APA Style

Oscar Simplice Wamba Fotsop, Pierre Fils Rodrigue Magwell, Carlos Loubadoum, Kennedy Tchoffo Djoudjeu, Pascaline Laure Nyabeu Ngnikeu, Belise Gladyce Nangueu, Claude Simo, Emile Minyaka, Léopold Gustave Lehman. (2025). Enhanced Biomass and Photosynthetic Pigment Productivity of Spirulina platensis Using a Sustainable Medium from Chicken Feather and Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0009). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.156377MLA Style

Oscar Simplice Wamba Fotsop, Pierre Fils Rodrigue Magwell, Carlos Loubadoum, Kennedy Tchoffo Djoudjeu, Pascaline Laure Nyabeu Ngnikeu, Belise Gladyce Nangueu, Claude Simo, Emile Minyaka, Léopold Gustave Lehman. "Enhanced Biomass and Photosynthetic Pigment Productivity of Spirulina platensis Using a Sustainable Medium from Chicken Feather and Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0009, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.156377.Chicago Style

Oscar Simplice Wamba Fotsop, Pierre Fils Rodrigue Magwell, Carlos Loubadoum, Kennedy Tchoffo Djoudjeu, Pascaline Laure Nyabeu Ngnikeu, Belise Gladyce Nangueu, Claude Simo, Emile Minyaka, Léopold Gustave Lehman. 2025. "Enhanced Biomass and Photosynthetic Pigment Productivity of Spirulina platensis Using a Sustainable Medium from Chicken Feather and Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0009. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.156377.

ACCESS

Research Article

ACCESS

Research Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0009

Oscar Simplice Wamba Fotsop

sfotsop@yahoo.fr

Pierre Fils Rodrigue Magwell

pierre.magwell@irad.cm

Carlos Loubadoum

loubadoumngaryom@gmail.com

Kennedy Tchoffo Djoudjeu

kennedytchoffo@gmail.com

Pascaline Laure Nyabeu Ngnikeu

pascalinelaurenyabeu@gmail.com

Belise Gladyce Nangueu

nangueubelise@gmail.com

Claude Simo

simoclaude236@gmail.com

Emile Minyaka

minyakae@yahoo.fr

Léopold Gustave Lehman

leopoldlehman@gmail.com

1 Laboratory of Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P.O. Box 24157 Douala, Cameroon

2 Biochemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P.O. Box 24157 Douala, Cameroon

3 Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, Nko’olong Station, P.O. Box 219, Kribi, Cameroon

4 Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, Specialized Research Station in Marine Ecosystems, P.O. Box 219 Kribi, Cameroon

5 Laboratory of Animal Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P.O. Box 24157 Douala, Cameroon

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 09 Apr 2025 Accepted: 08 Aug 2025 Available Online: 09 Aug 2025 Published: 11 Oct 2025

