APA Style

Soumi Das. (2025). Unraveling Conformational Thermodynamics of Ligand Binding to Fluoride Riboswitch Aptamer: Implications for Therapeutic Design. Molecular Modeling Connect, 2 (Article ID: 0012). https://doi.org/10.69709/MolModC.2025.170203MLA Style

Soumi Das. "Unraveling Conformational Thermodynamics of Ligand Binding to Fluoride Riboswitch Aptamer: Implications for Therapeutic Design". Molecular Modeling Connect, vol. 2, 2025, Article ID: 0012, https://doi.org/10.69709/MolModC.2025.170203.Chicago Style

Soumi Das. 2025. "Unraveling Conformational Thermodynamics of Ligand Binding to Fluoride Riboswitch Aptamer: Implications for Therapeutic Design." Molecular Modeling Connect 2 (2025): 0012. https://doi.org/10.69709/MolModC.2025.170203.

ACCESS

Research Article

ACCESS

Research Article

Volume 2, Article ID: 2025.0012

Soumi Das

soumi.das@bose.res.in

Department of Physics of Complex Systems, S.N. Bose National Center for Basic Sciences, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700106, India

Received: 13 Jun 2025 Accepted: 08 Oct 2025 Available Online: 09 Oct 2025 Published: 30 Oct 2025

Riboswitches are structured, non-coding mRNA segments in which the binding of a ligand to an aptamer domain triggers conformational changes in a downstream expression platform, thereby regulating gene expression and establishing them as attractive targets for antimicrobial therapy. The fluoride riboswitch, present in several pathogenic bacteria, represents a promising but underexplored therapeutic target, as it plays a key role in bacterial defense through fluoride ion (F−) binding facilitated by Mg2+. In this study, we investigate the conformational stability of (i) the holo form of the Thermotoga petrophila fluoride riboswitch aptamer (RNA in the presence of F− + Mg2+ + K+) relative to (ii) the apo form (RNA in the absence of F− + Mg2+ + K+). Conformational thermodynamic analysis reveals that the holo riboswitch is stabilized at the ion-recognition site, the pseudoknot, and Stem 1, whereas Stem 2, Loop 1, Loop 2, and most unpaired nucleotides are more disordered and destabilized. Complementary docking studies identify these destabilized regions as putative binding pockets for non-cognate ligands. Together, these findings provide structural and thermodynamic insights into fluoride riboswitch–ligand interactions, guiding the design of nucleic acid–targeted therapeutics, including RNA-modulating drugs and engineered aptamers. Future in vitro and in vivo validation will be critical for translating these computational predictions into novel strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Conformational stability of (i) the holo form of T. Petrophila fluoride riboswitch aptamer (RNA + F− + Mg2+ + K+) with respect to (ii) the apo form of fluoride riboswitch (RNA in the absence of F− + Mg2+ + K+) is studied using molecular dynamics simulation. Holo Fluoride riboswitch aptamer gets energetically and entropically stable at Pseudoknot, Stem1, and Ion recognition sites, whereas Stem2, Loop1, Loop2, and most of the unpaired bases show significant disorder and destabilization. The hydrogen-bond network for the pseudoknot, Stem 1, and Stem 2 in the apo fluoride riboswitch is significantly weaker. Molecular Docking study confirms that the thermodynamically destabilized and disordered residues in Stem2 and Loop1 of the holo fluoride riboswitch aptamer may act as potential binding sites for non-cognate ligands.

