APA Style

Bruna A. S. Rodrigues, Cristian Henrique De Lima Machado, Caio M. P. Mendonça, Emanuelle S. Prudente, Ana Carolina B. Furtado, Gustavo G. Fontanari, Andrea Komesu, Luiza H. S. Martins. (2025). Drying Kinetics and Thermodynamic Properties of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) Peel as a Sustainable Agro-Industrial By-Product. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0014). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.1993765MLA Style

Bruna A. S. Rodrigues, Cristian Henrique De Lima Machado, Caio M. P. Mendonça, Emanuelle S. Prudente, Ana Carolina B. Furtado, Gustavo G. Fontanari, Andrea Komesu, Luiza H. S. Martins. "Drying Kinetics and Thermodynamic Properties of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) Peel as a Sustainable Agro-Industrial By-Product". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0014, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.1993765.Chicago Style

Bruna A. S. Rodrigues, Cristian Henrique De Lima Machado, Caio M. P. Mendonça, Emanuelle S. Prudente, Ana Carolina B. Furtado, Gustavo G. Fontanari, Andrea Komesu, Luiza H. S. Martins. 2025. "Drying Kinetics and Thermodynamic Properties of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) Peel as a Sustainable Agro-Industrial By-Product." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0014. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.1993765.

ACCESS

Research Article

ACCESS

Research Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0014

Bruna A. S. Rodrigues

brunarodrigues.cta@gmail.com

Cristian Henrique De Lima Machado

henriquemachado16042003@gmail.com

Caio M. P. Mendonça

caiomiguelpantoja@gmail.com

Emanuelle S. Prudente

emanuelleprudente4@gmail.com

Ana Carolina B. Furtado

anac4rolina044@gmail.com

Gustavo G. Fontanari

gustavo.fontanari@ufra.edu.br

Andrea Komesu

andrea.komesu@unifesp.br

Luiza H. S. Martins

luiza.martins@ufra.edu.br

1 Instituto de Saúde e Produção Animal, ISPA, Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia, Belém 66077-830, PA, Brazil

2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia Aplicada à Agropecuária (PPGBAA), Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia, Terra Firme, Belém 66077-830, PA, Brazil

3 Instituto do Mar, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Santos 11070-100, SP, Brazil

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 04 Mar 2025 Accepted: 03 Sep 2025 Available Online: 04 Sep 2025 Published: 23 Sep 2025

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), an important crop in the North and Northeast of Brazil, is primarily cultivated for flour and starch production. Large quantities of peel are generated as waste, which represents a valuable by-product in the food industry. This study investigated the potential of cassava peel as a sustainable by-product for the food industry, focusing on the mathematical modeling of drying kinetics and thermodynamic properties. Cassava peel has a high moisture content, which limits its conservation and favors microbial growth. Cassava peels were collected, analyzed, and processed. Physicochemical analyses were conducted, revealing the following composition: moisture (71.00%), ash (8.15%), lipids (0.29%), proteins (4.70%), and starch (42.12%). In addition, the bioactive compounds were evaluated through Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC) (12.50 mg GAE/g) and antioxidant activity (AA) by the ABTS method (150.00 µmol TE/g). Drying was conducted at temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C, and the data were fitted to five mathematical models. The logarithmic model presented the best fit, with coefficients of determination (R2) above 0.99 and the lowest standard error (SE) and chi-square (χ2). Drying at 50 °C better preserved total TPC (9.10 mg GAE/g) and AA (80.00 µmol TE/g), while higher temperatures reduced these compounds but maintained starch content (39.12–42.2 g/100 g). Thermodynamic parameters ∆H, ∆S, and ∆G indicated that drying is a non-spontaneous process requiring external energy. This work highlights the viability of using cassava peel as a sustainable resource, contributing to the reduction of agro-industrial waste.

Cassava peel is a sustainable by-product with nutritional and functional potential for the food industry. Cassava peel showed relevant levels of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity. The logarithmic model best described the drying kinetics with high accuracy (R2 > 0.99). Drying at 50 °C preserved bioactive compounds, while higher temperatures maintained starch. Thermodynamic parameters indicated drying as a non-spontaneous and energy-dependent process.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is of considerable socioeconomic importance worldwide, serving as a primary source of carbohydrates for millions of people, particularly in developing countries. This crop plays a significant role in generating employment and income, especially for family farmers in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil [1]. The two main products of cassava are flour and starch (sweet cassava starch, or gum). In the industrial processing of cassava in Brazil, approximately 80% of the national root production is used for flour manufacture, 3% for starch extraction, and the remainder for animal feed [2]. In the processing of cassava, the peel is one of the most generated residues during the manufacture of flour or starch, consisting, in addition to the peels themselves (brown film), of inter-peel, debris from the cortex and root tips, and high moisture content [3]. The disposal of urban solid waste does not always occur due to a lack of waste management but rather due to automatic behavior and a lack of responsibility linked to the desire to discard the material [4]. The global trend to reduce industrial waste is growing, and more solutions for proper and profitable disposal are being sought. Cassava peel is a promising residue with significant chemical and biotechnological potential and can be utilized for the production of bioinputs, including biochar [5], bioethanol, and silage for animal feed [6,7]. The peels have a high moisture content, which must be reduced to limit biological and biochemical activities, thereby enhancing the shelf life and stability of potential products during storage. The drying process reduces the water content to safe levels for storage, as it involves heat and mass transfers. The drying conditions and methods employed influence both the biological activity and the chemical and physical structure of the seeds [8]. Drying is a traditional conservation method and a long-established unit operation used to preserve perishable products. It allows reducing the water content and increasing the storage period of the product, preventing the growth of microorganisms and insects, and reducing the mass and volume to be transported [9]. Kinetics and mathematical modeling are important and widely employed tools for optimizing various drying processes of food products. Drying kinetics is a topic commonly covered in literature for various products. The temperature and the flow and/or speed of the air used [9] are among the most important variables. According to Lopes de Menezes et al. [10], drying allows the analysis of solid material behavior through curves relating the moisture ratio to time and drying rate. These curves contain essential information for developing the process and for better dimensioning of the equipment, making it possible to evaluate the time required to dry a certain quantity of products. This work aimed to study the mathematical modeling of cassava peel drying kinetics, evaluating four different temperatures to optimize the processing time and preserve the quality of phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and starch content. The focus was on using cassava peels from industrial waste for biotechnological applications. In addition, essential thermodynamic parameters, fundamental for the design of drying equipment and the calculation of required energy, were analyzed, providing a deeper understanding of the physical phenomena occurring during the process [9].