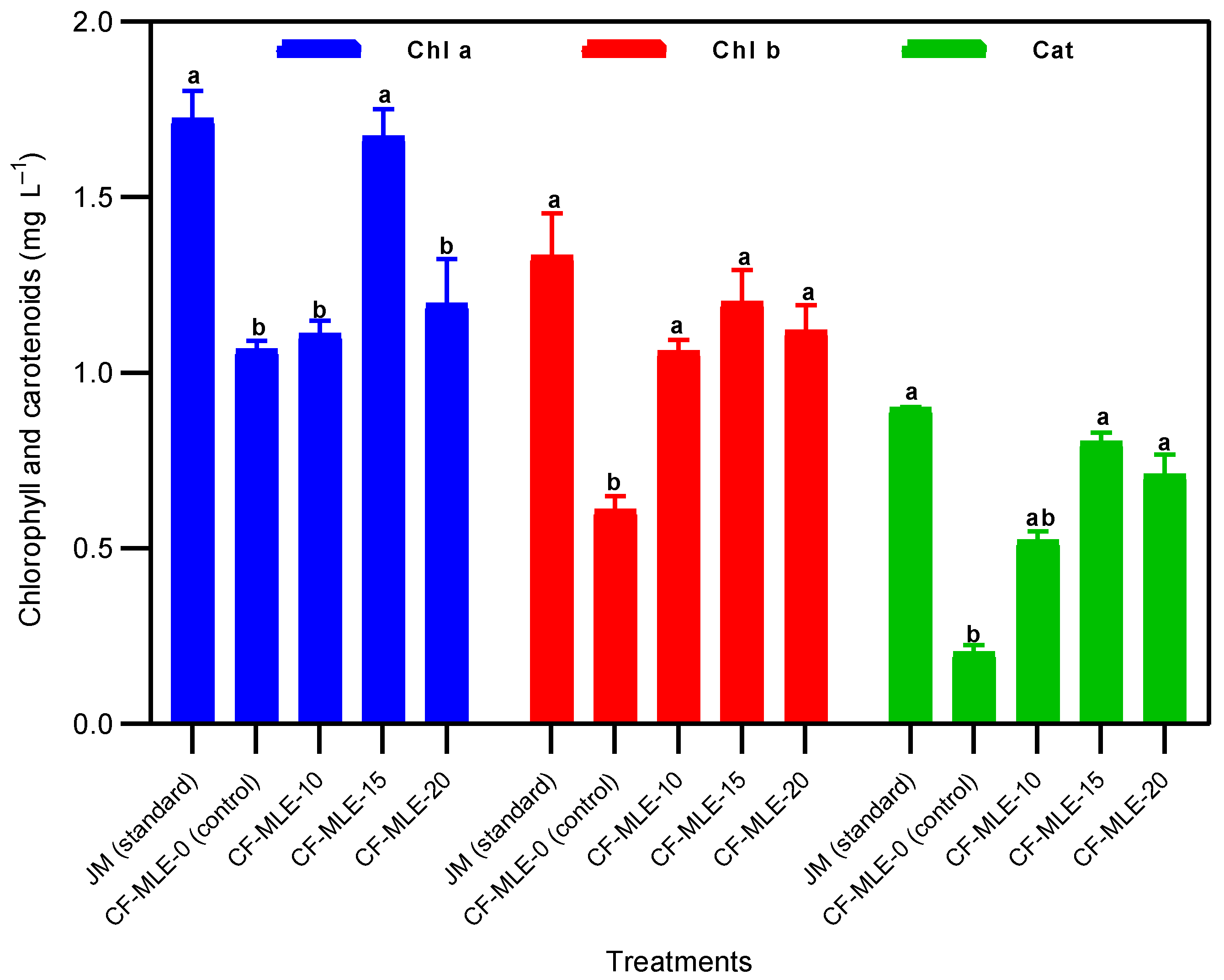

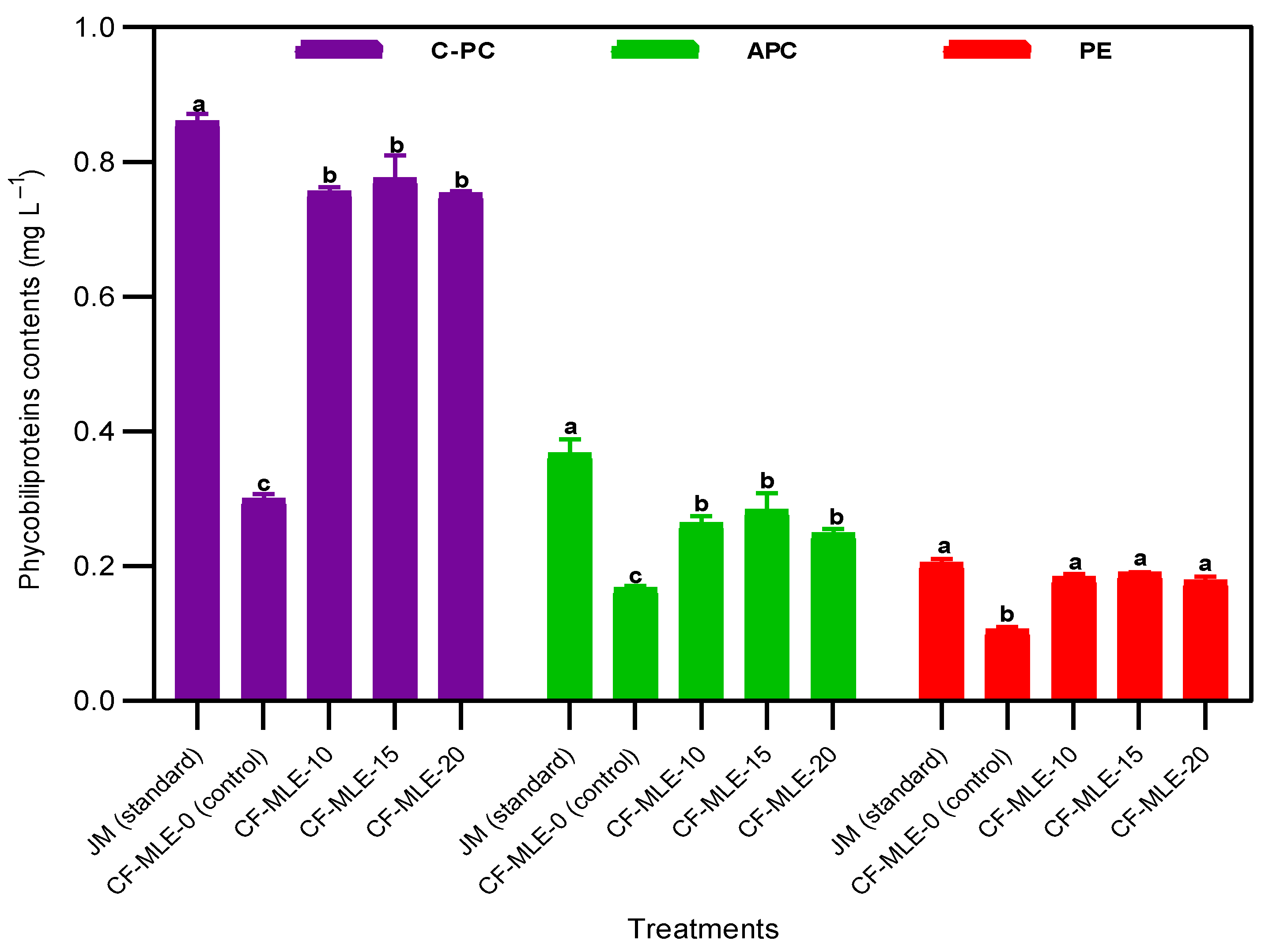

Spirulina platensis biomass represents a renewable resource for the sustainable production of high-quality products. However, substantial costs and nutrient availability limit large-scale production. Nutrients from agro-industrial by-products can serve as supplementary sources to enhance S. platensis production. This study evaluated chicken feather (CF) medium and Moringa oleifera leaf extract (MLE) as eco-friendly alternative culture media for increasing Spirulina platensis biomass and photosynthetic pigment production. The culture medium was formulated by processing chicken feathers to produce a CF-based medium. Different MLE concentrations (0, 10, 15, and 20 g L−1) were subsequently prepared in distilled water. S. platensis was cultured in cylindrical vessels under greenhouse conditions for 27 days. The CF media enriched with 15 g L−1 M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE-15) presented the highest optical density (1.68 ± 0.03) and dry-biomass concentration (1.98 ± 0.05 g L−1), outperforming the values observed in the standard (JM) and the control (CF-MLE-0) media. Moreover, the content and productivity of carotenoids and chlorophyll a were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the CF-MLE-15 treatment than in the other CF-MLE and control treatments. Nonetheless, the contents of chlorophyll a (1.72 ± 0.12 mg L−1), carotenoids (0.90 ± 0.003 mg L−1), and phycobiliproteins in the standard medium (JM) exceeded those found in the CF-MLE treatments. Consequently, a CF medium supplemented with 15 g L−1 of M. oleifera leaf extract may be a viable and economical alternative for producing S. platensis biomass and photosynthetic molecules.

Chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf extract as an eco-friendly and alternative medium for Spirulina platensis biomass and photosynthetic pigment production Chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf extract enhance Spirulina platensis growth, protein content, and photosynthetic pigment production Adequate ratio of chicken feathers to Moringa oleifera leaf extract leads to optimal Spirulina platensis biomass, protein, and photosynthetic pigment production Chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf extract provide a sustainable, cost-effective culture medium for Spirulina platensis, addressing agro-industrial waste challenges