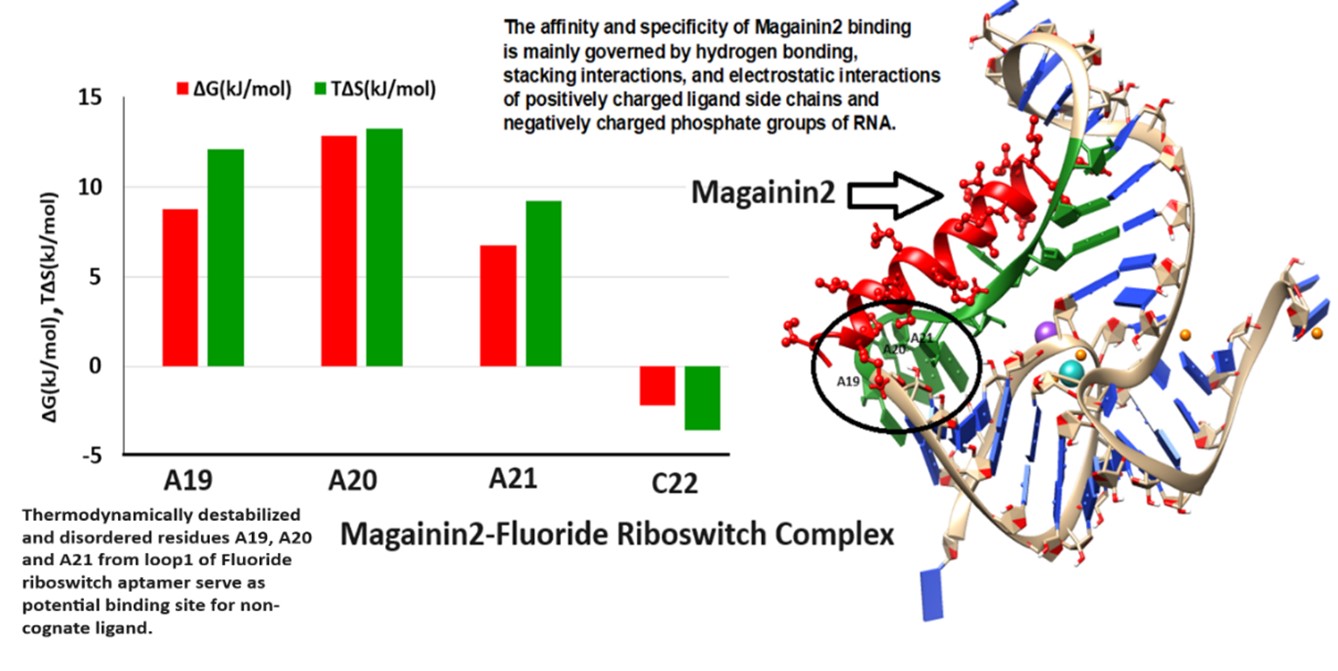

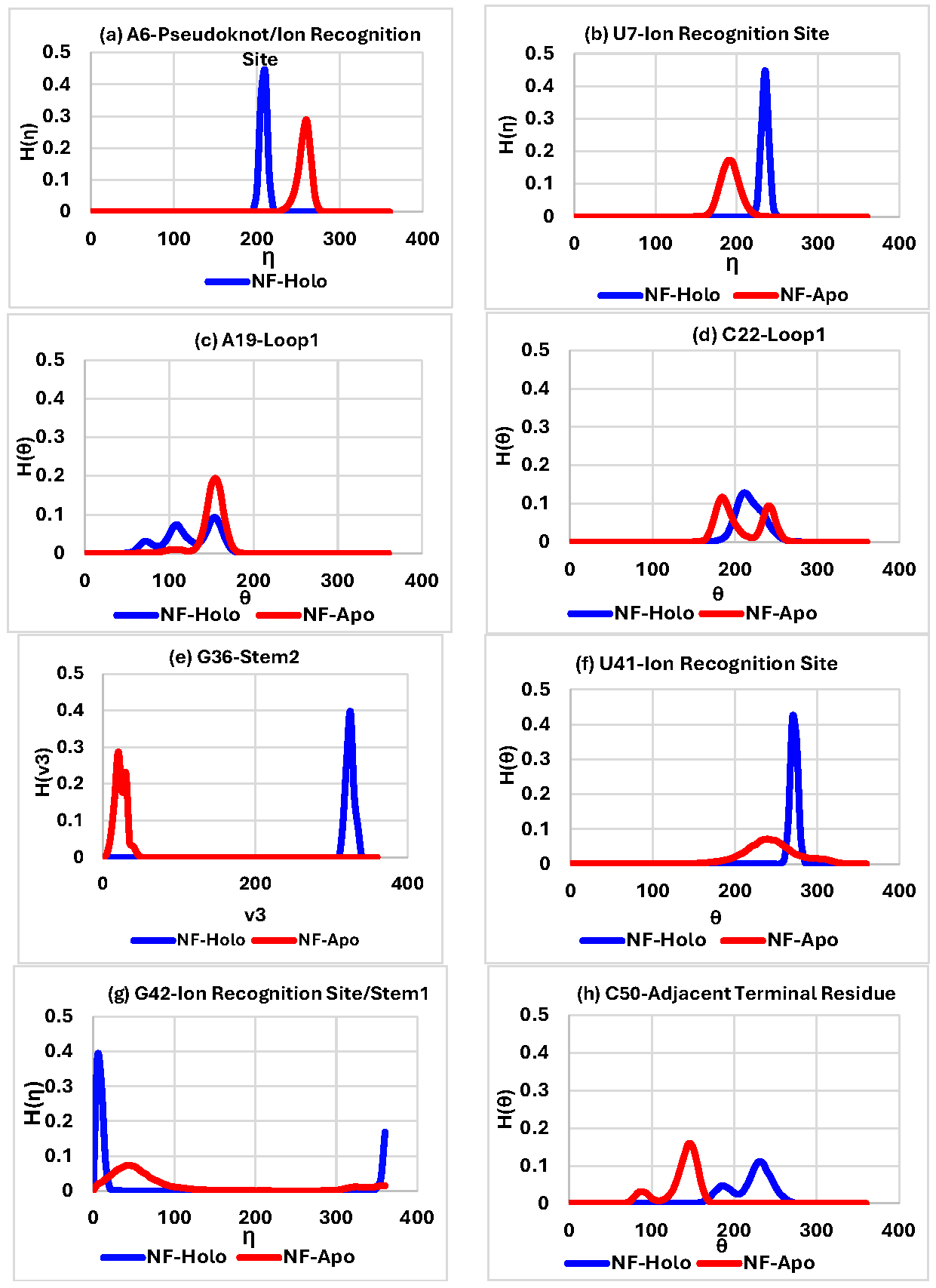

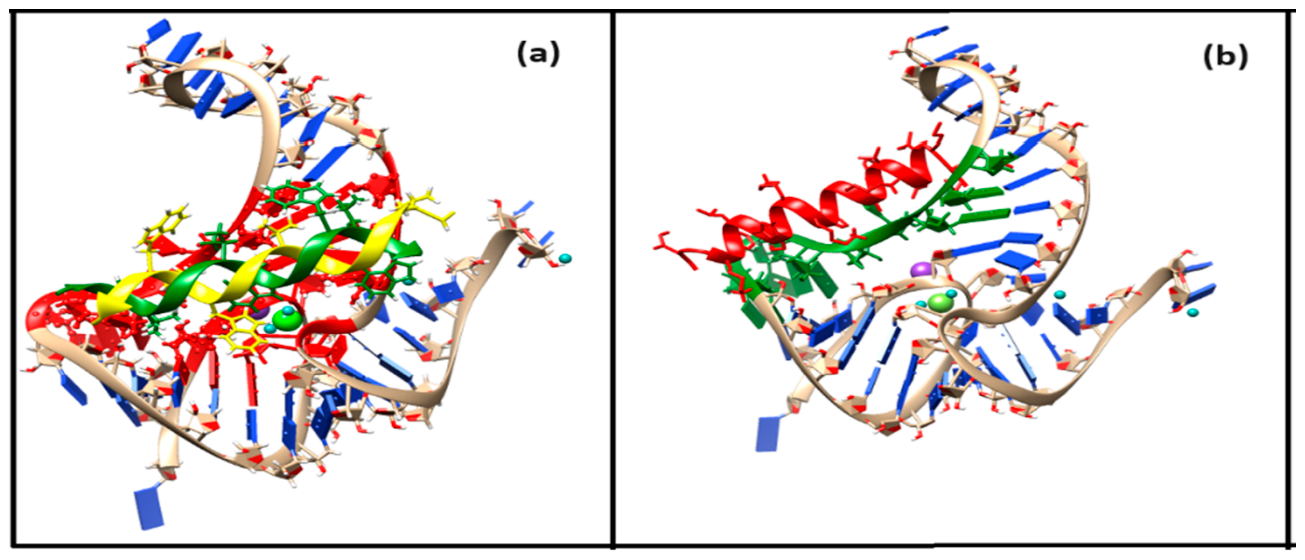

Protein–nucleic acid complexes, once considered “undruggable,” can now be therapeutically modulated by stabilizing specific conformations, allosterically reshaping interactions, directly disrupting protein–nucleic acid binding, or selectively degrading interaction partners, enabling small molecules or engineered peptides to regulate complex function effectively. Many cellular and viral RNAs fold into higher-order architectures featuring grooves, clefts, multi-helix junctional hubs, and dynamically allosteric motifs that generate well-defined binding pockets analogous to those exploited in protein–DNA complexes and amenable to selective engagement by small molecules or peptides. Recent advances in RNA biology have reinforced RNA’s role as a central regulator of gene expression and highlighted its versatility as a dynamic drug target, thereby expanding the chemical and structural landscape for nucleic-acid–focused pharmacology [1,2,3]. Riboswitches are structured RNA elements, typically located in the 5′ untranslated regions of bacterial mRNAs, which regulate gene expression through direct recognition of small-molecule ligands. Ligand binding to the aptamer domain triggers conformational changes in the expression platform through conformational selection and induced-fit mechanisms, thereby enabling regulation at the levels of transcription, translation, mRNA stability, and, in some cases, splicing, all without the participation of protein cofactors. Riboswitches’ high specificity, absence in humans, and central roles in essential bacterial pathways—such as coenzyme biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism—make them highly attractive drug targets. Riboswitch-targeted drug design follows three main strategies: (i) developing synthetic analogs that mimic natural ligands to modulate riboswitch activity, (ii) designing ligands that lock the riboswitch in an inactive conformation to block gene regulation, and (iii) employing small molecules or engineered modulators that either block ligand binding or disrupt the communication between the aptamer and expression platform, thereby inhibiting riboswitch activity. Such approaches not only impair bacterial survival but also provide mechanisms distinct from protein-targeting antibiotics, offering substantial potential to overcome existing bacterial resistance pathways [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Riboswitches achieve precise metabolite recognition and regulatory switching through an intricate interplay of conserved secondary-structure motifs and stabilizing tertiary contacts. In the thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) riboswitch, helices P1–P5 and internal loops form the ligand-binding junction, while coaxial stacking and loop–loop interactions stabilize the pyrophosphate pocket. Purine riboswitches use a streamlined architecture in which the P1 helix serves as the genetic switch, while bulged residues in P2–P3 define the purine-binding pocket, reinforced by kissing-loop contacts and base triples. A-rich loops and helical scaffolds orient the ligand, while base triples and aromatic stacking stabilize the isoalloxazine ring in the flavin mononucleotide (FMN) riboswitch. The fluoride riboswitch integrates a pseudoknot stem with Mg2+ mediated tertiary contacts to stabilize an anion-binding pocket, and the SAM-I riboswitch uses a four-way junction, internal asymmetries, and tertiary A-minor interactions to enclose its sulfonium center. In the glycine riboswitch, long-range loop–loop interactions bridge separate aptamer domains, enabling cooperative binding across two glycine sites. Across various riboswitch classes—including FMN, B12 (cobalamin), and THI-box riboswitches—T-loop motifs act as conserved structural elements that mediate long-range tertiary interactions crucial for ligand recognition and overall riboswitch functionality. Collectively, these examples illustrate a unifying principle of riboswitch biology: secondary elements such as helices, bulges, and pseudoknots provide the structural scaffold, while tertiary interactions—including loop–loop docking, base triples, and metal-mediated contacts—refine the architecture and confer the ligand specificity and precise regulatory control that define riboswitch function. Dedicated databases are increasingly central to riboswitch research, integrating sequence, structural, and functional information across diverse classes. RiboCenter-switch compiles over 89,000 sequences from 56 riboswitch families and orphan candidates, integrating experimentally validated structural data with ligand-binding information and comparative visualization tools. By unifying natural and orphan riboswitches, the platform enables evolutionary analyses, functional annotation, and mechanistic studies. Such resources not only accelerate riboswitch discovery but also provide a foundation for exploiting RNA-based regulatory elements in synthetic biology and biotechnology. To date, over 55 riboswitch classes have been identified, recognizing diverse ligands ranging from coenzymes (e.g., FMN, TPP, SAM, NAD+), sugars (e.g., glucosamine-6-phosphate), nucleobases and their derivatives (e.g., adenine, guanine, xanthine and prequeuosine1), and amino acids (e.g., glycine, lysine), to signaling molecules (e.g., cyclic AMP-GMP and cyclic di-GMP) and simple ions such as Mn2+, Mg2+, and F−. Although traditionally viewed as small-molecule sensors, riboswitches can also recognize larger ligands such as tRNAs, as seen in T-box riboswitches, which engage their cognate tRNA at multiple distant sites through diverse RNA–RNA interactions. In addition to gene regulation, some riboswitches function as ribozymes, as exemplified by the glmS riboswitch, which undergoes self-cleavage upon binding glucosamine-6-phosphate, thereby directly linking metabolite sensing with mRNA degradation. Metalloriboswitches constitute a subclass of riboswitches that detect specific metal ions and regulate genes associated with metal transport, homeostasis, and detoxification. By binding their cognate ions, these RNAs undergo conformational changes that control transcription or translation, thereby maintaining essential yet potentially toxic metals at optimal levels. Representative examples include the manganese riboswitch (ykoY family) in Bacillus subtilis, which balances Mn2+ uptake, the nickel–cobalt riboswitch that activates efflux pumps to prevent Ni2+ and Co2+ toxicity, and the magnesium riboswitch in Salmonella enterica, which modulates the mgtA transporter. Although it is not a metal sensor, the fluoride riboswitch is often grouped with them due to its function in controlling anion efflux under toxic conditions. Beyond their physiological importance, metalloriboswitches hold promise as antibacterial drug targets, since disrupting their function perturbs metal balance, and act as biosensors, owing to their natural selectivity for metal ions. The fluoride riboswitch exemplifies RNA–anion recognition, where three Mg2+ ions selectively chelate the highly electronegative F− ion, as illustrated in Figure 1a,b,c. This riboswitch maintains cytoplasmic fluoride levels below toxic thresholds and, due to its presence in several human pathogens, represents a potential antimicrobial target. Remarkably, among halides, only F− exhibits strong specificity for the aptamer. The fluoride riboswitch achieves exceptional F− selectivity through a unique metal-mediated coordination, where three Mg2+ ions, octahedrally coordinated with water and inward-facing RNA phosphate oxygens, form an electrostatic cage that stabilizes the weakly hydrated anion. This coordination triggers conformational changes in the aptamer that propagate to the expression platform, coupling fluoride recognition to gene regulation. In Bacillus cereus, the riboswitch controls transcription termination, whereas in Pseudomonas syringae it regulates translation initiation, activating genes that encode fluoride transporters (e.g., CrcB) and resistance enzymes to maintain cellular homeostasis. Fluoride binding stabilizes a pseudoknot that prevents terminator formation, whereas its absence promotes terminator hairpin formation, creating an Mg2+ -assisted two-step switching mechanism central to regulatory function. Through this coupling of coordination chemistry and RNA folding, the riboswitch links selective fluoride recognition to transcriptional or translational regulation. Fluoride riboswitches have emerged as highly sensitive and selective biosensors, capable of detecting fluoride ions (F−) through conformational changes coupled to measurable outputs such as fluorescence or colorimetric signals. This approach offers cost-effective alternatives to conventional detection methods, enabling rapid water quality monitoring. Beyond their biomedical applications, fluoride riboswitches are valuable tools for environmental monitoring and for investigating co-transcriptional folding, RNA–ligand interactions, and mechanisms of gene regulation. More broadly, riboswitches are versatile RNA regulators with expanding roles in biosensing and biotherapy, including food safety, metabolic engineering, live-cell imaging, and antibacterial drug discovery [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Riboswitches control bacterial ion homeostasis by sensing metabolites or ions and regulating gene expression. The fluoride riboswitch aptamer encapsulates F− via three Mg2+ ions, but the assembly mechanism remains unclear. Using multiscale RNA simulations, Kumar et al. (2023) showed that two Mg2+ ions initially coordinate Ligand Binding Domain (LBD) phosphates through water-mediated outer-shell interactions before forming dehydrated inner-shell contacts to stabilize the domain. The third Mg2+ ion and fluoride bind cooperatively as a water-mediated ion pair, reducing electrostatic repulsion. Stability arises from a finely balanced network of five phosphates, three Mg2+ ions, and solvated fluoride, which reveals a stepwise assembly mechanism and guides the design of RNA-based ion sensors and molecular logic devices [12]. Density functional theory (DFT) has elucidated how the Mg2+/fluoride/phosphate/water cluster at the center of the fluoride riboswitch contributes to its stability and specificity (Chawla et al., 2015) [13]. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations have been utilized to investigate the folding pathways and conformational changes of the riboswitch in response to ligand binding. These computational insights have complemented experimental findings, such as those from single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) studies, which have revealed the dynamic folding transitions of the Bacillus cereus fluoride riboswitch in the presence of fluoride ions. In the fluoride riboswitch, transcriptional repression is driven by a transient excited state (ES). Using 180 μs of molecular dynamics simulations, Hu et al. (2024) mapped the ES ensemble. They uncovered a signaling pathway linking the Mg2+/F− binding pocket to the regulatory A40–U48 pair via U7–G8 phosphate interactions and a G8–C47–U48 nucleobase network. These results provide structural insight into ligand-sensing dynamics and reveal how a holo-like apo conformation primes transcription termination [14]. Collectively, these computational approaches have provided a detailed mechanistic understanding of how fluoride riboswitches function as molecular sensors and regulators, paving the way for their application in synthetic biology and therapeutic development. Experimental studies using SHAPE-seq, CEST-NMR, and smFRET on the Bacillus cereus crcB fluoride riboswitch highlight aptamer stability across different ion states [19,20]. Despite the availability of its experimental structure, the detailed structural and thermodynamic mechanisms of ligand binding remain unresolved. Standard techniques such as Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) directly measure the overall thermodynamics of ligand binding, enabling precise determination of key parameters such as binding affinity (Ka), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy change (ΔH), and entropy change (ΔS), but lack residue-specific insight. To address this gap, we evaluated the domain-wise and residue-specific conformational stability of the holo fluoride riboswitch relative to the apo form using a histogram-based thermodynamics approach derived from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. This methodology, previously applied to proteins [21,22,23,24,25,26] and protein–DNA complexes [27,28], is extended here to RNA [29]. We quantify RNA conformational variables including (i) inter-base pair step parameters (tilt τ, roll ρ, twist ω, shift Dx, slide Dy, rise Dz), (ii) intra-base pair parameters (buckle κ, open σ, propeller π, stagger Sx, shear Sy, stretch Sz), (iii) sugar-phosphate backbone torsions (α, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ) and χ, (iv) sugar pucker (ν0–ν4), and (v) pseudo-torsions (η, θ). Negative changes in conformational free energy and entropy indicate structural stabilization and increased ordering, whereas positive changes signify destabilization and disorder. The RNA conformational parameters are detailed in the Supplementary Information. Simulating the full expression platform remains challenging due to its intrinsic flexibility and lack of crystallographic data. Ligand removal (F−, Mg2+, K+) induces notable phosphate backbone distortions near the binding pocket, as revealed by fluctuations in microscopic conformational variables. It is hypothesized that thermodynamically destabilized and disordered residues serve as additional ligand-binding sites, thereby decreasing the system’s free energy and entropy. Our analyses show that the ion recognition site, pseudoknot, and stem1 are strongly stabilized upon ligand binding, while loop1, loop2, and stem2 become destabilized and disordered. In particular, destabilized regions of stem2 and loop2 may serve as potential sites for non-cognate ligands. Docking studies with the antibiotics Gramicidin D and Magainin2 support this hypothesis, showing that these ligands preferentially bind to the disordered loop1 and stem2 regions. Overall, our findings reveal residue-wise and domain-wise conformational thermodynamics govern fluoride riboswitch–ligand interactions. This approach can be generalized to investigate non-cognate ligand binding across riboswitches, offering a framework to guide nucleic acid–targeted therapeutic design.

