and Groundwater by Synthesized Magnetic Adsorbent Derived from Fe3O4 Loaded corn Straw Biochar. Environ. Res. 2022, 216, 114764. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[84] Yağmur, H.K.; Kaya, İ. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetic ZnCl2-Activated Carbon Produced from Coconut Shell for the Adsorption of Methylene Blue. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1232, 130071. [CrossRef]

[85] Mohan, D.; Kumar, H.; Sarswat, A.; Alexandre-Franco, M.; Pittman, C.U. Cadmium and Lead Remediation Using Magnetic Oak Wood and Oak Bark Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Chars. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 236, 513–528. [CrossRef]

[86] Annadurai, G.; Juang, R.S.; Lee, D.J. Adsorption of Heavy Metals from Water Using Banana and Orange Peels. Water Sci. Technol. 2003, 47, 185–190. [CrossRef]

[87] Soares, S.F.; Brenheiro, J.; Fateixa, S.; Daniel-Da-Silva, A.L.; Trindade, T. Multifunctional Bionanocomposites for Trace Detection of Water Contaminants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 700, 138587. [CrossRef]

[88] Yang, K.; Zhu, L.; Yang, J.; Lin, D. Adsorption and Correlations of Selected Aromatic Compounds on a KOH-Activated Carbon with Large Surface Area. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 618, 1677–1684. [CrossRef]

[89] Babel, S. Low-Cost Adsorbents for Heavy Metals Uptake from Contaminated Water: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 97, 219–243. [CrossRef]

[90] Ahmad, A.A.; Hameed, B.H.; Aziz, N. Adsorption of Direct Dye on Palm Ash: Kinetic and Equilibrium Modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 70–76. [CrossRef]

[91] Esmaeili, H.; Tamjidi, S.; Abed, M. Removal of Cu (II), Co (II) and Pb (II) from Synthetic and Real Wastewater Using Calcified Solamen Vaillanti Snail Shell. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 174, 324–335. [CrossRef]

[92] Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [CrossRef]

[93] Rajahmundry, G.K.; Garlapati, C.; Kumar, P.S.; Alwi, R.S.; Vo, D.V.N. Statistical Analysis of Adsorption Isotherm Models and Its Appropriate Selection. Chemosphere 2021, 276, 130176. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[94] Biftu, W.K.; Ravulapalli, S.; Kunta, R. Effective De-Fluoridation of Water Using Leucaena Luecocephala Active Carbon as Adsorbent. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 14, 415–426. [CrossRef]

[95] Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-Second Order Model for Sorption Processes. Process. Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [CrossRef]

[96] Chien, S.H.; Clayton, W.R. Application of Elovich Equation to the Kinetics of Phosphate Release and Sorption in Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 265–268. [CrossRef]

[97] Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherm Models of Heavy Metals by Various Adsorbents: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1837–1865. [CrossRef]

[98] Siriweera, B.; Jayathilake, S. Modifications of Coconut Waste as an Adsorbent for the Removal of Heavy Metals and Dyes from Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 10, 329–349. [CrossRef]

[99] Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U. Arsenic Removal from Water/Wastewater Using Adsorbents—A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 1–53. [CrossRef]

[100] Sodkouieh, S.M.; Kalantari, M.; Shamspur, T. Methylene Blue Adsorption by Wheat Straw-Based Adsorbents: Study of Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherms. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 873–881. [CrossRef]

[101] Inyang, M.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Cao, X. Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution by Biochars Derived from Anaerobically Digested Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 50–56. [CrossRef]

[102] Pathania, D.; Sharma, S.; Singh, P. Removal of Methylene Blue by Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Developed from Ficus Carica Bast. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S1445–S1451. [CrossRef]

[103] Demirbas, A. Heavy Metal Adsorption onto Agro-Based Waste Materials: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 220–229. [CrossRef]

[104] Babel, S.; Kurniawan, T.A. Cr(VI) Removal from Synthetic Wastewater Using Coconut Shell Charcoal and Commercial Activated Carbon Modified with Oxidizing Agents and/or Chitosan. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 951–967. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[105] Yan, S.; Yu, W.; Yang, T.; Li, Q.; Guo, J. The Adsorption of Corn Stalk Biochar for Pb and Cd: Preparation, Characterization, and Batch Adsorption Study. Separations 2022, 9, 22. [CrossRef]

[106] Kumar, A.; Devnani, G.L.; Pal, D.B. Water Hyacinth Stem-Based Bioadsorbent for Dye Removal from Synthetic Wastewater: Adsorption Kinetic Study. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 1–19. [CrossRef]

[107] Kumar, A.; Devnani, G.L.; Pal, D.B. Thermal Kinetic Analysis and Characterization of Water Hyacinth Biomass for Renewable energy application. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 1–14. [CrossRef]

[108] Hameed, B.; Din, A.; Ahmad, A. Adsorption of Methylene Blue onto Bamboo-Based Activated Carbon: Kinetics and Equilibrium Studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 819–825. [CrossRef]

[109] Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. A two-Stage Batch Sorption Optimized Design for Dye Removal to Minimize Contact Time. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 1998, 76, 313–318. [CrossRef]

[110] Emiral, H.; Demiral, İ.; Karabacakoğlu, B.; Tümsek, F. Adsorption of Ni(II) from Aqueous Solution by Activated Carbon Prepared from Almond Husk. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 144, 188–196. [CrossRef]

[111] Sulaymon, A.H.; Ebrahim, S.E.; Al–Musawi, T.J.; Abdullah, S.M. Removal of Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury Ions Using Biosorption. Iraqi J. Chem. Pet. Eng. 2010, 249, 343–351. [CrossRef]

[112] Vijayaraghavan, K.; Padmesh, T.; Palanivelu, K.; Velan, M. Biosorption of Nickel(II) Ions onto Sargassum Wightii: Application of Two-Parameter and Three-Parameter Isotherm Models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 133, 304–308. [CrossRef]

[113] Karthikeyan, G.; Anbalagan, K.; Andal, N.M. Adsorption Dynamics and Equilibrium Studies of Zn(II) onto Chitosan. J. Chem. Sci. 2004, 117, 663–672. [CrossRef]

[114] Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Sorption of Dyes and Copper Ions onto Biosorbents. Process. Biochem. 2003, 38, 1047–1061. [CrossRef]

[115] Wang, S.; Zhu, Z. Characterisation and Environmental Application of an Australian Natural Zeolite for Basic Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 946–952. [CrossRef]