Microalgae have attracted significant global attention due to their potential applications across diverse sectors, including renewable energy, pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, food production, and cosmetics [1]. Microalgae biomass is a renewable and cost-effective source of bioactive photosynthetic pigments [2]. Spirulina platensis (S. platensis), a blue-green, filamentous, photosynthetic cyanobacterium, is recognized as a highly promising species that thrives in aquatic habitats such as lakes, rivers, and oceans [3]. S. platensis is particularly noteworthy for its high nutritional value and therapeutic properties. S. platensis contains a high percentage of protein (50–70%), polyunsaturated fatty acids (α-linolenic acid, γ-linolenic acid), photosynthetic molecules (chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins), vitamins (provitamins A, vitamin B1), and minerals (iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc, and potassium) [4,5]. The Food and Agriculture Organization recognizes S. platensis as a vital food resource for the 21st century [6]. S. platensis has therapeutic properties, including anti-aging, anti-cancer, immunomodulatory, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects [7,8]. S. platensis is highly adaptable and can thrive under various nutritional conditions [9]. S. platensis typically uses Jourdan and Zarrouk media as nutrient sources. These two inorganic media are complex, expensive, and not widely available [10]. To reduce the production costs of S. platensis, researchers are exploring more cost-effective and readily available alternative culture media [11,12,13]. Studies have investigated the use of agro-industrial by-products, such as chicken feathers and M. oleifera leaves, as potential sources of nutrition for microalgae cultivation [14,15]. M. oleifera leaves contain vitamins and essential micronutrients such as magnesium, potassium, iron, and copper, which are necessary for microalgal growth [16,17]. Chicken feathers are a cost-effective, nutrient-rich source of nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium for microalgae cultivation [18,19]. The complementary nutrient profiles of these two agro-industrial by-products synergistically enhance microbial metabolic activity and stimulate biomass production [20,21]. Despite their inherent nutrient richness, no prior study has investigated the potential of chicken feathers and M. oleifera leaf extracts as an alternative medium for S. platensis biomass and photosynthetic pigment production. The novelty of this study lies in the use of agro-industrial by-products, such as chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaves, as prospective substrates for cultivating microalgae, including Spirulina platensis. The strategy helps mitigate production costs and alleviates challenges in agro-industrial waste management. The use of chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf extract in microalgae cultivation also provides an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic media. Thus, the current study investigated the potential of chicken feathers and M. oleifera leaf extracts as an eco-friendly alternative medium for producing S. platensis biomass and photosynthetic pigments. These findings highlight the promising use of these alternative media for producing S. platensis biomass and photosynthetic pigments.

2.1. Preparation of Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract The chicken feathers were collected from a slaughterhouse in Douala, Cameroon. The samples were washed at 50 °C in 0.5% v/v H2O2 to remove residues of blood, feces, fat, offal, and sand. The washed chicken feathers were then rinsed and dried at 105 °C for 24 h. Once dried, the barbs were manually separated from the shaft and carbonized at 440 °C for 10 min in a muffle furnace to obtain ash [22]. Subsequently, 10 g of ash was dispersed in 100 mL of distilled water (1:10 w/v) and left to stand for 24 h to create a homogenate of chicken feathers. After the homogenization process, the mixture was passed through the Whatman No. 2 filter paper. The filtrate collected was used as chicken feather medium (CF). Fresh M. oleifera leaves were harvested at the SAGRIC farm in Douala, Cameroon. The leaves were cleaned, and different quantities (20 g, 30 g, and 40 g) were mixed with 1 L of distilled water for 7 days under agitation using a homogenizer [15]. The suspension was subsequently filtered through sterile muslin cloth and Whatman No. 1 filter paper to eliminate solid particles. The filtrates obtained were diluted with an additional 1 L of distilled water to achieve final concentrations of 10, 15, and 20 g L−1 Moringa oleifera leaf extracts and sterilized at 121 °C for 30 min. The obtained extracts were used as the M. oleifera leaf extract (MLE). 2.2. Microalgae and Inoculum Culture Conditions The strain of S. platensis used in the experiments was harvested from the algal culture collection of the SAGRIC farm in Douala, Cameroon. To produce the inoculum, the S. platensis strain was cultured in Jourdan’s medium, which contained per liter: NaHCO3 (8 g), NaCl (5 g), KNO3 (2 g), MgSO4 (0.16 g), (NH4)2HPO4 (0.12 g), (NH2)2CO (0.05 g), FeSO4 (0.02 g), and CaCl2 (0.02 g). The culture of the inoculum was maintained at 28 ± 0.5 °C, under alkaline conditions (pH = 9.0 ± 0.4) in a greenhouse with white LED tube lamps (200 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and constant aeration supplied by a membrane pump (Laboport KNF, Freiburg, Germany). 2.3. Experimental Design The study used a systematic methodology, wherein S. platensis was cultivated in chicken feather medium (CF). Culture media were prepared by supplementing CF medium with 0, 10, 15, or 20 g L−1 of MLE for CF-MLE-0 (control), CF-MLE-10, CF-MLE-15, or CF-MLE-20, respectively. Jourdan’s medium served as the established standard medium (Table 1). The microalgae S. platensis was grown in 20 L cylindrical vessels set in a greenhouse maintained at 28 ± 0.5 °C, under white LED illumination (200 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and continuous aeration supplied by a membrane pump. A 10% inoculum (Inoculation volume/Medium volume) was used at the beginning of the cultivation experiment. The salinity and the pH were adjusted to 11.4 ± 0.5 PSU with NaCl and 9.0 ± 0.4 with 2 N NaOH, respectively. The trials were conducted in triplicate over the 27-day experimental period. The chemical compound of the chicken feathers medium supplemented with M. oleifera leaf extract and Jourdan medium was employed for the production of Spirulina platensis biomass. * Note: CF (chicken feathers medium), MLE (M. oleifera leaf extract). NaHCO3 and NaCl were added in all the treatments of the M. oleifera leaf extract. 2.4. Estimation of the Eco-Friendly Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract The expense associated with chicken feather medium enriched with Moringa oleifera leaf extract was calculated by taking into account the concentration and cost of every substance employed in the production of 1 kg of the material. Taxes, energy consumption, and transportation costs were excluded from the analysis. The prices for all the chemicals utilized were sourced from previous research reported by Magwell et al. [23] (Table 2). Estimation of the expenditure of the eco-friendly chicken feathers medium supplemented with Moringa oleifera leaf extract and Jourdan standard medium employed for the production of Spirulina platensis biomass. * Note: The chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf used to prepare CF (chicken feathers medium) and MLE (Moringa oleifera leaf extract), respectively, were freely collected as waste from a slaughterhouse and the SAGRIC farm in Douala, Cameroon. 2.5. Biomass and Growth Rate Assessment S. platensis samples were collected every 3 days to evaluate the dry biomass and cell optical density. The optical density of the cells was measured at 680 nm via a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (UV-VIS Spectrophotometer BK-S380, Shandong, China). Dry biomass determination was performed by filtering 20 mL samples through 47 mm GF/C glass fiber filters (X1, g). The cells within the filters were rinsed twice with distilled water, oven-dried at 50 °C for 24 h, and subsequently weighed (X2, g). The dry biomass was calculated per Equation (1): The biomass productivity (Px) and growth rate (μ) of S. platensis were determined from Equations (2) and (3), respectively: X0 and Xf represent the dry biomass at the initiation and termination of the cultivation process (t), respectively. Upon completion of the exponential growth phase (21 days), S. platensis samples were collected to assess protein, cysteine, and pigment contents. 2.6. Biochemical Analysis 2.6.1. Photosynthetic Pigments Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents Chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids were isolated from S. platensis biomass (2 mg) by adding 1 mL of 90% acetone in the absence of light for 24 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation for 15 min at 5000 rpm (Sigma 1-15K, Osterode am Harz, Germany), the supernatant was harvested from each sample. The absorbances of chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids were measured at 662 nm, 645 nm, and 470 nm, respectively. The contents of chlorophyll and carotenoids were assessed using the extinction coefficient in acetone and calculated from Equations (4)–(6) [24]. where Chl a is chlorophyll a, OD662 denotes the optical density at 662 nm, and OD645 indicates the optical density at 645 nm. where Chl b is chlorophyll b, OD645 denotes the optical density at 645 nm, and OD662 signifies the optical density at 662 nm. where OD470 represents the optical density measured at 470 nm, Chl a denotes chlorophyll a, and Chl b is chlorophyll b. Phycobiliproteins Contents The fresh S. platensis biomass was mixed with phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 6.7) at a ratio of 1:3 (w/v) through three successive freeze–thaw cycles over 24 hat 4 °C, in the dark. Subsequently, the mixtures were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 minutes, and the resulting supernatants were analyzed using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer. The absorbance values of C-phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrin were recorded at 562 nm, 615 nm, and 652 nm, respectively. The contents of C-phycocyanin C, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrin were determined through the application of Equations (7)–(9) [25]: 2.6.2. Productivity of Chlorophyll, Carotenoids, and Phycobiliproteins The productivities of chlorophyll a (PChla, mg.L−1.d−1), chlorophyll b (PChlb, mg.L−1.d−1), carotenoids (PCat, mg.L−1.d−1), C-phycocyanin (PC-PC, mg.L−1.d−1), allophycocyanin (PAPC, mg.L−1.d−1) and phycoerythrin (PPE, mg.L−1.d−1) were assessed based on dry biomass, as outlined in Equations (10), (11), (12), (13), (14) and (15) respectively. Where Xf, Chl a, Chl b, Cat, C-PC, APC, PE, and Δt represent dry biomass, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids, C-phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, phycoerythrin, and cultivation time, respectively. 2.6.3. Protein and Cysteine The protein content was analysed using the method outlined by Bradford [26], which relies on the binding of proteins to a dye and the subsequent color change observed between 465 and 595 nm. For protein extraction, S. platensis dry biomass (5 mg) was mixed with 2 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.2) and incubated for 10 min. The resulting mixture was collected after centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C (Sigma 1-15K, Osterode am Harz, Germany). A volume of 0.1 mL of the supernatant was combined with 2 mL of the Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), and subsequently incubated in the dark for 10 min. Afterwards, the solution was transferred into cuvettes and the absorbance was recorded at 595 nm using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (BK-S380, China). The cysteine content was assessed through the method outlined by Gaitonde [27]. Cysteine extraction was performed by mixing S. platensis dry biomass (5 mg) with 5 mL of 80% ethanol and centrifuging it at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Cysteine crude extract (0.15 mL) was mixed with 0.35 mL of acidic ninhydrin reagent [1.3% (w/v) ninhydrin in 1:4 HCl:CH3COOH conc] (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). The mixture was homogenized and heated at 100 °C for 10 min, then cooled on ice. After adding 1 mL of 95% ethanol, the optical density was assessed at 560 nm against a blank containing 80% ethanol instead of the cysteine crude extract.