2.1. System Preparations The holo T. petrophila fluoride riboswitch aptamer structure was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 4ENC). To construct the apo state, bound fluoride (F−), magnesium (Mg2+), and potassium (K+) ions were removed from the crystallographic coordinates. Two cases of the aptamer were modeled, as shown in Table 1: Summary of molecular dynamics simulation parameters and structural stability (RMSD) of holo and apo. 2.2. Simulation Details All MD simulations were performed using GROMACS [30] with χOL3 RNA force-field parameters [31]. For explicit-solvent calculations, the systems were solvated in a cubic box with a 15 Å buffer of water and neutralized by adding Na+ and Cl− ions. The periodic boundary conditions were imposed in all directions. Subsequently, the systems were energy-minimized using the steepest descent algorithm [32]. Particle Mesh Ewald summation (PME) is used for long-ranged electrostatic interactions with a 1 Å grid spacing and a 10−6 convergence criterion. The Lennard-Jones and the short-range electrostatic interactions were truncated at 10 Å. The all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is carried out at 300 K temperature and atmospheric pressure in an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble starting from the energy minimized structure. The Berendsen thermostat [33] is used to maintain a constant temperature, and the pressure is controlled by the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [34]. The LINCS constraints were applied to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms. An integration time step of 1 fs was used. We performed 1 μs MD simulations for the holo and apo fluoride riboswitch aptamer with a duration of 1 µs. Trajectories were visualized in VMD, and figures prepared with UCSF Chimera [35] and PyMOL [36]. 2.3. Structural Analysis Equilibration was assessed using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). The backbone phosphorus (P) atom–based root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) per residue was calculated to further analyze the flexibility of each nucleotide and to compare the differences in dynamics between the unliganded and liganded simulations. Inter- and intra-base-pair parameters, torsion angles, pseudotorsion angles, and stacking overlap were calculated using NUPARM software [37]. Base pairing information was detected by BPFIND [38]. 2.4. Identification of Interactions The interactions were characterized by distance and angle criteria. Hydrogen bonds were considered present when the donor–acceptor distance was ≤ 3.5Å. The angle (D-H-A) cut-off was 160 °. The GROMACS Hydrogen bond analysis module was used for hydrogen bond network calculation. Electrostatic interactions were flagged when the distance between oppositely charged atoms was < 5.6 Å. 2.5. Conformational Thermodynamics The detailed description of the histogram-based method (HBM) for calculating the conformational thermodynamics is reported [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Histograms represent the probability distribution of observing a given conformation. Histogram peaks were related to effective free energies via Boltzmann factors. At the same time, the entropy is estimated according to the Gibbs formula. The conformational thermodynamics and the histograms are interconnected in this way. The computations are done using the code in https://github.com/snbsoftmatter/confthermo (accessed on 1 September 2022) [21,22,23,28,39,40]. Histograms were computed from the equilibrated trajectory segment (600–1000 ns). The normalized probability distribution of any microscopic conformational variable θ in the free state and the complex state is given by Hfree (θ) and Hcomplex (θ), respectively. The change in free energy of any microscopic conformational variable θ of the bound state as compared to the free state is defined as, The change in conformational entropy of a given microscopic conformational variable θ of the bound state as compared to the free state is evaluated as, 2.6. Docking Studies The average structure of the holo Fluoride riboswitch, calculated from the equilibrated MD trajectory, is used as the receptor for the docking procedure, while the peptide drugs Gramicidin D and Magainin 2 serve as ligands. Coordinates for Gramicidin D were retrieved from PDB ID: 1BDW, and those for Magainin 2 from PDB ID: 2MAG. The coordinates of Magainin 2 are segregated from PDB-ID: 2MAG. First, the HDOCK web server [41] (specialized for protein–protein and protein–nucleic-acid interactions) was used. Next, HADDOCK [42] is used to compare the docking scores between two structures for two cases. The docking protocol encompasses three stages, namely rigid body energy minimization, semi-flexible simulated annealing in torsion angle space, and explicit solvent refinement. Docking was biased by defining destabilized, disordered residues in Loop 1 and Stem 2 of the fluoride riboswitch aptamer as active binding residues. Minimum-energy criteria and RMSD-based clustering were used to sort docked structures. The central structure of the cluster with the maximum z-score is selected as the best docked structure. The complex interface was then analyzed using a 5 Å distance cutoff between residues of the binding partners. Docked complexes were further minimized in explicit solvent using the steepest-descent algorithm until the maximum force on any atom was < 100 kJ mol−1 nm−1, employing the AMBER ff14SB protein force field for peptides and χOL3 force-field parameters for RNA.