2.1. Sample Collecting The cassava was collected in the municipality of Parauapebas, PA, Brazil, located at 06°12′58″ S latitude and 49°51′19″ W longitude, with an altitude of 197 m. The samples were transported to the city of Belém-PA and taken to the food laboratory of the Federal Rural University of the Amazon for sanitization (100 mg/L) for 15 min, followed by washing with chlorinated water at 10 mg/L to remove excess chlorine. The cassava was cut, the peels separated from the pulp, and vacuum-packed in polyethylene bags, then stored at −18 °C until analysis. This sample was coded as cassava peels or RCP. The dried cassava peels were designed as DCP. 2.2. Physicochemical Characterization The physicochemical analyses generally followed the methods of Adolf Lutz [11] for the raw residue. The samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the determinations performed were for water activity (4TE, AquaLab, USA), total soluble solids (TSSºBrix) measured in a refractometer (Portable refractometer, model KASVI, Brazil.), pH measured in a benchtop pH meter (KASVI, K39-1420A, Brazil), total titratable acidity (TTA), moisture, ash, lipids, and proteins. Starch content was analyzed for the RCP, and after drying at three different temperatures, to evaluate the effect of temperature on starch extraction [12]. 2.3. Analysis of Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC) The hydroalcoholic extract for this analysis was prepared according to the methodology of Guindani et al. [13]. This analysis was performed for both RCP and DCP at all studied temperatures. TPC determination was performed according to the methodology proposed by Singleton and Rossi [14], modified for microplates, in a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Oy, Multiskan Go-SN-1530-8001397, Finland). The absorbance reading was performed at a wavelength of 765 nm. The concentration of TPC in the extracts was determined from the equation of the straight line obtained in the standard curve of gallic acid (Sigma, 99% purity) (y = 0.0059x + 0.0929, R2 = 0.9996) and expressed in mg GAE/g of the sample. 2.4. Antioxidant Activity by the ABTS Method The antioxidant capacity of the RCP hydroalcoholic extracts against the free radical ABTS•+ (2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) was evaluated according to the methodology proposed by Rufino et al. [15] with modification. Quantification was performed using Trolox ((±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid, 97%, Sigma, Brazil) to construct the analytical curve (y = −0.0005x + 0.6844, R2 = 0.9911). From the straight-line equation, the calculation was performed and expressed in µM Trolox equivalent/g of sample. This analysis was performed for both RCP and DCP. 2.5. Drying Kinetics The drying kinetics of cassava residues occurred by convection, with an average of 25.00 g of peels weighed on stainless steel trays (3 mm) with an area of 204 cm2 and a height of 1 cm. The process took place in an oven with forced air circulation (Model EL 1.3 Odontobrás) at temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C until reaching constant mass [16]. The process was carried out with an air speed of 1.4 m/s on the digital anemometer (Model AD-250 Instrutherm). These conditions were determined based on preliminary tests and the studies of Vilhalva et al. [8] and Kosasih et al. [17], as well as the selection of the mathematical models used in this study. After this stage, the resulting samples were ground in a processor (W, RI7625), packaged, and stored in a hermetically sealed polyethylene bag under a vacuum for future analysis. Using the obtained results, curves relating moisture content (Y) to process time were constructed according to Equation (1).

The thickness of the cut cassava peels was calculated using a digital caliper with a resolution of 0.01 mm [18]. To ensure greater representativeness, 100 repetitions of the material were performed in different parts of the waste. An arithmetic mean was calculated for these 100 measured parts.

To calculate the effective diffusion coefficient, we used the theory of water migration by diffusion as a basis, based on Fick’s second law, which was considered in the study of drying kinetics. Considering that a flat plate can represent the mass of cassava peel residues, Equation (1) was used as proposed by Crank [19]:

The Arrhenius equation, described in Equation (3), was used to evaluate the influence of temperature on the effective diffusion coefficient.

Equation (3) can be linearized to determine the activation energy (Ea) of the drying process, as shown in the following Equation (4).

2.6. Adjustments to Mathematical Models

In predicting drying curves, mathematical adjustments of classical models that describe the kinetics of drying processes in foods were evaluated (Table 1). These models describe the kinetics of the drying processes applied in present work. The models were adjusted by nonlinear regression to the results obtained in the drying experiments using the Statistica software (version 7.1, StatSoft Inc., USA). The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used as a 10−6 convergence criteria [16].

Models used to describe the drying curves of different food matrices.

| Model | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Logarithmic | Y = a.exp(k.tn) + c | Toğrul; Pehlivan [20] |

| Diffusion Approximation | Y = a·e-k.t + (1a)·e-k.b.t | Corrêa et al. [21] |

| Newton | Y = e –k.t | Faria et al. [22] |

| Henderson & Pabis | Y = a.exp(-k.t) | Henderson & Pabis (1974) [23] |

| Wang & Singh | Y = 1 + a.t + b.t2 | Wang; Singh (1978) [24] |

Y = moisture rate (dimensionless), t = residence time (s), and a, b, c, and k are model constants.

The models were selected considering the magnitude of the estimate’s standard deviation (SE). The values of the coefficient of determination (R2) and chi-square (χ2) were used to determine the model that best describes the drying curves according to Martins and Pena [16]. The SE and χ2 values for each model were estimated by Equations (5) and (6), respectively.