Jourdan Standard Medium (JM)

Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with M. oleifera Leaf Extract

Constituents

Concentration (g L−1)

Treatments

Constituents

Concentration (g L−1)

(NH2)2CO

0.05

NaHCO3 *

8

(NH4)2HPO4

0.12

NaCl *

5

KNO3

2

CF *

10

MgSO4

0.16

CaCl2

0.02

CF-MLE-0 (control)

0

FeSO4

0.02

CF-MLE-10

MLE *

10

NaCl

5

CF-MLE-15

15

NaHCO3

8

CF-MLE-20

20

Jourdan Standard Medium (JM)

Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract

Components

Price (US Kg−1)

Components

Price (US Kg−1)

(NH2)2CO

342.13

NaHCO3

69.08

(NH4)2HPO4

130.75

NaCl

49.90

KNO3

119.42

CF *

0

MgSO4

233.17

MLE *

0

CaCl2

128.57

FeSO4

82.92

NaCl

49.90

NaHCO3

69.08

Total price

1155.94

Total price

118.98

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the results were presented as means ± standard deviations. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) through analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multiple mean comparisons across different treatments were performed using Tukey’s test with a 95% confidence level. A statistically significant difference was identified when p < 0.05.

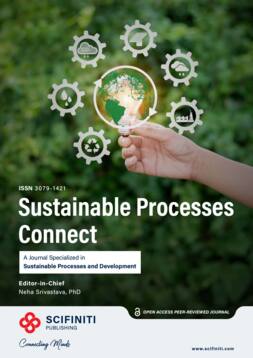

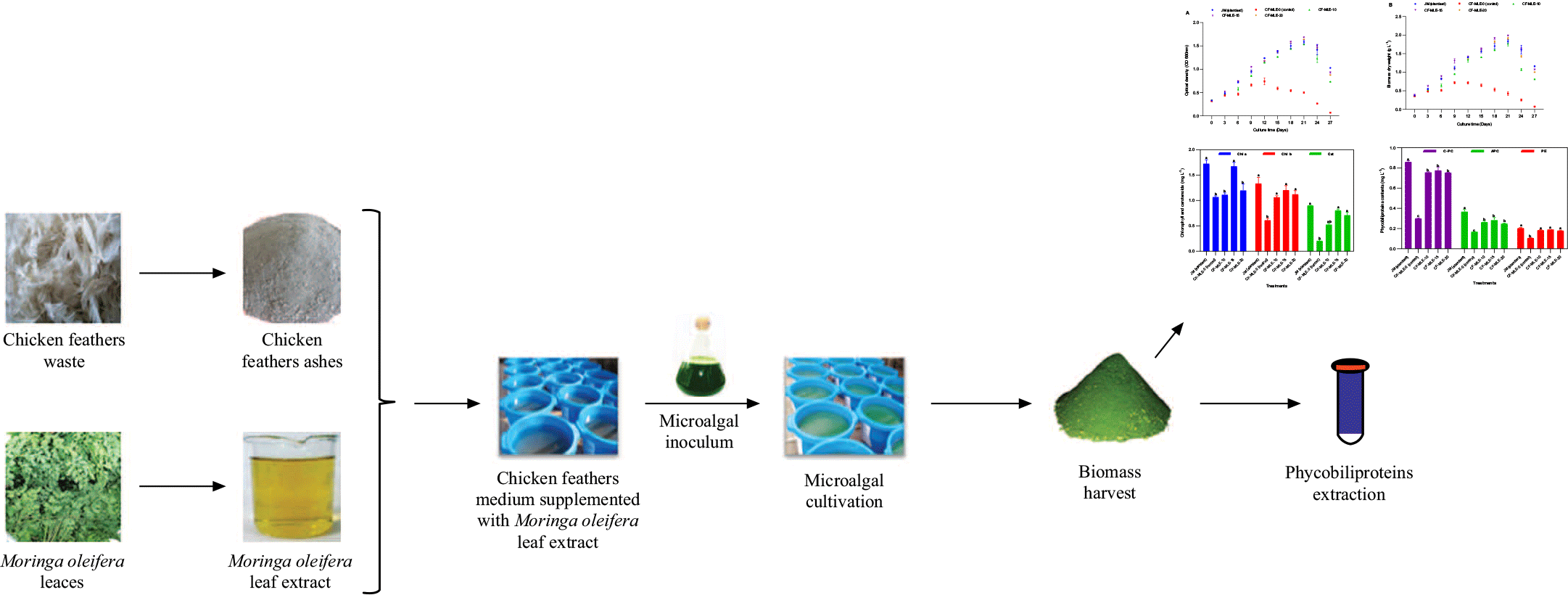

4.1. Effects of Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on Spirulina platensis Growth Performance The variations in the cell density and dry biomass of S. platensis cultivated in CF medium enriched with M. oleifera leaf extract are illustrated in Figure 1A,B. An exponential increase in cell density and dry biomass was noted from day 1 to day 21. However, a significant decrease was observed from day 21 to day 27, especially in the control medium with chicken feather medium, which resulted in reduced growth from day 9 onwards. The chicken feathers medium supplemented with 15 g L−1 M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE-15) presented significantly (p < 0.05) higher cell density (1.68 ± 0.03) and dry biomass (1.98 ± 0.05 g L−1) than standard Jourdan medium (JM), with a cell density and dry biomass of 1.58 ± 0.05 g L−1 and 1.83 ± 0.04 g L−1, respectively. In contrast to the other treatments, the chicken feathers medium without M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE-0) showed the lowest cell density (0.50 ± 0.03) and dry biomass (0.42 ± 0.06 g L−1) of S. platensis (Table 3). These results are attributed to the nutrient content, namely nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, calcium, sodium, and magnesium, present in the leaves of Moringa oleifera and chicken feathers, which collectively enhanced cell growth and carbon metabolism during the photosynthetic activity of Spirulina platensis [22,28,29]. Therefore, CF-MLE-15 is more conducive to growth and consequently higher cell density. The findings presented a higher level of efficacy than those reported by Wamba et al. [15] for a medium containing M. oleifera leaf extract enriched with either kanwa or sodium bicarbonate. The variation observed may be related to the formulation of the medium and the duration of the cultivation. Optical density (OD680 nm), dry biomass (X), biomass productivity (Px), and growth rate (µm) of S. platensis after 27 days of cultivation in chicken feathers medium enriched with M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE). Note: The data are presented as the means ± standard deviations. The means with matching superscript letters (a > b > c > d) within the same column are not significantly different (p > 0.05) according to the Tukey test. Biomass productivity (Px) and growth rate (µ) showed an upward trend in chicken feather media with increasing concentration of M. oleifera leaf extract. It was observed that the standard Jourdan medium resulted in the highest biomass productivity (0.032 ± 0.003 g L−1 d−1) and growth rate (0.040 ± 0.001 d−1). Nonetheless, the CF-MLE-15 medium significantly (p < 0.05) increased the biomass productivity (0.028 ± 0.002 g L−1 d−1) and growth rate (0.038 ± 0.001 d−1) compared with those of the different chicken feathers media supplemented with M. oleifera leaf extract and the control medium (−0.011 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1 and −0.057 ± 0.002 d−1) (Table 3). These findings can be explained by the provision of essential nutrients from Moringa oleifera leaf and chicken feather extracts during the cultivation of Spirulina platensis. These results are congruent with the findings of Suparmaniam et al. [30], emphasizing the essential role of chicken feather nutrients in promoting microalgal growth. 4.2. Effects of Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on the Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents and Productivity of Spirulina platensis The contents of carotenoids, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b in S. platensis biomass cultivated from chicken feathers supplemented with various concentrations of M. oleifera leaf extract are presented in Table 4 and Figure 2. The variations in the carotenoid and chlorophyll a and b contents were correlated with the M. oleifera leaf extract concentrations in the medium. Supplementation of the chicken feathers medium with 15 g L−1 M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE-15) led to a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the carotenoid (0.82 ± 0.02 mg L−1), chlorophyll a (1.67 ± 0.07 mg L−1), and chlorophyll b (1.20 ± 0.09 mg L−1) contents. Nevertheless, the Jourdan standard medium presented significantly higher (p < 0.05) contents of carotenoids (0.90 ± 0.003 mg L−1), chlorophyll a (1.72 ± 0.07 mg L−1), and chlorophyll b (1.33 ± 0.12 mg L−1) than the other treatments. Similarly, the productivity of chlorophyll and carotenoids of S. platensis showed a downward trend with the M. oleifera leaf extract