System

Duration of the Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Force Field

RMSD

(Mean and SD)

Holo form of fluoride riboswitch

(PDB-ID: 4ENC)

(RNA + F− + Mg2+ + K+)1 µs

χOL3 RNA Force field

3.98 Å (0.05)

Apo form of fluoride riboswitch

(Without F− + Mg2+ + K+)1 µs

χOL3 RNA Force field

4.1 Å (0.07)

The equilibrated snapshots of the holo and apo fluoride riboswitch at 1000 ns are shown in Figure 2a and Figure 2b, respectively. RMSDs of both the holo and apo structures (Figure S1a) are within an acceptable range; the average RMSD is 4.10 Å for the ligand-free apo structure and 3.98 Å for the ligand-bound holo structure. Domain/Region-wise RMSD analysis revealed that the Fluoride riboswitch aptamer exhibited distinct structural flexibility, summarized in Table S1a. The equilibrated part of the trajectory (600–1000 ns) was considered for further analysis. 3.1. Global and Local Dynamics of the Aptamer Domain and Interaction The stem1, stem2, pseudoknot, and ligand recognition sites show lower fluctuations for both ligand-free and ligand-bound simulations, as reflected from root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) (Figure S1b). Fluctuations in loop1 (residues 18, 19, 20, 21, 22), loop2 (29, 30, 31, 32), and terminal regions (49, 50, 51, 52) are generally higher than in the other areas of the aptamer. The intrinsic mobility of the terminal regions results in relatively higher fluctuations. The fluctuations become more pronounced in apo form with a sharp peak indicating a highly dynamic and flexible loop region. Fluctuations are the least in the ion binding sites (residues 5, 6, 7, 40, 41, 42). On a local scale, local conformational rearrangements in the loop region are manifested by higher RMSF values. Table S1b compares the probabilities of hydrogen bond interactions within the pseudoknot, stem 1, and stem 2 regions between the holo and apo systems. Donor-acceptor distance and the donor-hydrogen-acceptor angle cut-off are set as 3.4 Å and 120° respectively. Hydrogen bond probabilities PHB > 80% represent Strong (s) hydrogen bonds, while 40% < PHB < 80% correspond to Weak (w) hydrogen bonds. The number of Hydrogen bonds is higher in the holo form compared to the apo form. We found that the presence of Mg2+ and F− significantly enhances nearly all Watson–Crick base-pair hydrogen-bonding interactions in the pseudoknot and stem 1 regions of the holo form. F− ligand binding to the aptamer domain imposes stabilization of the pseudoknot and inhibits the formation of the terminator hairpin, leading to the transcription of the downstream gene (ON state). On the other hand, weak hydrogen bonds are observed in the holo and apo form of stem2. Watson–Crick base pairing in the pseudoknot and Stem 1 is frequently disrupted in the apo form due to formation of a transcription terminator (OFF state) involving a stable stem-loop. A conformational change of the Fluoride riboswitch aptamer occurs in the absence of the cognate ligand F−. Hydrogen bond analysis thus confirms that the aptamer domain and expression platform of the T. Petrophila Fluoride riboswitch interconvert between two conformations. The ligand-binding site coordination sphere in the holo system was analyzed in terms of bond lengths (Table S1c; Figures S2–S5).It is observed from the distance calculation over the MD trajectory that the interaction between Mg1-F and Mg4-F is stronger than that between Mg2-F, Mg3-F, and Mg5-F. Short average distances (~2 Å) between Mg1–OP1(U7), Mg1–OP2(G8), Mg3-OP2 (6A), Mg3-OP2 (7U), Mg3-OP1 (41U), Mg3-OP2 (42G), Mg4-OP1 (6A), and Mg4-OP1 (42G), indicate strong electrostatic interactions. The distance between Mg2+ (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) and F− (Figure S2a–e), as well as Mg2+ and the backbone of Fluoride riboswitch (Figures S3–S5), remains almost constant throughout the simulation time, indicating a stable interaction. The Mg2+–backbone distance analysis suggests that Mg2+, as an essential constituent of the fluoride riboswitch, forms a stable metal coordination site. On the other hand, Table S1c shows that the interaction between K+ and the backbone of Fluoride riboswitch is volatile and dynamic. There is no direct interaction between F− and backbone phosphates of the fluoride riboswitch aptamer. F− is coordinated by three Mg2+ ions (Mg1, Mg3, Mg4), which in turn are coordinated to the G5-p-A6-p-U7-p-G8 and A40-p-U41-p-G42 backbone phosphates and water molecules (Figure 1c). 3.2. Structural Variability Base pair parameters and base pair step parameters deliver a great deal of information to assess the overall geometry of the double-helical region of the fluoride riboswitch, such as pseudoknot, stem1, and stem2 (Tables S2a,b and S3a,b). Roll values are mostly observed as large positive (~10°). In most cases, twist values are around 300–400. Slide values are around −1.5 Å in A-form RNA. Rise values are around 3.4 Å in RNA. Base pair parameters and base pair step parameters suggest that most of the base pairs in the pseudoknot and stem regions of the holo and apo form of Fluoride riboswitch aptamer predominantly adopt A-form RNA structures with proper stacking between canonical base pairs. Standard deviation values are within acceptable ranges for most of the base pairs, indicating reasonable conformational stabilities. Average roll and twist angles are rather unusual suggesting deformation of some of the steps involving canonical base 5 G:C14 W:W C (pseudoknot), 28 U:A 33 W:W C (stem2) as well as non-canonical base-pairs 21 A:G 3 s:s T (loop1), 38 U:A 6W:W T (pseudoknot) in holo form. On the other hand 20 A:C 17s:s C (loop1), 28 U:A 33 W:W C (stem2), 38 U:A 6 W:W T (pseudoknot) of apo form exhibit significant conformational alteration. Slide value ranges from small positive values to as large as −3 Å for the steps containing non-canonical base-pairs. Buckle, propeller, and stagger values indicate high stability with strong, stable, and planar base pairing of most of the base-pairs in pseudoknot and stem1 of holo and apo form against deformation or rupture of H-bonds. Large open angle is indicative of disruption of the H-bond in loop1 of 20 A:Cs:s C 17, 21 A:Gs:s T 3, and ion recognition site of 41 U:Cs:h T44 for both holo and apo. Tables S2c and S3c show the backbone torsion angles: χ, pseudo-rotation phase angle (P), pseudo-torsion angles: ƞ and Ɵ. The glycosidic torsion angle χ adopts an anti-conformation (+900 to +1800; –900 to –1800), whereas sugar pucker prefers C3’-endo conformation for most of the residues within [00,360] range for the fluoride riboswitch aptamer in both systems. Our data show that A6 (pseudoknot), A19 (loop1), G24 (stem2), G42 (stem1), G52 (terminal residue) of holo and G24 (stem2), G42(stem1), G52 (terminal residue) of apo adopt syn conformation (−900 to +900). η and θ values are clustered around −1700 (−1700 + 3600 = 1900) and −1400 (−1400 + 3600 = 2200), respectively, indicating a regular helical-like conformation of pseudoknot, stem1, and stem2. Unusual average ƞ and Ɵ values are observed in the loop and terminal regions for both holo and apo systems, often with very high standard deviations. They exhibit C2’-endo pseudorotamer to accommodate the conformational strain. The pseudo-rotation phase angles for all the bases of loop1 and the terminal region show a bimodal or multimodal distribution, indicating higher structural variability. Table S4 represents the stacking overlap values between two Watson-Crick base pairs in the helical region of the pseudoknot, stem1, and stem2, which are found to be around 40–55 Å2, indicating significant stacking. A medium amount of stacking is observed between isolated bases in loop1 and loop2. However, non-canonical base pair 20 A: C 17 (s:s C) and 21 A: G 3 (s:s T) of loop1 do not stack well. 3.3. Conformational Thermodynamics We show histograms (Figure 3) for a few conformational variables in different RNA conformations. The peak of the histogram indicates the most probable value of the corresponding microscopic conformational variable. H(ƞA6) and H(ƞU7), the histograms of ƞ for bases A6 (Figure 3a) and U7 (Figure 3b) at the ion recognition site, show that the height of the single-peaked distribution in the holo form is higher than in the apo form, indicating that the flexibility of A6 and U7 is significantly reduced in holo form upon ion binding. H(θA19) of loop1 (Figure 3c) shifts from a single peak in the apo form to multiple peaks in the holo form, whereas H(θC22) (Figure 3d) transitions from a double peak in apo to a single peak in holo, reflecting loop-specific conformational rearrangements. H(ν3G36) of stem2 (Figure 3e) shows single peaks in both states, with increased peak height in the holo state, consistent with restricted mobility. H(θU41) and H(ηG42) (Figure 3f,g) are broad in apo but become sharp in holo, indicating reduced conformational fluctuations at the ion recognition site. C50 exhibits bimodal θ distributions in both holo and apo states, H(θC50), as shown in Figure 3h, revealing persistent flexibility that may support terminal mobility and overall RNA conformational adaptability. The sharper and narrower peaks observed for the holo form indicate that ligand binding markedly reduces the conformational flexibility of the fluoride riboswitch. In contrast, broader peaks reflect severe conformational fluctuations, while bimodal distributions highlight transitions between two isomeric conformations. Conversely, sharp unimodal peaks denote conformational stability within a single isomeric state with reduced randomness. Changes in free energy and conformational entropy were quantified by analyzing histograms of all microscopic degrees of freedom in the holo aptamer relative to the apo form. The relative stability and flexibility of the holo system compared to the apo form are illustrated in a color-coded cartoon representation in Figure S6. We next discuss the residue-wise (Figures S7–S12) and domain-wise (Table 2) total changes in conformational thermodynamics (kJ·mol−1) of the fluoride riboswitch aptamer. Table 2 illustrates the domain-wise overall changes in conformational thermodynamics (ΔG and TΔS), obtained by summing the base-pair contributions across all microscopic conformational variables, including inter–base-pair steps, intra–base-pair steps, sugar–phosphate backbone torsion angles, pseudotorsion angles, and sugar pucker. (a) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the Pseudoknot region of the holo system in comparison to the apo system (kJ/mol). (b) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the stem1 region of the holo system in contrast to the apo system (kJ/mol). (c) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the stem2 region of the holo system in comparison to the apo system (kJ/mol). (d) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the loop1 region of the holo system in contrast to the apo system (kJ/mol). (e) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the loop2 region of the holo system in comparison to the apo system (kJ/mol). (f) The changes in conformational thermodynamics of the Ion recognition site region of the holo system in comparison to the apo system (kJ/mol). 