For a model to provide a good fit, it should meet the following criteria: R2 close to 1, and SE and χ2 close to zero.

2.7. Calculation of Thermodynamic Parameters

The thermodynamic properties of enthalpy (Equation (7)), entropy (Equation (8)), and Gibbs free energy (Equation (9)) in the drying process of cassava peels at different temperatures (50, 60, 70, and 80 °C) were determined using the method presented by Silva et al. [25].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

For the physical-chemical, TPC, and ABTS determinations, averages, standard deviations, and the coefficient of variation were calculated (considering up to 10% for physical-chemical analyses and up to 15% for TPC and ABTS analyses).

ANOVA and Tukey analysis (after the data were analyzed by Shapiro-Wilk and presented as a normal distribution) were performed to compare the means of the TPC, AA, and starch analyses after drying the material at temperatures of 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C and assess whether there was a significant difference between the treatments.

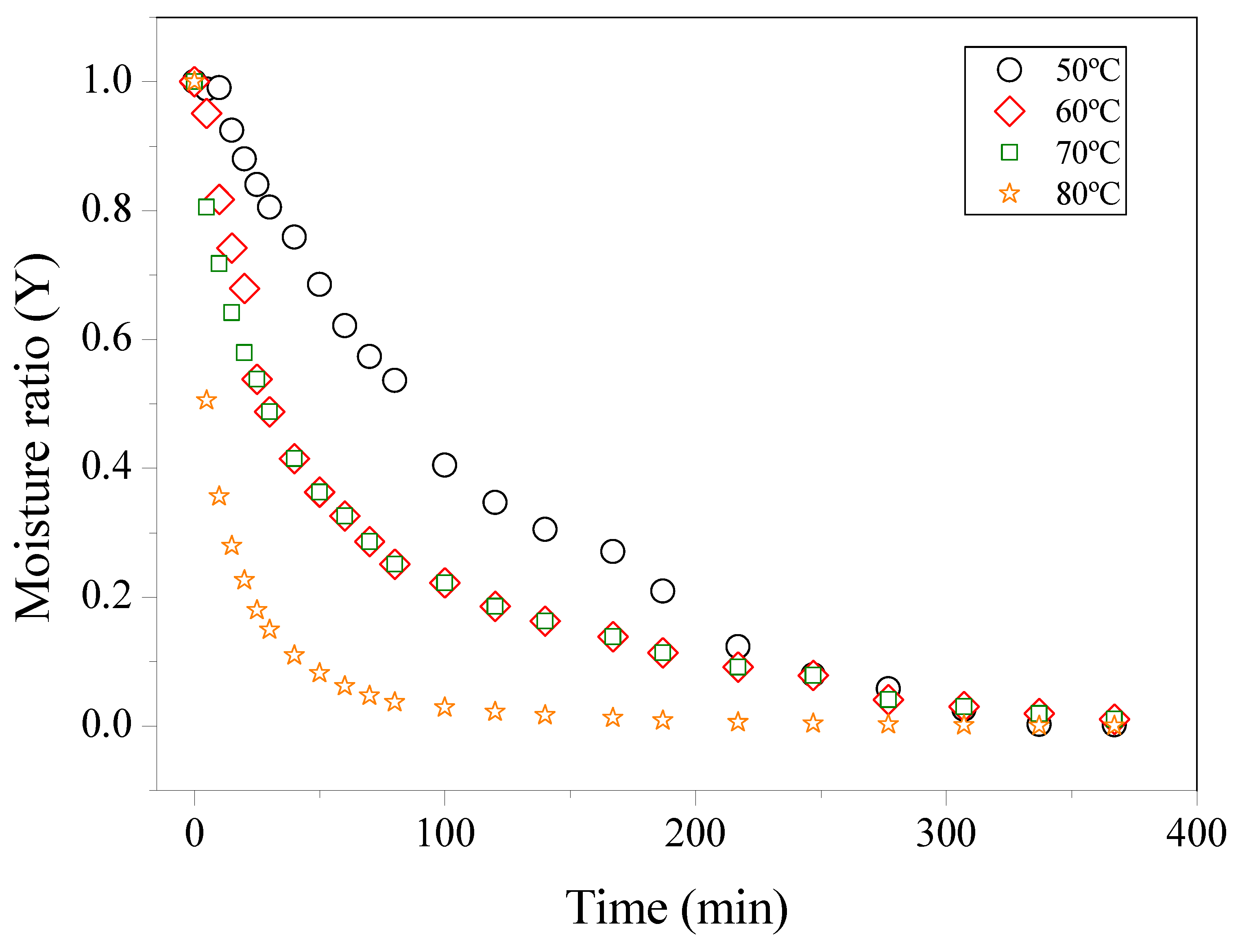

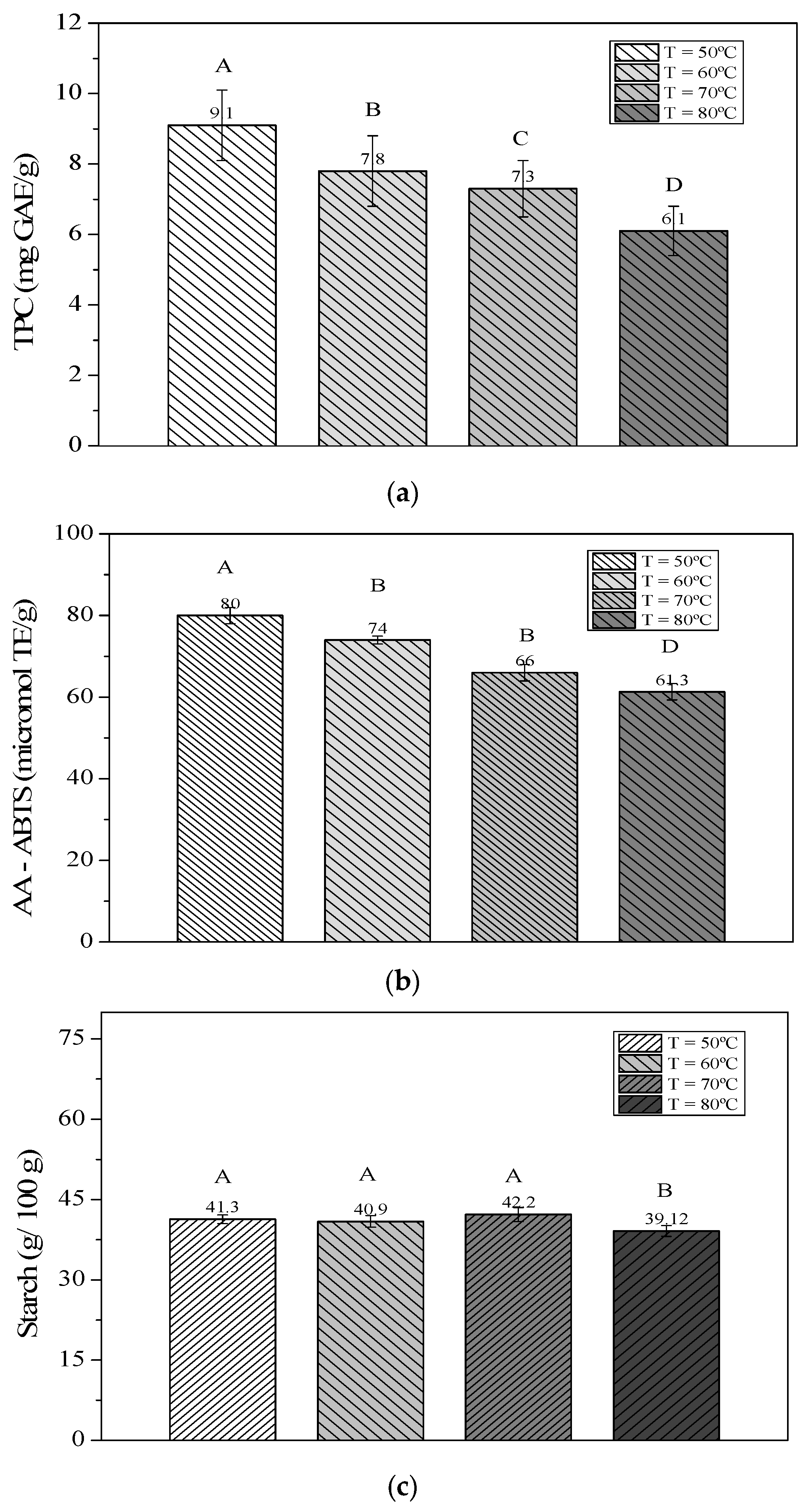

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of the Residue Table 2 presents data on the centesimal and chemical composition (on a dry basis) of raw cassava peels (RCP). Centesimal and chemical composition of RCP. According to Tapia et al. [26], aw analysis is a determining factor in foods’ microbiological stability and enzymatic activity. Therefore, controlling water activity and humidity are fundamental factors in preserving the quality of the product. The peels obtained water activity or aw values from 0.981 to 0.9956, with an average of 0.996. These results demonstrate that the sample is perishable and that the probability of it undergoing chemical, physical, microbiological, or enzymatic reactions is much higher. Souto [27] found the following compositions for cassava peel: 72.53 g/100 g of moisture, 1.63 ± 0.04 g/100 g of ash, 0.86 g/100 g of lipids, and 3.97 g/100 g of protein. Regarding pH, the author obtained a value of 4.85, while for Total Acid Titration (TTA), the value found was 5.18 mL of 1 M NaOH per 100 g. The starch content was 60.68 g/100 g. In the present study, the results were similar to those reported by Souta [27], although considerably lower values were observed for starch and lipids. On the other hand, the protein content was slightly higher, while the moisture and ash values presented results close to those found by this author. The values of the present research were also compared with those found by Batista et al. [28] for cassava peel, which were as follows: pH of 5.64, TTA of 4.13 mL of 1 M NaOH (100 g), water activity of 0.996, moisture of 70.96 (g/100 g), ash of 8.95 (g/100 g), lipids of 0.26 (g/100 g), and protein of 4.08 (g/100 g). The sample’s total soluble solids (TSS) content shows that cassava peel retains a low °Brix value. Pinto et al. [29] found a ºBrix value varying from 2 to 3.9 for cassava flour. The ash percentage of the sample had an average value of 8.15 g/100 g. This high ash value may indicate the presence of minerals in the roots, which is understandable, since this is in direct contact with the soil during its collection. Regarding TPC and AA measured by ABTS, it is important to note that such variations are common among vegetables and can be influenced by factors including plant variety, soil type, climate, and cultivation conditions [30]. Batista et al. [27] also measured TPC in cassava peel extracts (hot water extraction) and found values ranging from 10 to 15 mg GAE/g. These results are similar to those found in this work (12.50 ± 1.80). Santos et al. [31] investigated the extraction of phenolic compounds from cassava leaves using different solvent mixtures: (1) Methanol/water 50:50 (v/v), (2) Ethanol/water 50:50 (v/v), and (3) Acetone/water 70:30 (v/v). These authors performed chromatographic identification by HPLC, obtaining catechin, gallic acid, epigallocatechin, chlorogenic acid, and gallocatechin as the major compounds. The authors also found 233.17 to 383.33 μmol trolox/g for AA by ABTS. 3.2. Mathematical Modeling The cassava peel was dried at four different temperatures, 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C, until reaching final water contents on a dry basis (ds) of 1.35, 1.23, 1.28, and 1.19, respectively. All samples achieved these final moisture levels in approximately 7 hours on average. Figure 1 shows the profile of the drying kinetics curves at different temperatures (50, 60, 