concentration in the chicken feathers medium (Table 5). The productivity of chlorophyll and carotenoids of S. platensis was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in CF-MLE-15 with 0.16 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1 and 0.11 ± 0.002 g L−1 d−1, respectively, than the control (0.02 ± 0.002 g L−1 d−1 and 0.01 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1) (Table 5). The range of chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids in the current study is consistent with that reported by Herrera et al. [31], who reported values between 0.83 and 2.66 mg L−1, using Schlösser and whey media under mixotrophic conditions as a substitute for synthetic media. This increase is attributed to the potassium, calcium, and iron supplied by chicken feather and M. oleifera leaf extracts, which activated metabolic enzymes, regulated cellular processes, and maintained the structural integrity of the photosynthetic apparatus [32,33]. The ability to enrich chicken feathers medium with concentrations of 15 g L−1 MLE was noteworthy, as it influenced growth, dry biomass, and photosynthetic pigments. Conversely, at higher concentrations of MLE, cellular growth and photosynthetic efficiency were significantly reduced, resulting in decreased chlorophyll and carotenoid levels. Furthermore, Saad et al. [34] reported that the pigment content of S. platensis was lower under mixotrophic conditions than autotrophic conditions. Chlorophyll (Chl a and b), total carotenoid (Cat), C-Phycocyanin (C-PC), Allophycocyanin (APC), and Phycoerythrin (PE) contents of S. platensis after 27 days of cultivation in chicken feathers medium enriched with M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE). Note: The data are presented as means ± standard deviations. The means with matching superscript letters (a > b > c > d) within the same column are not significantly different (p > 0.05) according to the Tukey test. Chlorophyll (Chl a and b), total carotenoids (Cat), C-Phycocyanin (C-PC), Allophycocyanin (APC), and Phycoerythrin (PE) productivities of S. platensis after 27 days of cultivation in chicken feathers medium enriched with M. oleifera leaf extract (CF-MLE). Note: The data are presented as means ± standard deviations. The bars represent the standard deviation. The means with matching superscript letters (a > b > c > d) within the same column are not significantly different (p > 0.05) according to the Tukey test. 4.3. Effects of Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on the Phycobiliprotein Content and Productivity of Spirulina platensis The phycobiliprotein contents in the S. platensis biomass grown in the different media are shown in Table 4 and Figure 3. The mean phycocyanin concentrations measured in biomass grown in CF-MLE-10, CF-MLE-15, and CF-MLE-20 were 0.75 ± 0.01, 0.77 ± 0.03, and 0.75 ± 0.01 mg L−1, respectively (Figure 3). Although the phycocyanin content in the JM treatment was higher than that in the CF-MLE treatment, no significant difference was observed. The mean content of phycoerythrin and allophycocyanin, measured in the biomass grown in CF-MLE-15, was 0.28 ± 0.03 and 0.19 ± 0.001 mg L−1, respectively (Figure 3). Similar to the phycocyanin content, the JM treatment exhibited the highest concentrations of phycoerythrin and allophycocyanin, which were not significantly different from those observed in the CF-MLE treatments. The productivity of phycocyanin, phycoerythrin, and allophycocyanin of S. platensis in CF-MLE-15 was found to be similar to the standard medium. This result was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the control treatment, which had a yield of 0.006 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1, 0.003 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1, and 0.002 ± 0.001 g L−1 d−1, respectively (Table 5). The results for phycocyanin content differ from those of Simo et al. [13], who received 0.14, 0.20, and 0.05 mg L−1 for C-phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrin, respectively, in a medium formulated with 8 g L−1 oil palm empty fruit bunch medium. These differences may be attributed to the essential role of potassium and nitrogen supplied by Moringa oleifera leaf extract and chicken feather in the medium. Indeed, activating enzymes involved in phycobiliprotein synthesis affect phycobiliprotein production in metabolic responses to changes in medium nutrient availability, as reported by Baslam et al. [32]. 4.4. Effects of Chicken Feathers Medium Supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on the Protein and Cysteine Contents of Spirulina platensis The protein content of S. platensis biomass grown in chicken feathers medium supplemented with different concentrations of M. oleifera leaf extract is presented in Figure 4. The protein content (94.5 ± 1.52 mg L−1) was higher in CF-MLE-15 than in the other treatments and the control (39.3 ± 4.21 mg L−1). A high protein content (110.2 ± 6.14 mg L−1) was also observed in Jourdan’s standard medium. Compared with the control, the addition of M. oleifera leaf extract to the chicken feather medium significantly increased the protein content of S. platensis biomass in all the treatment groups (p < 0.05). Therefore, mineral elements such as nitrogen, magnesium, and potassium in CF-MLE may be essential cofactors for protein production [35]. The cysteine content of S. platensis grown on CF-MLE-15 (12.5 ± 1.14 mg L−1) and Jourdan standard medium (14.1 ± 0.81 mg L−1) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of the other treatments and the control (3.8 ± 0.27 mg L−1). The cysteine content observed in this study was lower than the 0.16 g L−1 reported by Magwell et al. [36] in MgSO₄-enriched medium. This difference could be explained by the composition of the culture medium in which the microalgae grew.