3.3.1. Pseudoknot We first examine the conformational thermodynamic changes in free energy (ΔG) and entropy (TΔS) arising from inter–base-pair step parameters (Figure S7a,b). Tilt, roll, shift, and rise corresponding to the pseudoknot region do not depend significantly on the base pair steps. On the other hand, twist has maximum stabilization at step G5:C14 and destabilization at A6:U38. We observe that TΔS for all the inter-base-pair step parameters except slide is not sensitive to base pair steps. The step A6:U38 shows the maximum order by slide. The total changes in conformational free energy and entropy for each base pair of inter-base pair parameters exhibit the highest stabilization and order at A40:U48. Next, we consider the intra-bp step parameters (Figure S7c,d). Open, propeller, shear, stagger, and stretch corresponding to the pseudoknot region are not sensitive to bases. The buckle value at A6:U38 exhibits maximum stabilization and order. Finally, total changes in conformational free energy and entropy are computed for each bp of intra-bp parameters. It shows that significant conformational destabilization and disorder at G2:C17, G3:C16, and A40:U48, while maximum stabilization and order at A6:U38. Torsion angle: α, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, and χ do not contribute significantly to the bases of the pseudoknot (Figure S7e,f) except at A6:U38. A6 and U38 show maximum order and stabilization corresponding to the evaluation of the total changes in conformational free energy and entropy over all degrees of freedom of the torsion angle. Next, we shed light on the changes in conformational thermodynamics in terms of pseudo torsion angles (Figure S7g,h). ΔG of η and θ at A6 corresponding to (i) holo form with respect to apo form shows maximum stabilization. ΔG and TΔS of θ at C18 contribute maximum destabilization and disorder for the holo form with respect to the apo form. ΔG of η does not contribute significantly to bases from G15 to C18. We observe that A6 and U38 get highly stabilized and ordered based on the computation of total changes in conformational free energy and entropy in terms of pseudo-torsion angle. Let us now shed light on the total changes in conformational thermodynamics due to sugar-pucker at pseudoknot (Figure S7i,j). ν0, ν1, ν2, ν3 and ν4 do not contribute significantly towards G2, G3, C16 and C17.ν0 exhibits stabilization and order at C4, G5, C14 and G15.ν1 shows the significant stabilization and order at bases G5 & C14 whereas ν2 exhibits the highest stabilization and order at A6 and U38. On the other hand, we find that ν0 and ν4 have maximum destabilization at A6 and U38, while ν3 shows maximum stabilization at base C4 and G15. We evaluate the total changes in conformational free energy and entropy over the sugar torsion angle (ν0, ν1, ν2, ν3, and ν4), which shows the significant stabilization and order at the bases G5, A6, C14, U38, A40, U48. At the same time, the most destabilization and disorder are observed at the bases G2, G3, C16, and C17. 3.3.2. Stem1 At first, we shed light on the changes in conformational thermodynamics in terms of inter-bp step parameters (Figure S8a,b). Tilt, roll, twist, and shift corresponding to stem1 shows maximum stabilization at the step C12:G43, whereas the steps G8:C47 and A9:U46 are energetically destabilized by roll, twist, and slide. Let us now consider the changes in entropy. TΔS of tilt, roll, slide, and shift are not sensitive to base steps A9:U46 and G10:C45. On the other hand, the rise exhibits the most disorder at base step 11G: C44 and C12:G43. Now we evaluate the total changes in conformational free energy and entropy for each bp due to inter-bp step parameters. C12:G43 exhibits maximum stabilization, while maximum destabilization occurs at G10:C45. Total changes in conformation entropy show significant conformational order at G8:C47, C12:G43, and C13:G42. Next, we discuss the changes in conformational thermodynamics due to intra-bp parameters (Figure S8c,d). The conformational free energy shows that the open conformation contributes the most to stabilizing the base step C12:G43, while the buckle causes the maximum destabilization at step 11G: C44. Stretch is not sensitive to base steps. ΔG and TΔS of buckle, propeller, and shear contribute the most to stabilizing A9:U46. Evaluation of the total changes in conformational free energy and entropy over the intra-bp parameters exhibits maximum order and stabilization at A9:U46. ΔG and TΔS of torsion angle do not show sensitivity towards the bases for the holo system (Figure S8e,f). Pseudo-torsion angle (η and θ) of ΔG and TΔS do not show sensitivity towards the bases for the holo system except G42 (Figure S8g,h). Next, we examined the changes in conformational free energy associated with sugar puckers (Figure S8i,j). The torsion angles ν1, ν2, and ν4 exhibit significant stabilization at C12 and G43. TΔS is not sensitive to the bases. The computation of total changes in conformational free energy and entropy indicates the highest disorder and destabilization at A9 and U46, while maximum order and stabilization are observed at C12 and G43. 3.3.3. Stem2 The ΔG values for inter–base-pair step parameters corresponding to stem 2 (Figure S9a,b) are not sensitive to variations in base-pair steps. On the other hand, twist contributes to maximum conformational disorder at the step U28:A33. Next, we consider the intra-bp parameters (Figure S9c,d). The changes in conformational free energy and entropy for the holo system with respect to the apo form do not depend significantly on the bps. The changes in conformational thermodynamics for sugar-phosphate and sugar-base torsion angles are not sensitive to the bases (Figure S9e,f). The total changes in conformational free energy and entropy indicate that G24, C37, C25, and G36 bases have significant stability and order. ΔG of η has maximum destabilization at U28 and A33. We observe that ΔG of η and θ are not sensitive to the bases from G34 to C37. ΔG and TΔS of θ show destabilization and disorder at C27, U28, and A33 with a maximum value at C27 (Figure S9g,h). Let us now discuss the changes in conformational thermodynamics associated with sugar puckers (Figure S9i,j). The variations in conformational free energy corresponding to ν0 indicate stabilization of bases C25, G36, C26, G35, C27, and G34. In contrast, ν1, ν2, ν3, and ν4 exhibit destabilization across all bases belonging to stem 2. Computation of the total changes in conformational free energy exhibits maximum stabilization at bases C25 and G36 and maximum destabilization at bases C27 and G34. We note that TΔS values associated with sugar puckers are not strongly base-dependent. The total changes in conformational entropy indicate maximum ordering at bases C25 and G36, whereas maximum disorder is observed at C27 and G34. 3.3.4. Loop1 We see that ΔG and TΔS of sugar-phosphate backbone torsion angles, along with sugar-base torsion angle at all bases corresponding to loop1, are not sensitive to bases (Figure S10a,b). The calculation of total changes in conformational free energy and entropy shows the most conformational destabilization and disorder at base A20. Total ΔG and TΔS show that the most conformational stabilization and order at the base C22.ΔG and TΔS of η show destabilization and disorder at loop1 for the holo form with respect to the apo (Figure S10c,d). Holo form with respect to apo form contributes maximum destabilization and disorder at base A21. ΔG and TΔS of η and θ contribute significantly to the stabilization and order at U23. Conformational free energy and entropy for sugar pucker angles corresponding to loop1 of ν0, ν1, ν2, ν3, and ν4 (Figure S10e,f) do not contribute significantly to the bases. The total changes in conformational thermodynamics due to sugar-puckers indicate the most conformational stabilization and order at base C22, while maximum destabilization and disorder occur at A20. 3.3.5. Loop2 Sugar-phosphate backbone torsion angles, along with sugar-base torsion angle corresponding to loop2, do not contribute significantly to bases (Figure S11a,b). Total changes in conformational free energy and entropy show destabilization and disorder at base A31. Next, we shed light on pseudo-torsion angle (Figure S11c,d). The destabilization of loop 2 is reflected in the ΔG values of η and θ for the holo form relative to the apo form. TΔS of ƞ and θ show significant destabilization and disorder at base A31 and A32. TΔS of θ exhibits the highest stabilization and order at the base A30 for the holo form with respect to the apo. We find that for sugar-puckers, base A31 has maximum destabilization and disorder (Figure S11e,f). 3.3.6. Ion Recognition Site Now we examine the conformational thermodynamics due to sugar-phosphate, sugar-base, and sugar-pucker torsion angles at all bases corresponding to the ion recognition site of Fluoride riboswitch aptamer. OP1/OP2 of P6, P7, P8, P41 and P42 of RNA participate in coordination to Mg2+ (1, 3, 4). Mg2+ (2) is coordinated with OP2 of P40, while for Mg2+ (5), the coordinating residue is O2’ of P52. K+ is coordinated with OP1 of P5, P6, P7. molecules. Water molecules fulfill the rest of the coordination in all the cases. Sugar base torsion angle, along with sugar-phosphate torsion angles, shows ordering and stabilization at all bases corresponding to the ion recognition site (Figure S12a,b). The total changes in conformational free energy and entropy show a maximum at A6 and U41. We now discuss the changes in conformational thermodynamics in terms of pseudo torsion angles (Figure S12c,d). We observe that ΔG and TΔS of η and Ɵ at A6, 7U, and A40 corresponding to holo form with respect to apo form show significant stabilization and order. In contrast, the highest stabilization ΔG and ordering (TΔS) Ɵ at U41, and for η, it is G42. Next, we shed light on the conformational thermodynamics for sugar pucker angles (Figure S12e,f). ν0, ν1 and ν4 exhibit maximum contribution to stabilize the A40 observed from ΔG value. ΔG of ν2 and ν3 contribute the most at U41. TΔS of ν0, ν1, ν2, ν3 and ν4 have maximum ordering at U41. Computation of the total changes in conformational free energy and conformational entropy over all sugar-puckers shows that G8 has the maximum destabilization and disorder, while most stabilization and order are observed at A6 and U41. Table 2a–f shows significant stabilization in pseudoknot, stem1, and ion recognition site of the holo form with respect to the apo form. The intra-base pair is the primary factor to destabilize the holo system compared to the apo form. In contrast, the inter-base pair, torsion, pseudo-torsion, and sugar angle degrees of freedom are the main factors to stabilize the holo form over the apo form in the pseudoknot region. We found that most of the changes in conformational free energy and entropy are insignificant compared to the thermal energy (≈2.5 kJ/mol) at room temperature for the intra-base pair of the pseudoknot. The intra-base pair is also the main factor in destabilizing stem2, whereas the pseudo-torsion angle and inter-base pairs are the key factors in stabilizing stem1 of the holo system. We observe that loop1 and stem2 get significantly destabilized. We find that most of the changes for loop2 in conformational free energy and entropy (contribution from torsion angle, pseudo-torsion angle, and sugar angle) are insignificant compared to the thermal energy (≈2.5 kJ/mol) at room temperature. These observations indicate that specific base pair interactions and backbone torsional degrees of freedom collectively govern the conformational thermodynamics underlying riboswitch function.