70, and 80 °C). The results obtained in this analysis will be adjusted in mathematical models to verify which model best fits the drying conditions studied in this work. Table 3 presents the values of the statistical parameters SE, R2, and the chi-square test (χ2), which were used to compare the 5 mathematical models analyzed through nonlinear regression to describe the drying behavior of cassava peel at different temperatures. Values of the parameters of the adjustments of the mathematical models to the drying kinetics data of DCP. Table 3 shows that the coefficient of determination (R2) values were greater than 0.95 until the Henderson and Pabis model, evidencing a satisfactory representation of the drying process. However, upon examining the Wang and Singh model, it is evident that the fit was unsatisfactory for the experimental data at 60 °C and 70 °C, and completely inadequate at 80 °C, indicating that this model is not suitable for these data. According to Lopes de Menezes [10], the closer R2 is to the value 1, the better the model representation. However, when considered in isolation, the coefficient of determination (R2) is not a reliable criterion for selecting nonlinear models [32]. Analyzing the results, the estimated mean error (SE) values for all models at different temperatures were very low, with a maximum value of 0.0641 for the temperature of 60 °C in the Henderson and Pabis models. For Draper and Smith [33], the lower the SE value, the better the fit of the model and the better its ability to describe the dynamics of the drying process. In the chi-square test (χ2), the values recorded for the different adjusted models presented very low results. Lima et al. [34] reported that the efficiency of a mathematical model for the drying process is related to the lowest chi-square value. In the study by Modesto Junior et al. [35] on the mathematical modeling of cassava leaf drying kinetics, R2 values exceeded 0.95 for all model fits to the experimental data, indicating that the models accurately described the drying processes. Also, in this study, the authors reported χ2 values lower than 0.005 and SE lower than 0.07, confirming that all models accurately described the drying kinetics in the experimental domain. The Logarithmic model (Figure 2a) was chosen to calculate the value of the drying constant k (because this model had the best metric fit for all temperatures when compared to the other models tested), which was used to calculate Deff to continue with the calculations of the thermodynamic parameters (Table 4). Thermodynamic properties for DCP at different temperatures with the Logarithmic model. The residual plot (Figure 2b) for the drying kinetics shows points randomly distributed around zero with no apparent systematic trends, indicating that the logarithmic model adequately describes the drying process. The residuals also showed approximate homoscedasticity, without strong signs of increasing or decreasing variance over time. In this analysis, no evidence of clustering or systematic deviations was observed. Residual analysis enables verification of the model’s adequacy in describing the process, which is essential for selecting the most appropriate model. The logarithmic model was selected not only because it presented a better statistical fit but also because it reflects the expected behavior of the studied process. Furthermore, interpreting the results in terms of relative variations facilitates their practical application and the determination of optimal conditions in an industrial context. Oliveira et al. (2015) [36], in their study on strawberry drying using a forced-air circulation oven, also found that the logarithmic model provided the best fit for their data. This type of model describes situations in which there are rapid initial gains, followed by stabilization, which is consistent with the dynamics of food systems. Vilhava et al. [9] found Deff values ranged from 1.87 to 3.57 × 10−9 m2/s for cassava peels at different conditions. According to Cuevas et al. [37], Deff is an important parameter in the food drying process, as it helps in planning and modeling mass transfer. This value may vary depending on the material thickness and the external drying conditions. Santos et al. [36] Deff values ranged between 0.5666 and 1.4245 × 10−¹⁰ m2/s for patuá (Oenocarpus bataua) pulp fruit. As stated by Goneli et al. [18] when the drying temperature is increased, it results in a decrease in water viscosity, a parameter used to measure fluid resistance. The reduction in viscosity facilitates the