Culture Medium

Treatments (g L−1)

OD (680 nm)

X (g L−1)

Px (g L−1 d−1)

µ (d−1)

Jourdan (standard)

JM

1.58 ± 0.05 b

1.83 ± 0.04 b

0.032 ± 0.003 a

0.040 ± 0.001 a

Chicken feathers supplemented with M. oleifera leaf extract

CF-MLE-0 (control)

0.50 ± 0.03 c

0.42 ± 0.06 c

−0.011 ± 0.001 d

−0.057 ± 0.002 c

CF-MLE-10

1.53 ± 0.04 b

1.77 ± 0.06 b

0.018 ± 0.001 c

0.029 ± 0.001 b

CF-MLE-15

1.68 ± 0.03 a

1.98 ± 0.05 a

0.028 ± 0.002 b

0.038 ± 0.001 a

CF-MLE-20

1.63 ± 0.04 a

1.90 ± 0.04 a

0.025 ± 0.002 b

0.036 ± 0.001 a

Culture Medium

Treatments

(g L−1)Chl a

(mg L−1)Chl b

(mg L−1)Cat

(mg L−1)C-PC

(mg L−1)APC

(mg L−1)PE

(mg L−1)

Jourdan (standard)

JM

1.72 ± 0.12 a

1.33 ± 0.04 a

0.90 ± 0.003 a

0.86 ± 0.01 a

0.36 ± 0.02 a

0.20 ± 0.007 a

Chicken feathers supplemented with M. oleifera leaf extract

CF-MLE-0

(control)1.06 ± 0.02 c

0.61 ± 0.06 d

0.20 ± 0.001 d

0.30 ± 0.01 c

0.17 ± 0.01 c

0.11 ± 0.003 b

CF-MLE-10

1.11 ± 0.03 b

1.06 ± 0.06 c

0.52 ± 0.001 c

0.75 ± 0.01 b

0.26 ± 0.01 b

0.18 ± 0.005 a

CF-MLE-15

1.67 ± 0.05 a

1.20 ± 0.05 b

0.82 ± 0.002 a

0.77 ± 0.03 b

0.28 ± 0.03 b

0.19 ± 0.001 a

CF-MLE-20

1.19 ± 0.12 b

1.12 ± 0.04 c

0.71 ± 0.002 b

0.75 ± 0.01 b

0.25 ± 0.01 b

0.18 ± 0.005 a

Culture Medium

Treatments

(g L−1)PChla

(g.L−1.d−1)PChlb

(g.L−1.d−1)PCat

(g.L−1.d−1)PC-PC

(g.L−1.d−1)PAPC

(g.L−1.d−1)PPE

(g.L−1.d−1)

Jourdan (standard)