(a)

Pseudoknot

Inter Base-pair

Intra Base-pair

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

−3.39

2.13

−9.81

−6.01

−7.56

−24.64

T∆S (KJ/mol)

−9.05

0.45

−12.29

−6.59

−7.77

−35.25

(b)

Stem1

Inter Base-pair

Intra Base-pair

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

−7.57

−1.53

−0.75

−8.68

−4.26

−22.79

T∆S (KJ/mol)

−9.98

−5.73

−0.44

−10.45

−1.14

−27.74

(c)

Stem2

InterBase-pair

IntraBase-pair

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

0.92

5.46

1.80

−0.14

2.73

10.77

T∆S (KJ/mol)

4.04

7.57

1.12

−0.29

−0.39

12.05

(d)

Loop1

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

14.13

4.05

3.14

21.32

T∆S (KJ/mol)

23.74

5.51

2.47

31.72

(e)

Loop2

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

2.55

1.56

−0.14

3.97

T∆S (KJ/mol)

3.26

1.86

1.69

6.81

(f)

Ion recognition site

Torsion-angle

Pseudotorsion-angle

Sugar-angle

Total

∆G(KJ/mol)

−23.01

−20.85

−15.77

−59.63

T∆S (KJ/mol)

−30.09

−23.39

−17.67

−71.15

Recent advances in riboswitch research increasingly integrate experimental data with advanced computational modeling to elucidate ligand recognition and accelerate inhibitor discovery. Aboul-ela et al. (2015) provided a seminal framework linking aptamer–ligand interactions to expression platform dynamics, establishing the mechanistic foundation for rational riboswitch engineering [43]. Computational approaches now play a central role, with studies by Wakchaure et al. (2020, 2021, 2022) and Jana et al. (2020) employing molecular dynamics (MD) and well-tempered metadynamics to dissect ligand binding in FMN, TPP, and PreQ1 riboswitches, yielding atomistic insights to guide ligand analog design [44,45,46,47]. Elkholy et al. (2024) further demonstrated how structure-based virtual screening and multistage computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) can identify SAM-I riboswitch inhibitors, while Antunes et al. (2025) expanded this toolkit to probe guanosine-analog binding in the 2′-deoxyguanosine-II riboswitches, highlighting riboswitch plasticity and specificity. In the adenine riboswitch, ligand binding to the aptamer domain induces an open-to-closed conformational switch that remodels the expression platform and regulates gene expression. Guodong et al. (2020) demonstrated that this process is governed not only by binding affinity but also by pocket dynamics, with purine and pyrimidine analogs exhibiting distinct electrostatic contributions, and pyrimidines being accommodated by a more flexible binding pocket [48,49,50]. Ligand binding modulates transitions between open and closed states, defined by key nucleotide interactions (U51/A52 vs. C74/C75). These findings indicate that the dynamic properties of the binding pocket play a critical role in modulating riboswitch function. Consequently, rational ligand design must consider not only binding affinity but also the conformational adaptability of the pocket. Collectively, these studies underscore a progress from foundational mechanistic modeling to increasingly sophisticated computational pipelines that combine enhanced sampling molecular dynamics, quantum chemical calculations, and AI-driven CADD approaches, positioning riboswitches as promising RNA drug targets and synthetic biology tools [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. The healthcare system faces a profound challenge in managing life-threatening bacterial infections due to the accelerating emergence of antibiotic resistance. This growing threat necessitates the development of next-generation antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action to effectively counter multidrug-resistant pathogens [51]. A recent development involves an artificial cell–based sensor in which a fluoride riboswitch is encapsulated within lipid vesicles [52]. The antibacterial activities of peptides Gramicidin D and Magainin 2 are enhanced in the presence of fluoride ions [53]. This suggests that combining a conventional antibiotic with a toxic anion, such as fluoride, which exhibits antibacterial properties, could be an effective strategy. Ovarian cancer (OC) is highly lethal, with few early detection options and limited treatments. Drug repositioning represents a rapid and cost-effective therapeutic strategy. Gramicidin, an antibiotic with anticancer activity, has shown potential to suppress OC growth by inducing apoptosis. Choi et al. (2023) highlight gramicidin as a promising candidate for further therapeutic exploration in OC [54]. Magainin 2, a pore-forming antimicrobial peptide, exerts its antibacterial effect by inducing bacterial apoptosis-like death [55,56]. We examine the binding modes and interaction profiles of the peptide antibiotics Gramicidin D and Magainin 2 in their interactions with the fluoride riboswitch. We further investigate whether destabilized and disordered regions of the holo fluoride riboswitch could act as docking sites for Gramicidin D and Magainin 2, thereby identifying potential structural hotspots for therapeutic targeting. The docked complexes are represented in Figure 4a for Gramicidin D and Figure 4b for Magainin 2. 4.1. Gramicidin D Binding Gramicidin D is a linear pentadecapeptide antibiotic with alternating L and D amino acids. Residues G5, G15, C16, C17, U38 of Pseudoknot, G24, C25, C26, C27, C37 of Stem2, A 21, 22C, 23U of Loop1, 5G, 6A, 7U, 41U, 42G of Ion Recognition Site of holo Fluoride riboswitch act as receptor interface for peptide antibiotic Gramicidin D which is confirmed from conformational thermodynamics data and HDOCK result. Later, we perform a biased docking analysis with HADDOCK, considering disordered residues A21, C22, U23, G24, C25, C26, and C27 as the active residues of the Fluoride riboswitch. Residues FVA1, DVA6, Val7, Trp11, DLE12, Trp13 of chain A and Ala3, DLE4, DVA8, Trp9, DLE10, Trp13, DLE14, Trp15 of chain B of Gramicidin D, which are found to lie in the vicinity (~4.5Å), act as ligand interface for receptor Fluoride riboswitch. Interfacial residues from Gramicidin D show significant hydrophobic interaction. 4.2. Magainin2 Binding The Hebrew word “magain” means “shield”. Conformational thermodynamics data and HDOCK results ensure that the destabilized and disordered residues — C18, A19, A20, A21, C22, U23 of loop1, 24G, 25C, 26C, 27C, 28U, A33, G34, G35, G36, C37 of stem2 of the holo Fluoride riboswitch — act as a receptor interface. A biased docking analysis with HADDOCK has been performed with Fluoride riboswitch and Magainin 2, considering these destabilized and disordered residues of loop1 and stem2 as the active residues of Fluoride riboswitch. Residues Lys4, Phe5, Ser8, Lys11, Phe12, Lys14, Ala15, Phe16, Gly18, Glu19, Ile20, Met21, Asn22, Ser23 of Magainin 2, which are found to lie in the vicinity (~4.5Å), act as ligand interface for receptor Fluoride riboswitch. Interfacial residues Ala, Gly, Ile, Met, and Phe from Magainin 2 show significant hydrophobic interaction, whereas Lys and Ser undergo dominant electrostatic interaction with the Fluoride riboswitch. Docking score from HDOCK (Table S5a) as well as HADDOCK (Table S5b) demonstrates that the Docked complex of Gramidin D has a stronger binding affinity for Fluoride riboswitch than that of Magainin 2. The HADDOCK result illustrates that Van der Waals energy and electrostatic energy favor the formation of the peptide-RNA complex. In contrast, desolvation energy has less impact on it. Figure S13 presents the zoomed view of the interface of the energy-minimized docked complexes. We further dock the peptide drugs Gramicidin D and Magainin 2 to the average simulated structure of the apo Fluoride riboswitch. We show the energy values upon minimization (Figure S14a,b) for the docked complexes. The minimum energy for the apo Fluoride Riboswitch-Gramicidin D complex and the apo Fluoride riboswitch-Magainin 2 complex is considerably higher than the holo Fluoride Riboswitch-Gramicidin D complex and the holo Fluoride riboswitch-Magainin 2 complex. Thus, we find that peptide drug binding to the holo Fluoride riboswitch is more favorable compared to the apo Fluoride riboswitch. The Fluoride riboswitch achieves ligand recognition through a tightly packed RNA fold and a network of Mg2+ ions rather than extensive (F−) ligand–RNA hydrogen bonding, reducing opportunities for small-molecule mimicry. Its natural ligand, the simple inorganic anion F−, possesses extremely high solvation energy and minimal chemical complexity, rendering competitive ligand design inherently challenging (Ren et al., 2012). The high electrostatic potential of the cognate ligand binding site and the dominant role of metal-mediated interactions pose barriers for conventional small-molecule screening pipelines. On the other hand, Peptides offer a larger interaction surface, enabling more extensive and specific contacts with RNA and increasing their potential for high-affinity binding. These factors emphasize the importance of pursuing unconventional approaches, such as RNA-binding macrocycles or allosteric modulators, over conventional small-molecule drugs. Chimeric antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) represent a promising strategy to address antimicrobial resistance (AMR) by targeting essential bacterial riboswitches, including glmS, FMN, TPP, and SAM-I. Conjugated with cell-penetrating peptides such as pVEC, these ASOs efficiently enter bacterial cells and bind to riboswitch mRNA, inducing RNase H-mediated degradation [57]. This selective mechanism suppresses bacterial growth while sparing human cells, offering a safe and adaptable platform for antibiotic development. Riboswitch-targeted antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) offer considerable promise against multidrug-resistant pathogens by facilitating the design of both narrow- and broad-spectrum therapeutic agents. Advances in macrocyclic peptide discovery (Pal et al., 2022) indicate that riboswitch–peptide interactions are biochemically feasible. However, they remain primarily synthetic or hypothetical and have not been observed in nature. Owing to their constrained structures, macrocyclic peptides have emerged as promising modulators of protein–protein interactions and could potentially be engineered to target RNA elements such as riboswitches. However, their application to riboswitches remains nascent, with most studies focusing on synthetic constructs rather than naturally occurring systems [58,59]. Backbone torsions and sugar puckers dictate conformational flexibility and folding in RNA molecular dynamics simulations. The observed variations in torsions are highly dependent on the force field employed, because force fields define the torsional potential energy surfaces and the relative stability of different conformers. Different RNA force fields—such as AMBER ff99bsc0χOL3 and CHARMM36 can produce markedly different populations of backbone and sugar puckers, affecting base-stacking, loop flexibility, and tertiary interactions. Consequently, discrepancies in torsional sampling often reflect force field parameterization more than intrinsic RNA dynamics, emphasizing the need for careful force field selection and validation against experimental data such as NMR or crystallography [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Molecular dynamics simulations of the fluoride riboswitch were performed using the AMBER ff99bsc0 χOL3 force field, which is widely employed for RNA to capture backbone conformations and topology accurately. This approach allowed us to model the dynamic behavior of the riboswitch and examine ligand interactions at the atomistic level. However, it is essential to note that standard additive force fields like ff99bsc0 χOL3 have inherent limitations, particularly in describing RNA–ion interactions. Fixed-charge models neglect polarization and charge transfer effects, which can impact the coordination and dynamics of divalent cations such as Mg2+, critical for fluoride binding and stabilization of the riboswitch tertiary structure. Additionally, slow ion-binding events and correlated ion–ion interactions are complex to capture with conventional MD timescales, potentially limiting the accuracy of predicted ion positions and binding energetics. Accurate modeling of RNA is further hindered by slow ion-binding dynamics, potential errors in crystallographic ion placement, and the oversimplified treatment of bulk ion effects. Despite these constraints, the simulations provide valuable mechanistic insights into the fluoride riboswitch’s conformational landscape and serve as a foundation for rational ligand design, guiding both experimental validation and future computational refinements. By emphasizing thermodynamic principles, our approach provides a rigorous framework for identifying functional residues, especially in systems where NMR or crystallographic data are unavailable, thereby extending its applicability to a broader range of biomolecular studies [68,69,70,71,72]. These results underscore how geometry and thermodynamics jointly govern function and ligand recognition of the riboswitch. Computational predictions of riboswitch–ligand interactions require experimental validation to confirm biological relevance. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) can precisely quantify ligand binding affinities and thermodynamic parameters, providing a direct complement to docking simulations. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) and fluorescence titration assays enable medium-throughput screening of multiple ligand candidates, facilitating efficient prioritization for detailed studies. Ligand-induced RNA conformational dynamics can be mapped using in-line probing and single-molecule FRET (smFRET), capturing structural transitions under physiological conditions. For atomic-level validation, high-resolution X-ray crystallography and solution NMR spectroscopy can confirm predicted binding poses. Finally, transcription termination assays and cell-based reporter systems will assess functional efficacy by demonstrating riboswitch-mediated regulation in vitro and in vivo. Collectively, these complementary methods establish a rigorous pipeline for validating computer-aided drug design (CADD) strategies targeting riboswitches [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84].