diffusion of water present in the leaf capillaries. The increase in Deff with increasing temperature can be explained by the rise in vibrations of water molecules, which intensifies the diffusion of this water. As the temperature increased from 50 to 80 °C, the enthalpy decreased from 66.64 to 66.39 kJ/mol, indicating that less energy is required for drying at higher temperatures, consistent with the findings of Corrêa et al. [21] and by Silva et al. [25] for coffee drying and Capsicum chinense L, respectively. The entropy ranged from −276.01 to −257.76 J/mol.K, with lower values at higher temperatures, suggesting greater order in the arrangement of water molecules, which may be related to structural modifications in the product. The Gibbs free energy increased from 134.25 to 137.82 × kJ/mol, indicating that drying is a non-spontaneous process, requiring additional energy from the environment to occur, as also observed by Corrêa et al. [21] and Silva et al. [25]. Silva et al. [24] found values of ΔH ranged from 32.99 to 33.32 kJ/mol, ΔS −295.7 to −296.7 Jmol/K, and ΔG of 131.85 to 143.70 kJ/mol for pepper species Capsicum chinense L. Lower ΔS values at higher temperatures indicate greater order in the interactions between water molecules and the vegetable, suggesting reduced molecular excitation [38]. Furthermore, negative entropy values may reflect chemical or structural changes in the product during drying. When the ΔG presents positive values, this indicates that drying is a non-spontaneous process; that is, it requires the supply of external energy from the environment for the reaction to occur [39]. Energy activation (Ea) represents the difficulty water molecules must overcome to overcome the energy barrier during their movement within the product. According to Kayacier and Singh [40], this energy tends to decrease as the water content of the product increases. In drying processes, lower energy activation values are associated with greater water diffusivity within the material [39]. The energy activation (Ea) for the net diffusion of DCP, calculated as the slope of the line obtained from ln(Deff), was 69.32 kJ/K·mol; this result was considerably higher than the values reported by Kosasih et al. [17], who studied the drying of elephant cassava slices using natural convection in a moisture analyzer and forced convection at temperatures of 60 °C, 80 °C, 100 °C the Ea found for them varied between 22.915 kJ/mol and 27.17 kJ/mol. This discrepancy may result from experimental variables such as moisture measurement errors, increased internal resistance to water migration due to the fibrous nature of cassava peel, and possible physicochemical matrix transitions that hinder diffusion. Another factor contributing to the higher energy requirement is the occurrence of competing reactions during drying. By reevaluating Ea at various temperature intervals and excluding locations outside of the linear Arrhenius regime, a sensitivity analysis was carried out (results not shown). However, even with these adjustments, it was not possible to obtain lower values than those originally estimated, which reinforces the robustness of the result. Further studies comparing different drying conditions and plant matrices are recommended to clarify these deviations. These thermodynamic properties, primarily ΔH (kJ/mol), ΔS (J/mol·K), and ΔG (kJ/mol), have direct implications for scalability. The energy fluctuations occurring during sorption, as water molecules interact with product constituents, are quantified by changes in enthalpy (ΔH). Entropy (ΔG) is related to the spatial arrangement of the water-product and can be linked to the binding or repulsion of water molecules from food components in the system [41]. The degree of order or disorder in the water-product system is defined or characterized by entropy (ΔG). Conversely, Gibbs free energy provides a criterion for evaluating water desorption and reflects the product’s affinity for water. The energy required to transfer water molecules between the vapor state and a solid surface is associated with changes in Gibbs free energy during water exchange between the product and its environment [42]. 3.3. Analysis Performed at DCP After the drying process was completed, analyses of TPC, AA, and starch were performed in DCP, as shown in Figure 3a–c. The increase in temperature leads to the degradation of phenolic compounds (Figure 3a) and a decrease in AA (Figure 3b); therefore, to extract phenolic compounds from this residue, it is not advisable to work at temperatures above 60 °C.Determination