JM

0.15 ± 0.001 a

0.12 ± 0.002 a

0.08 ± 0.0003 a

0.08 ± 0.002 a

0.03 ± 0.003 a

0.02 ± 0.001 a

Chicken feathers supplemented with M. oleifera leaf extract

CF-MLE-0

(control)0.02 ± 0.002 c

0.01 ± 0.001 b

0.004 ± 0.0007 d

0.006 ± 0.001 b

0.003 ± 0.001 b

0.002 ± 0.001 b

CF-MLE-10

0.09 ± 0.001 b

0.09 ± 0.003 a

0.04 ± 0.0004 c

0.06 ± 0.001 a

0.02 ± 0.002 a

0.01 ± 0.001 a

CF-MLE-15

0.16 ± 0.001 a

0.11 ± 0.002 a

0.07 ± 0.0002 a

0.07 ± 0.005 a

0.03 ± 0.004 a

0.02 ± 0.002 a

CF-MLE-20

0.11 ± 0.002 b

0.10 ± 0.001 a

0.05 ± 0.0009 b

0.07 ± 0.001 a

0.02 ± 0.001 a

0.02 ± 0.002 a

This study investigated the potential of chicken feathers and Moringa oleifera leaf extract as eco-friendly media for the production of biomass and photosynthetic pigments from Spirulina platensis. The results revealed that the biomass production, protein, and photosynthetic pigment contents were related to the concentration of M. oleifera leaf extract in chicken feather media. The highest biomass, protein, and photosynthetic pigment content were observed in the chicken feather medium supplemented with 15 g L−1 M. oleifera leaf extract, in addition to the standard medium. Thus, chicken feathers and M. oleifera leaf extract have emerged as promising and eco-friendly approaches for co-producing biomass and pigments from S. platensis for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, food, and cosmetic applications. Future research should focus on the life cycle assessment and scalability of the CF-MLE-15 medium in photobioreactors to evaluate its performance, cost-effectiveness, and feasibility for industrial Spirulina platensis production.

| APC | Allophycocyanin |

| PAPC | Allophycocyanin Productivity |

| Cat | Carotenoid |

| PCat | Carotenoid Productivity |

| CF | Chicken Feathers |

| CF-MLE | Chicken Feathers medium supplemented with Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract |

| Chl a | Chlorophyll a |

| PChla | Chlorophyll a Productivity |

| Chl b | Chlorophyll b |

| PChlb | Chlorophyll b Productivity |

| C-PC | C-phycocyanin |

| PC-PC | C-phycocyanin Productivity |

| pH | Measure of Acidity or Alkalinity (Potential of Hydrogen) |

| JM | Jourdan Medium |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| MLE | Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract |

| OD | Optical Density |

| PE | Phycoerythrin |

| PPE | Phycoerythrin Productivity |

Conceptualization and design: O.S.W.F., P.F.R.M., C.L. and C.S. Supervision: C.S., E.M., O.S.W.F. and L.G.L. Methodology: O.S.W.F., C.S., P.F.R.M., C.L., K.T.D., B.G.N. and P.L.N.N. Writing—original draft preparation: O.S.W.F., C.S., P.F.R.M., C.L., B.G.N. and K.T.D. Design and visualization of figures: O.S.W.F., P.F.R.M., and C.L. Edited, reviewed the manuscript and provided critical input and corrections: O.S.W.F., C.S. and P.F.R.M. All the authors have approved the final version of the published manuscript.

Data supporting the results of the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

This research did not receive specific funding from public, commercial, or non-profit entities.

The authors greatly acknowledge the SAGRIC farm in Douala, Cameroon, for supplying the Spirulina platensis strain used in the current study.

[1] Dhandwal, A.; Bashir, O.; Malik, T.; Salve, R.V.; Dash, K.K.; Amin, T.; Wani, A.W.; Shah, Y.A. Sustainable microalgal biomass as a potential functional food and its applications in food industry: A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 1–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2] Siddiki, S.Y.A.; Mofijur, M.; Kumar, P.S.; Ahmed, S.F.; Inayat, A.; Kusumo, F.; Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.M.Y.; Nghiem, L.D.; Ong, H.C.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Microalgae Biomass as a Sustainable Source for Biofuel, Biochemical and Biobased Value-Added Products: An Integrated Biorefinery Concept. Fuel 2022, 307, 121782. [CrossRef]

[3] AlFadhly, N.K.Z.; Alhelfi, N.; Altemimi, A.B.; Verma, D.K.; Cacciola, F. Tendencies Affecting the Growth and Cultivation of Genus Spirulina: An Investigative Review on Current Trends. Plants 2022, 11, 3063. [CrossRef]

[4] Bortolini, D.G.; Maciel, G.M.; Fernandes, I.D.A.A.; Pedro, A.C.; Rubio, F.T.V.; Branco, I.G.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Functional Properties of Bioactive Compounds from Spirulina Spp.: Current Status and Future Trends. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100134. [CrossRef]

[5] Marjanović, B.; Benković, M.; Jurina, T.; Sokač Cvetnić, T.; Valinger, D.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Jurinjak Tušek, A. Bioactive Compounds from Spirulina Spp.—Nutritional Value, Extraction, and Application in Food Industry. Separations 2024, 11, 257. [CrossRef]

[6] Amin, M.; ul Haq, A.; Shahid, A.; Boopathy, R.; Syafiuddin, A. Spirulina as a Food of the Future. In Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Potential of Cyanobacteria; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 53–83. [CrossRef]

[7] Gentscheva, G.; Nikolova, K.; Panayotova, V.; Peycheva, K.; Makedonski, L.; Slavov, P.; Radusheva, P.; Petrova, P.; Yotkovska, I. Application of Arthrospira platensis for Medicinal Purposes and the Food Industry: A Review of the Literature. Life 2023, 13, 845. [CrossRef]

[8] Mittal, R.K.; Krishna, G.; Sharma, V.; Purohit, P.; Mishra, R. Spirulina Unveiled: A Comprehensive Review on Biotechnological Innovations, Nutritional Proficiency, and Clinical Implications. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2025, 26, 1441–1458. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9] Markou, G.; Kougia, E.; Arapoglou, D.; Chentir, I.; Andreou, V.; Tzovenis, I. Production of Arthrospira platensis: Effects on Growth and Biochemical Composition of Long-Term Acclimatization at Different Salinities. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 233. [CrossRef]

[10] De Carvalho, J.C.; Sydney, E.B.; Assú Tessari, L.F.; Soccol, C.R. Culture media for mass production of microalgae. In Biofuels from Algae; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 33–50. [CrossRef]