In summary, our findings elucidate the molecular basis of ligand recognition in the fluoride riboswitch, enhancing our understanding of nucleic acid structure and function. Conformational thermodynamic analysis of the holo form with respect to apo forms revealed that structural elements such as the pseudoknot, Stem1, and ion coordination sites confer energetic and entropic stability, whereas Loop1, Loop2, Stem2, and unpaired nucleotides exhibit significant disorder and destabilization. Critical interactions, including the pseudoknot-like reversed Watson–Crick A6•U38 and reversed Hoogsteen A40•U48 base pairs, underpin the riboswitch’s higher-order architecture. Importantly, thermodynamically destabilized residues in Loop1 and Stem2 represent promising sites for non-cognate ligand engagement. These findings extend our fundamental understanding of RNA–ligand interactions and establish a rational foundation for designing nucleic acid–based ligands and aptamers, thereby facilitating the development of targeted therapeutics that harness riboswitch-mediated regulation.

AMP

Adenosine Monophosphate

ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate (implied in riboswitch context, though not explicitly written)

BPFIND

Base Pair FINDer (software)

CEST-NMR

Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer—Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

CHIMERA

UCSF Chimera Molecular Modeling Software

DFT

Density Functional Theory

FMN

Flavin Mononucleotide

GROMACS

GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations (MD package)

HADDOCK

High Ambiguity Driven protein–protein Docking

HBM

Histogram-Based Method

HDOCK

Hybrid protein–protein Docking webserver

ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

LBD

Ligand Binding Domain

LINCS

Linear Constraint Solver (MD algorithm)

MD

Molecular Dynamics

mRNA

Messenger RNA

NAD+

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (oxidized form)

NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

PME

Particle Mesh Ewald

PYMOL

Python Molecular Graphics System

SAM

S-adenosyl Methionine

smFRET

Single-molecule Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer

tRNA

Transfer RNA

VMD

Visual Molecular Dynamics

Abbreviations of non-canonical base pairs

W: WT involves Watson–Crick edges of both bases in a trans orientation, commonly referred to as a reverse Watson–Crick base pair.

H: WT involves the Hoogsteen edge of the first base pairing with the Watson–Crick edge of the second base in a trans orientation.

s: sC involves Sugar edges of both bases pair in a cis orientation, forming a weak, non-polar C–H…N hydrogen bond.

s: sT involves Sugar edges of both bases pair in a trans orientation, also forming a weak, non-polar C–H…N hydrogen bond.

s: hT involves Sugar edge of the first base pairs with the Hoogsteen edge of the second base in trans orientation, forming a weak, non-polar C–H…N hydrogen bond.

Abbreviations of structural elements of Fluoride riboswitch

PK

Pseudoknot

P1

Stem1

P2

Stem2

L1

Loop1

L2

Loop2

The author confirms that she was solely responsible for the conception, design, analysis, interpretation, drafting, visualization and final approval of the article.

Data supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, through a Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded to Soumi Das. Computational resources were provided by the Technical Research Center at S. N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Kolkata.

Download Supplementary Materials Figures S1-S14 and Tables S1-S5 here.

[1] Das, S. Decoding the Mechanistic Landscape of Protein-DeoxyriboNucleic Acid Recognition: A Comprehensive Review. ES Chem. Sustain. 2025, 4, 1610. [CrossRef]

[2] Genz, L.R.; Nair, S.; Sweeney, A.; Topf, M. Drug targeting of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 95, 103165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3] RNA as a drug target; Book Series: Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry, 2024. [CrossRef]

[4] Huang, L.; Lilley, D.M.J. Some General Principles of Riboswitch Structure and Interactions with Small-Molecule Ligands. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2025, 58, e13. [CrossRef]

[5] Kavita, K.; Breaker, R.R. Discovering Riboswitches: The Past and the Future. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 48, 119–141. [CrossRef]

[6] Ellinger, E.; Chauvier, A.; Romero, R.A.; Liu, Y.; Ray, S.; Walter, N.G. Riboswitches as Therapeutic Targets: Promise of a New Era of Antibiotics. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 433–445. [CrossRef]

[7] Bu, F.; Lin, X.; Liao, W.; Lu, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, Y.; Peng, X.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Ribocentre-Switch: A Database of Riboswitches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D265–D272. [CrossRef]

[8] Mohsen, M.G.; Breaker, R.R. Prospects for Riboswitches in Drug Development. Methods Princ. Med. Chem. 2024, 203–226. [CrossRef]

[9] Giarimoglou, N.; Kouvela, A.; Maniatis, A.; Papakyriakou, A.; Zhang, J.; Stamatopoulou, V.; Stathopoulos, C. A Riboswitch-Driven Era of New Antibacterials. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1243. [CrossRef]

[10] Hansen, L.N.; Kletzien, O.A.; Urquijo, M.; Schwanz, L.T.; Batey, R.T. Context-Dependence of T-Loop Mediated Long-Range RNA Tertiary Interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168070. [CrossRef]

[11] Ren, A.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Patel, D.J. Fluoride Ion Encapsulation by Mg2+ Ions and Phosphates in a Fluoride Riboswitch. Nature 2012, 486, 85–89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12] Kumar, S.; Reddy, G. Mechanism of Fluoride Ion Encapsulation by Magnesium Ions in a Bacterial Riboswitch. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 9267–9281. [CrossRef]

[13] Chawla, M.; Credendino, R.; Poater, A.; Oliva, R.; Cavallo, L. Structural Stability, Acidity, and Halide Selectivity of the Fluoride Riboswitch Recognition Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 137, 299–306. [CrossRef]

[14] Hu, G.; Yu, X.; Li, Z. Unveiling Putative Excited State and Transmission of Binding Information in the Fluoride Riboswitch. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024. [CrossRef]

[15] Thavarajah, W.; Silverman, A.D.; Verosloff, M.S.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Jewett, M.C.; Lucks, J.B. Point-of-Use Detection of Environmental Fluoride via a Cell-Free Riboswitch-Based Biosensor. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 9, 10–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16] Ariyarathna, M.R.; Nissanka, J.P.; Methlal, K.; Abeyrathne, K.D.; Satharasinghe, M.; Banushan, P.; Manawadu, D.; Arachchilage, G.M.; Silva, G.N. Simple and Cost-Effective Fluoride Riboswitch-Based Whole-Cell Biosensor for the Determination of Fluoride in Drinking Water. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 5552–5562. [CrossRef]

[17] Wedekind, J.E.; Dutta, D.; Belashov, I.A.; Jenkins, J.L. Metalloriboswitches: RNA-Based Inorganic Ion Sensors That Regulate Genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9441–9450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[18] Wu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W. Multidimensional Applications and Challenges of Riboswitches in Biosensing and Biotherapy. Small 2023, 20, e2304852. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19] Zhao, B.; Guffy, S.L.; Williams, B.; Zhang, Q. An Excited State Underlies Gene Regulation of a Transcriptional Riboswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 968–974. [CrossRef]

[20] Lee, J.; Sung, S.E.; Lee, J.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, B.S. Base-Pair Opening Dynamics Study of Fluoride Riboswitch in the Bacillus cereus CrcB Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3234. [CrossRef]

[21] Das, A.; Chakrabarti, J.; Ghosh, M. Conformational Contribution to Thermodynamics of Binding in Protein-Peptide Complexes through Microscopic Simulation. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 1274–1284. [CrossRef]

[22] Das, A.; Chakrabarti, J.; Ghosh, M. Conformational Thermodynamics of Metal-Ion Binding to a Protein. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 581, 91–95. [CrossRef]

[23] Sikdar, S.; Chakrabarti, J.; Ghosh, M. A Microscopic Insight from Conformational Thermodynamics to Functional Ligand Binding in Proteins. Mol. BioSyst. 2014, 10, 3280–3289. [CrossRef]

[24] Maganti, L.; Ghosh, M.; Chakrabarti, J. Molecular Dynamics Studies on Conformational Thermodynamics of Orai1–Calmodulin Complex. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 36, 3411–3419. [CrossRef]