RCP

Variation Coefficient (%)

Moisture (g/100 g)

71.00 ± 0.32

1.04

Ash (g/100 g)

8.15 ± 0.41

4.58

Lipids (g/100 g)

0.29 ± 0.01

3.45

Proteins (g/100 g)

4.70 ± 0.05

1.22

Starch (g/100 g)

42.12 ± 0.40

0.95

aw

0.981 ± 0.01

1.01

TSS (ºBrix)

3.0 ± 0.01

0.33

TTA (NaOH 1 M/100 g)

4.13 ± 0.24

5.81

pH

5.06 ± 0.14

2.78

TPC (mg GAE/g)

12.50 ± 1.80

14.4

ABTS (µmol TE/g)

150.00 ± 18.33

12.22

Model

T (°C)

R2

SE

χ2

Logarithmic

50

0.99722

0.0189

3.5738.10−4

60

0.98261

0.4005

0.0016

70

0.97742

0.0418

0.0018

80

0.96563

0.0427

0.0018

Diffusion Approximation

50

0.9958

0.0232

5.40 × 10−4

60

0.9679

0.0550

0.0030

70

0.9824

0.0369

0.0013

80

0.9947

0.0612

2.8 × 10−4

Newton

50

0.9896

0.0364

0.0013

60

0.9667

0.0561

0.0031

70

0.9342

0.0713

0.0050

80

0.9518

0.0505

0.0025

Henderson & Pabis

50

0.9941

0.0274

0.0157

60

0.9676

0.0552

0.0641

70

0.9631

0.0534

0.0599

80

0.9567

0.0479

0.0482

Wang & Singh

50

0.9924

0.0312

9.7 × 10−4

60

0.7275

0.1604

0.0257

70

0.5911

0.1780

0.0316

80

-

-

-

Thermodynamic Properties

Temperature °C

50

60

70

80

K parameter

0.077

0.020

0.022

0.088

Deff x10−10 (m2/s)

0.649

1.435

1.320

5.842

ΔH (kJ/mol)

66.64

66.55

66.47

66.39

ΔS (J/mol.K)

−276.01

−269.42

−270.12

−257.76

ΔG (kJ/mol)

137.82

137.74

134.25

137.72

The physicochemical characterization confirmed the potential of cassava peel as a valuable by-product for the food industry. Studying its drying kinetics was essential for extending shelf life, reducing microbial susceptibility, and enabling broader applications. Among the mathematical models tested, the logarithmic model best described the drying behavior, while drying at 50 °C preserved phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity. Higher temperatures caused minimal starch losses, indicating their suitability for starch-focused applications. Although the study demonstrated the feasibility of drying cassava peel, it was limited to laboratory-scale hot air convection. Future research should address scale-up, evaluate alternative or hybrid drying technologies (e.g., vacuum, infrared, or freeze-drying), and investigate storage stability and practical applications to advance sustainable and efficient valorization strategies.

| aw | Water activity |

| DCP | Dry Cassava Peels |

| Deff | Effective diffusivity |

| Ea | activation energy |

| R | universal gas constant (8.314 kJ/mol.K) |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RCP | Cassava Peels |

| Ta | absolute temperature (K) |

| TPC | Total phenolic compounds |

| TSS | Total soluble solids |

| TTA | Total titratable acidity |

| χ2 | Chi-square |

| ∆H | Enthalpy variation (kJ/mol) |

| ∆S | Entropy variation (J/mol.K) |

| ∆G | Gibbs free energy (kJ/mol) |

Data curation, Investigation: B.A.S.R.; Investigation: C.H.L.M.; Writing—original draft: C.M.P.M.; Investigation: E.S.P.; Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft: A.C.B.F. Performed starch determination analyses and preliminary tests in choosing the condition for the kinetic study of drying. A.K.; Formal analysis, Writing—original draft: G.G.F.; Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, visualization: L.H.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data supporting the results of the current study are available within the article.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

The authors wish to thank FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas) research grant N° 2023/557732 for financial support.

The authors wish to thank Sirs Ricardo, Igor, and Chiquinho for laboratory support. Also, we thank Proped-UFRA for granting scholarships to scientific initiation students.