[11] Markou, G.; Wang, L.; Ye, J.; Unc, A. Cultivation of Microalgae on Anaerobically Digested Agro-Industrial Wastes and By-Products. In Application of Microalgae in Wastewater Treatment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 147–172. [CrossRef]

[12] De Souza, D.S.; Valadão, R.C.; de Souza, E.R.P.; Barbosa, M.I.M.J.; de Mendonça, H.V. Enhanced Arthrospira platensis Biomass Production Combined with Anaerobic Cattle Wastewater Bioremediation. BioEnergy Res. 2021, 15, 412–425. [CrossRef]

[13] Simo, C.; Wamba, F.O.; Nyabeu, N.P.L.; Magwell, P.F.R.; Maffo, N.M.L.; Tchoffo, D.K.; Minyaka, E.; Lehman, L.G. Enhanced Spirulina Platensis Growth for Photosynthetic Pigments Production in Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch Medium. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2023, 10, 52–63. [CrossRef]

[14] Nweze, N.O.; Nwafor, F.I. Promoting Increased Chlorella Sorokiniana Shih. Et Krauss (Chlorophyta) Biomass Production Using Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf Extracts. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 4720–4725. [CrossRef]

[15] Wamba, F.O.; Magwell, P.F.R.; Tchoffo, K.D.; Bahoya, A.J.; Minyaka, E.; Tavea, M.; Lehman, L.G.; Taffouo, V.D. Physiological and Biochemical Traits, Antioxidant Compounds and Some Physico-Chemical Factors of Spirulina Platensis Cultivation as Influenced by Moringa Oleifera Leaves Extract Culture Medium Enriched with Sodium Bicarbonate and Kanwa. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 20, 325–334. [CrossRef]

[16] Abbas, R.K.; Elsharbasy, F.S.; Fadlelmula, A.A. Nutritional Values of Moringa oleifera, Total Protein, Amino Acid, Vitamins, Minerals, Carbohydrates, Total Fat and Crude Fiber, under the Semi-Arid Conditions of Sudan. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2018, 10, 56–58. [CrossRef]

[17] Srivastava, S.; Pandey, V.K.; Dash, K.K.; Dayal, D.; Wal, P.; Debnath, B.; Singh, R.; Dar, A.H. Dynamic Bioactive Properties of Nutritional Superfood Moringa Oleifera: A Comprehensive Review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100860. [CrossRef]

[18] Adekiya, A.O. Green Manures and Poultry Feather Effects on Soil Characteristics, Growth, Yield, and Mineral Contents of Tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108721. [CrossRef]

[19] Bhari, R.; Kaur, M.; Sarup Singh, R. Chicken Feather Waste Hydrolysate as a Superior Biofertilizer in Agroindustry. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2212–2230. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20] Chaturvedi, V.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. Chicken feathers: A treasure cove of useful metabolites and value-added products. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 231–243. [CrossRef]

[21] Simões, A.R.; de Souza, A.T.; Meurer, E.C.; Scaliante, M.H.N.O.; Cortelo, T.H. Moringa oleifera: Technological innovations and sustainable therapeutic potencials. Cad. Pedagógico 2025, 22, e13594. [CrossRef]

[22] Tesfaye, T.; Sithole, B.; Ramjugernath, D.; Chunilall, V. Valorisation of Chicken Feathers: Characterisation of Chemical Properties. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 626–635. [CrossRef]

[23] Magwell, P.F.R.; Nedion, N.J.; Tavea, M.F.; Wamba, F.O.; Tchoffo, D.K.; Maffo, N.M.L.; Medueghue, F.A.; Minyaka, E.; Lehman, L.G. The Effect of Low-Cost NPK 13-13-21 Fertilizer on the Biomass and Phycobiliproteins Production of Spirulina platensis. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 11, 45–55. [CrossRef]

[24] Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Babani, F. Contents of Photosynthetic Pigments and Ratios of Chlorophyll A/B and Chlorophylls to Carotenoids (A+B)/(X+C) in c4 Plants as Compared to c3 Plants. Photosynthetica 2021, 60, 3–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25] Sharma, G. Effect of Carbon Content, Salinity and PH on Spirulina platensis for Phycocyanin, Allophycocyanin and Phycoerythrin Accumulation. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2014, 6, 202–206. [CrossRef]

[26] Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976 [CrossRef]

[27] Gaitonde, M. A Spectrophotometric Method for the Direct Determination of Cysteine in the Presence of Other Naturally Occurring Amino Acids. Biochem. J. 1967, 104, 627–633. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28] Hizam, N.S.; Omar, N.; Sabri, N.; Samsuddin, N.Z.; Abidin, M.Z. Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties and Nutrient Composition of Chicken Feather Vermicompost for Sustainable Waste Management System. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1426, 012014. [CrossRef]

[29] Arif, Y.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Moringa oleifera Extract as a Natural Plant Biostimulant. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 42, 1291–1306. [CrossRef]

[30] Suparmaniam, U.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, J.W.; Rawindran, H.; Chai, Y.H.; Tan, I.S.; Fui Chin, B.L.; Kiew, P.L. The Potential of Waste Chicken Feather Protein Hydrolysate as Microalgae Biostimulant Using Organic Fertilizer as Nutrients Source. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1074, 012028. [CrossRef]

[31] Herrera-Peralta, C.; Maldonado-Pereira, L.; Cantú-Lozano, D.; Medina-Meza, I.G. Mixotrophic Cultivation Boost Nutraceutical Content of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis. agriRxiv 2022, 2022, 20220173394. [CrossRef]

[32] Baslam, M.; Mitsui, T.; Sueyoshi, K.; Ohyama, T. Recent Advances in Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in C3 Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 318. [CrossRef]

[33] Chan, S.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Ling, T.C.; Chae, K.J.; Srinuanpan, S.; Khoo, K.S. Unlocking the potential of food waste as a nutrient goldmine for microalgae cultivation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 492, 144753. [CrossRef]

[34] Saad, S.; Hussien, M.H.; Abou-ElWafa, G.S.; Aldesuquy, H.S.; Eltanahy, E. Filter cake extract from the beet sugar industry as an economic growth medium for the production of S. platensis as a microbial cell factory for protein. Microb. Cell Factories 2023, 22, 136. [CrossRef]

[35] Asoka, M.G.; Abu, G.O.; Agwa, O.K. Proximate and Physicochemical Composition of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 17, 026–032. [CrossRef]

[36] Magwell, P.F.R.; Minyaka, E.; Fotsop, O.W.; Leng, M.S.; Lehman, L.G. Influence of Sulphate Nutrition on Growth Performance and Antioxidant Enzymes Activities of Spirulina platensis. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 13, 115. [CrossRef]

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more