[25] Mondal, M.; Chakrabarti, J.; Ghosh, M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Interaction Between Bacterial Proteins: Implication on Pathogenic Activities. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2017, 86, 370–378. [CrossRef]

[26] Dutta, S.; Ghosh, M.; Chakrabarti, J. In-Silico Studies on Conformational Stability of Flagellin–Receptor Complexes. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 38, 2240–2252. [CrossRef]

[27] Mandal, S.C.; Maganti, L.; Mondal, M.; Chakrabarti, J. Microscopic Insight to Specificity of Metal Ion Cofactor in DNA Cleavage by Restriction Endonuclease EcoRV. Biopolymers 2020, 111, e23396. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28] Kole, K.; Gupta, A.M.; Chakrabarti, J. Conformational Stability and Order of Hoogsteen Base Pair Induced by Protein Binding. Biophys. Chem. 2023, 301, 107079. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[29] Das, S. Decoding the effect of temperatures on conformational stability and order of ligand unbound thermosensing adenine riboswitch using molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2025, 1–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[30] Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [CrossRef]

[31] Zgarbová, M.; Otyepka, M.; Šponer, J.; Mládek, A.; Banáš, P.; Cheatham, T.E.; Jurečka, P. Refinement of the Cornell et al. Nucleic Acids Force Field Based on Reference Quantum Chemical Calculations of Glycosidic Torsion Profiles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 2886–2902. [CrossRef]

[32] Petrova, S.S.; Solov’ev, A.D. The Origin of the Method of Steepest Descent. Hist. Math. 1997, 24, 361–375. [CrossRef]

[33] Lemak, A.S.; Balabaev, N.K. On the Berendsen Thermostat. Mol. Simul. 1994, 13, 177–187. [CrossRef]

[34] Saito, H.; Nagao, H.; Nishikawa, K.; Kinugawa, K. Molecular Collective Dynamics in Solid Para-Hydrogen and Ortho-Deuterium: The Parrinello–Rahman-Type Path Integral Centroid Molecular Dynamics Approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 953–963. [CrossRef]

[35] Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [CrossRef]

[36] Schrödinger, L.; De Lano, W. PyMOL. 2020. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/pymol (accessed on 6 July 2022).

[37] Bansal, M.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Ravi, B. NUPARM and NUCGEN: Software for Analysis and Generation of Sequence Dependent Nucleic Acid Structures. Bioinformatics 1995, 11, 281–287. [CrossRef]

[38] Das, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Mitra, A.; Bhattacharyya, D. Non-Canonical Base Pairs and Higher Order Structures in Nucleic Acids: Crystal Structure Database Analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2006, 24, 149–161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[39] Das, A.; Chakrabarti, J.; Ghosh, M. Thermodynamics of interfacial changes in a protein–protein complex. Mol. BioSyst. 2013, 10(3), 437–445. [CrossRef]

[40] Moulick, A.G.; Chakrabarti, J. Fluctuation-dominated ligand binding in molten globule protein. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63(17), 5583–5591. [CrossRef]

[41] Yan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Huang, S.Y. HDOCK: A Web Server for Protein–Protein and Protein–DNA/RNA Docking Based on a Hybrid Strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W365–W373. [CrossRef]

[42] Van Zundert, G.C.P.; Rodrigues, J.P.G.L.M.; Trellet, M.; Schmitz, C.; Kastritis, P.L.; Karaca, E.; Melquiond, A.S.J.; Van Dijk, M.; De Vries, S.J.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. The HADDOCK2.2 Web Server: User-Friendly Integrative Modeling of Biomolecular Complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 428, 720–725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[43] Aboul-ela, F.; Huang, W.; Elrahman, M.A.; Boyapati, V.; Li, P. Linking Aptamer--Ligand Binding and Expression Platform Folding in Riboswitches: Prospects for Mechanistic Modeling and Design. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2015, 6, 631–650. [CrossRef]

[44] Wakchaure, P.D.; Jana, K.; Ganguly, B. Structural Insights into the Interactions of Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) and Riboflavin with FMN Riboswitch: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 3856–3866. [CrossRef]

[45] Jana, K.; Wakchaure, P.D.; Ghosh, S.; Bandyopadhyay, T.; Ganguly, B. Quantum Chemical and Well-Tempered Metadynamics Study to Design Adenine Analogs for Orthogonal Preq1 Riboswitch. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 4635–4643. [CrossRef]

[46] Wakchaure, P.D.; Ganguly, B. Molecular Level Insights into the Inhibition of Gene Expression by Thiamine Pyrophosphate (TPP) Analogs for TPP Riboswitch: A Well-Tempered Metadynamics Simulations Study. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2021, 104, 107849. [CrossRef]

[47] Wakchaure, P.D.; Ganguly, B. Deciphering the Mechanism of Action of 5FDQD and the Design of New Neutral Analogues for the FMN Riboswitch: A Well-Tempered Metadynamics Simulation Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 24, 817–828. [CrossRef]

[48] Elkholy, N.; Hassan, R.; Bedda, L.; Elrefaiy, M.A.; Arafa, R.K. Exploration of SAM-I Riboswitch Inhibitors: In-Silico Discovery of Ligands to a New Target Employing Multistage CADD Approaches. Artif. Intell. Chem. 2024, 2, 100044. [CrossRef]

[49] Antunes, D.; Santos, L.H.S.; Caffarena, E.R.; Guimarães, A.C.R. Structural and Dynamic Properties of Guanosine-Analog Binding to 2′-Deoxyguanosine-II Riboswitch: A Computational Study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2025, 1–22. [CrossRef]

[50] Hu, G.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Wang, J. Ligand Binding Mechanism and Its Relationship with Conformational Changes in Adenine Riboswitch. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1926. [CrossRef]

[51] Monserrat-Martinez, A.; Gambin, Y.; Sierecki, E. Thinking Outside the Bug: Molecular Targets and Strategies to Overcome Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[52] Boyd, M.A.; Thavarajah, W.; Lucks, J.B.; Kamat, N.P. Robust and Tunable Performance of a Cell-Free Biosensor Encapsulated in Lipid Vesicles. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd6605. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[53] Nelson, J.W.; Zhou, Z.; Breaker, R.R. Gramicidin D Enhances the Antibacterial Activity of Fluoride. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2969–2971. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[54] Choi, M.S.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.J.; Heo, K. Gramicidin, a Bactericidal Antibiotic, is an Antiproliferative Agent for Ovarian Cancer Cells. Medicina 2023, 59, 2059. [CrossRef]

[55] Kim, M.; Kang, N.; Ko, S.; Park, J.; Park, E.; Shin, D.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; et al. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity and Mode of Action of Magainin 2 against Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3041. [CrossRef]

[56] Lee, W.; Lee, D.G. Magainin 2 Induces Bacterial Cell Death Showing Apoptotic Properties. Curr. Microbiol. 2014, 69, 794–801. [CrossRef]

[57] Pavlova, N.; Traykovska, M.; Penchovsky, R. Targeting FMN, TPP, SAM-I, and glmS Riboswitches with Chimeric Antisense Oligonucleotides for Completely Rational Antibacterial Drug Development. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1607. [CrossRef]

[58] Walker, M.J.; Varani, G. Design of RNA-Targeting Macrocyclic Peptides. Methods Enzymol. 2019, 339–372. [CrossRef]

[59] Pal, S.; Hart, P. ‘T. RNA-Binding Macrocyclic Peptides. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[60] Mlýnský, V.; Kührová, P.; Pykal, M.; Krepl, M.; Stadlbauer, P.; Otyepka, M.; Banáš, P.; Šponer, J. Can We Ever Develop an Ideal RNA Force Field? Lessons Learned from Simulations of the UUCG RNA Tetraloop and Other Systems. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025. [CrossRef]

[61] Šponer, J.; Krepl, M.; Banáš, P.; Kührová, P.; Zgarbová, M.; Jurečka, P.; Havrila, M.; Otyepka, M. How to Understand Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations of RNA and Protein–RNA Complexes? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 8, e1405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[62] Šponer, J.; Bussi, G.; Krepl, M.; Banáš, P.; Bottaro, S.; Cunha, R.A.; Gil-Ley, A.; Pinamonti, G.; Poblete, S.; Jurečka, P.; et al. RNA Structural Dynamics as Captured by Molecular Simulations: A Comprehensive Overview. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4177–4338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[63] Gray, J.G.; Case, D.A. Refinement of RNA Structures Using Amber Force Fields. Crystals 2021, 11, 771. [CrossRef]

[64] Cesari, A.; Bottaro, S.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Banáš, P.; Šponer, J.; Bussi, G. Fitting Corrections to an RNA Force Field Using Experimental Data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 3425–3431. [CrossRef]

[65] Kührová, P.; Mlýnský, V.; Zgarbová, M.; Krepl, M.; Bussi, G.; Best, R.B.; Otyepka, M.; Šponer, J.; Banáš, P. Correction to “Improving the Performance of the Amber RNA Force Field by Tuning the Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions”. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 16, 818–819. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[66] He, W.; Naleem, N.; Kleiman, D.; Kirmizialtin, S. Refining the RNA Force Field with Small-Angle X-ray Scattering of Helix–Junction–Helix RNA. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 3400–3408. [CrossRef]

[67] Tan, D.; Piana, S.; Dirks, R.M.; Shaw, D.E. RNA Force Field with Accuracy Comparable to State-of-the-Art Protein Force Fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1346–E1355. [CrossRef]

[68] Vangaveti, S.; Ranganathan, S.V.; Chen, A.A. Advances in RNA Molecular Dynamics: A Simulator’s Guide to RNA Force Fields. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 8, e1396. [CrossRef]

[69] Panteva, M.T.; Giambaşu, G.M.; York, D.M. Force Field for Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ Ions That Have Balanced Interactions with Nucleic Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 15460–15470. [CrossRef]

[70] Allnér, O.; Nilsson, L.; Villa, A. Magnesium Ion–Water Coordination and Exchange in Biomolecular Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 1493–1502. [CrossRef]

[71] Grotz, K.K.; Cruz-León, S.; Schwierz, N. Optimized Magnesium Force Field Parameters for Biomolecular Simulations with Accurate Solvation, Ion-Binding, and Water-Exchange Properties. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 2530–2540. [CrossRef]