[1] Lobo, I.D.; Júnior CFdos, S.; Nunes, A. Importância Socioeconômica da Mandioca (Manihot esculenta Crantz) para a Comunidade de Jaçapetuba, Município de Cametá/PA. Multitemas 2018, 23, 195. [CrossRef]

[2] Farias, A.R.N.; Mattos, P.; Fukuda, W. Processamento e utilização da mandioca. Cruz das Almas: Embrapa Mandioca e Fruticultura Tropical, 45-547. 2005. Available online: http://livimagens.sct.embrapa.br/amostras/00076810.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

[3] Cruz, I.A.; Andrade, L.R.S.; Bharagava, R.N.; Nadda, A.K.; Bilal, M.; Figueiredo, R.T.; Ferreira, L.F.R. Valorization of Cassava Residues for Biogas Production in Brazil Based on the Circular Economy: An Updated and Comprehensive Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100196. [CrossRef]

[4] Olmedo, J.Z.R.; Da Silva, T.A.; Da Silva, S.A.; De Lima, C.S.; Matsumoto, N.K.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Queiroz, I.M.; De Conti, A.C. Análise Preliminar do Potencial Energético da Casca de Mandioca para Formação de Biochar. Eng. Technol. Sci. J. 2023, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

[5] Napasirth, V.; Napasirth, P.; Sulinthone, T.; Phommachanh, K.; Cai, Y. Microbial population, chemical composition and silage fermentation of cassava residues. Anim. Sci. J. 2015, 86, 842–848. [CrossRef]

[6] de Campos Cuchi, M.M.; Galão, O.F. Obtenção de Etanol a Partir de Resíduos de Mandioca (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Semin. Ciências Exatas Tecnol. 2022, 43, 85–94. [CrossRef]

[7] Goncalves, J.A.G.; Zambom, M.A.; Fernandes, T.; Mesquita, E.E.; Schimidt, E.; Javorski, C.R.; Dalazencastagnara, D. Chemical Composition and Profile of the Fermentation of Cassava Starch By-Products Silage. Orig. Artic. Biosci. J. 2014, 30, 502–511. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289266397_Chemical_composition_and_profile_of_the_fermentation_of_cassava_starch_by-products_silage

[8] Vilhalva, D.A.A.; Soares Júnior, M.S.; Caliari, M.; da Silva, F.A. Secagem Convencional de Casca de Mandioca Proveniente de Resíduos de Indústria de Amido. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2012, 42, 331–339. [CrossRef]

[9] Barros, S.L.; Câmara, G.B.; de Farias Leite, D.D.; Santos, N.C.; dos Santos, F.S.; da Cunha Soares, T.; Lima, A.R.N.; Oliveira, M.N.; Vasconcelos, U.A.A.; et al. Modelagem Matemática da Cinética de Secagem de Cascas do Kino (Cucumis metuliferus). Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e60911608. [CrossRef]

[10] Lopes De Menezes, M.; Ströher, A.P.; Pereira, N.C.; Davantel De Barros, S.T. Análise da Cinética e Ajustes de Modelos Matemáticos aos Dados de Secagem do Bagaço do Maracujá-Amarelo. Rev. Engevista 2013, 15, 176–186. [CrossRef]

[11] IAL. Normas Analíticas do Instituto Lutz: Vol. 1 IAL: São Paulo, Brazil, 1985; Available online: https://wp.ufpel.edu.br/nutricaobromatologia/files/2013/07/NormasADOLFOLUTZ.pdf

[12] Azzini, A.; Arruda, M.C.Q. Sacarificação da Serragem de Bambu Visando ao Estabelecimento de um Método de Determinação de Amido. Bragantia 1986, 45, 15–22. [CrossRef]

[13] Guindani, M.; Tonet, F.; Kuhn, F.; MAGRO, J.; Dalcanton, F.; Fiori, M.A.; Mello, J.M.M. Estudo do Processo de Extração dos Compostos Fenólicos e Antocianinas Totais do Hibiscus Sabdariffa. In Anais do XX Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia Química; Editora Edgard Blücher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; 4496–4502. [CrossRef]

[14] Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [CrossRef]

[15] Rufino, M.S.; Alves, R.E.; Fernandes, F.A.; Brito, E.S. Free Radical Scavenging Behavior of Ten Exotic Tropical Fruits Extracts. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2072–2075. [CrossRef]

[16] Martins, M.G.; Pena, R.D.S. Combined Osmotic Dehydration and Drying Process of Pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) Fillets. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3170–3179. [CrossRef]

[17] Kosasih, E.A.; Zikri, A.; Dzaky, M.I. Effects of Drying Temperature, Airflow, and Cut Segment on Drying Rate and Activation Energy of Elephant Cassava. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020, 19, 100633. [CrossRef]

[18] Goneli, A.L.D.; do Carmo Vieira, M.; da Cruz Benitez Vilhasanti, H.; Gonçalves, A.A. Modelagem Matemática e Difusividade Efetiva de Folhas de Aroeira durante a Secagem. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2014, 44, 56–64. [CrossRef]

[19] Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1975; vol. 1; 21–24. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www-eng.lbl.gov/~shuman/NEXT/MATERIALS%26COMPONENTS/Xe_damage/Crank-The-Mathematics-of-Diffusion.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjYjufc-e2PAxX8k1YBHYLWD7sQFnoECCYQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1JzzIv-HQia07ux9L948nt (accessed on 31 July 2025).

[20] Toğrul, İ.T.; Pehlivan, D. Mathematical Modelling of Solar Drying of Apricots in Thin Layers. J. Food Eng. 2002, 55, 209–216. [CrossRef]

[21] Corrêa, P.C.; Oliveira, G.H.H.; Botelho, F.M.; Goneli, A.L.D.; Carvalho, F.M. Modelagem Matemática e Determinação das Propriedades Termodinâmicas do Café (Coffea arabica L.) durante o Processo de Secagem. Rev. Ceres 2010, 57, 595–601. [CrossRef]

[22] De Faria, R.Q.; Teixeira, I.R.; Devilla, I.A.; Ascheri, D.P.R.; Resende, O. Cinética de Secagem de Sementes de Crambe. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2012, 16, 573–583. [CrossRef]

[23] Henderson, S.M.; Pabis, S. Grain Drying Theory. 1. Temperature Effect on Drying Coefficient. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1961, 6, 169–164. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19621700719 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

[24] Wang, C.Y.; Singh, R.P. Use of Variable Equilibrium Moisture Content in Modeling Rice Drying. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1978, 11, 668–672. Available online: https://jglobal.jst.go.jp/en/detail?JGLOBAL_ID=201002003579923786 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

[25] Silva, H.W.; Rodovalho, R.S.; Velasco, M.F.; Silva, C.F.; Vale, L.S.R. Kinetics and Thermodynamic Properties Related to the Drying of ‘Cabacinha’ Pepper Fruits. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agricola E Ambient. 2016, 20, 174–180. [CrossRef]

[26] Tapia, M.S.; Alzamora, S.M.; Chirife, J. Effects of Water Activity (aw) on Microbial Stability as a Hurdle in Food Preservation. In Water Activity in Foods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 323–355. [CrossRef]

[27] Souto, L.R.F. Utilização do Amido da Casca de Mandioca na Produção de Vinagre: Características Físico-Químicas e Funcionais Universidade Federal de Goiás: Goiás, Brazil, 2011; Available online: https://academicoo.com/tese-dissertacao/utilizacao-do-amido-da-casca-de-mandioca-na-producao-de-vinagre-caracteristicas-fisico-quimicas-e-funcionais-use-of-starch-from-cassava-peel-in-the-production-of-vinegar-physicochemical-and-functional-characteristics (accessed on 31 May 2025).

[28] Batista Pinheiro, S.; et al. Caracterização Físico-Química e Análise de Compostos Fenólicos em Cascas de Mandioca in natura e Submetidas a Tratamento Hidrotérmico. In Anais do II Conecta UFRA: Bioeconomia; 2022; Available online: https://www.even3.com.br/anais/ii-conecta-ufra-bioeconomia-268119/566019-caracterizacao-fisico-quimica-e-analise-de-compostos-fenolicos-em-cascas-de-mandioca-in-natura-e-submetidas-atrat

[29] Pinto, C.C.; Amorim, M.T.; da Cunha, R.G.; Amaro, B.O.; de Melo Oliveira, S.R.; Pinheiro, M.D.C.N.; da Silva Costa, E.D.S.; de Oliveira, C.S.B. Parâmetros Físico Químicos e Resíduos Cianogênicos em Farinhas de Mandioca de Diferentes Casas de um Município do Estado do Pará, Brasil. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 43459–43473. [CrossRef]

[30] Biondi, F.; Balducci, F.; Capocasa, F.; Visciglio, M.; Mei, E.; Vagnoni, M.; Mezzetti, B.; Mazzoni, L. Environmental Conditions and Agronomical Factors Influencing the Levels of Phytochemicals in Brassica Vegetables Responsible for Nutritional and Sensorial Properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1927. [CrossRef]

[31] Santos, M.A.I.; Simão, A.A.; Marques, T.R.; Sackz, A.A.; Corrêa, A.D. Efeito de Diferentes Métodos de Extração sobre a Atividade Antioxidante e o Perfil de Compostos Fenólicos da Folha de Mandioca. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2016, 19 [CrossRef]

[32] Madamba, P.; Driscoll, R.; Buckle, K. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation Models for Sorption and Browning of Garlic. J. Food Eng. 1996, 28, 109–119. [CrossRef]

[33] Draper, N.R.; Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Vol. 1;. [CrossRef]

[34] Lima, N.C.R.; Junior, J.M.D.S.; Filho, E.E.X.G.; Costa, R.M.M.; Santana, A.A. Cinética de Secagem e Difusividade Efetiva do Abiu (Pouteria caimito)/Abiu (Pouteria caimito) Drying and Effective Diffusivity Kinesy. Braz. Appl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 5, 2–10. [CrossRef]

[35] Modesto Junior, E.N.; Carmo, J.R.; Chisté, R.C.; Pena, R.S. Cinética de Secagem das Folhas de Mandioca (Manihot esculenta Crantz). In XXVI Congresso Brasileiro de Ciência dos Alimentos; CBCTA: Belém, PA, Brazil, 2018.

[36] Oliveira, G.H.H.; Aragão, D.M.S.; de Oliveira, A.P.L.R.; Silva, M.G.; Gusmão, A.C.A. Modelagem e Propriedades Termodinâmicas na Secagem de Morangos. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2015, 18, 314–321. [CrossRef]

[37] Cuevas, M.; Martínez-Cartas, M.L.; Pérez-Villarejo, L.; Hernández, L.; García-Martín, J.F.; Sánchez, S. Drying Kinetics and Effective Water Diffusivities in Olive Stone and Olive-Tree Pruning. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 911–920. [CrossRef]

[38] Santos, D.D.C.; Costa, T.N.D.; Franco, F.B.; Castro, R.D.C.; Ferreira, J.P.D.L.; Souza, M.A.D.S.; Santos, J.C.P. Cinética de Secagem e Propriedades Termodinâmicas da Polpa de Patauá (Oenocarpus bataua Mart.). Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22, e2018305. [CrossRef]

[39] Jideani, V.; Mpotokwana, S. Modeling of Water Absorption of Botswana Bambara Varieties Using Peleg’s Equation. J. Food Eng. 2009, 92, 182–188. [CrossRef]

[40] Kayacier, A.; Singh, R.K. Application of Effective Diffusivity Approach for the Moisture Content Prediction of Tortilla Chips during Baking. LWT 2004, 37, 275–281. [CrossRef]

[41] Morais SJda, S.; Devilla, I.A.; Ferreira, D.A.; Teixeira, I.R. Modelagem Matemática das Curvas de Secagem e Coeficiente de Difusão de Grãos de Feijão-Caupi (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.). Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2013, 44, 455–463. [CrossRef]

[42] de Oliveira, G.H.H.; Corrêa, P.C.; Santos, E.D.S.; Treto, P.C.; Diniz, M.D.M.S. Evaluation of Thermodynamic Properties Using GAB Model to Describe the Desorption Process of Cocoa Beans. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 2077–2084. [CrossRef]

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more