APA Style

Kalyani Pawar, Dhanush Devappa B C, Soumit Banerjee, Appala Venkata Ramana Murthy. (2025). Integrating Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) Encryption and Forward Error Correction (FEC) Codes for Secure and Robust Underwater Optical Wireless Communication. Communications & Networks Connect, 2 (Article ID: 0008). https://doi.org/10.69709/CNC.2025.100920MLA Style

Kalyani Pawar, Dhanush Devappa B C, Soumit Banerjee, Appala Venkata Ramana Murthy. "Integrating Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) Encryption and Forward Error Correction (FEC) Codes for Secure and Robust Underwater Optical Wireless Communication". Communications & Networks Connect, vol. 2, 2025, Article ID: 0008, https://doi.org/10.69709/CNC.2025.100920.Chicago Style

Kalyani Pawar, Dhanush Devappa B C, Soumit Banerjee, Appala Venkata Ramana Murthy. 2025. "Integrating Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) Encryption and Forward Error Correction (FEC) Codes for Secure and Robust Underwater Optical Wireless Communication." Communications & Networks Connect 2 (2025): 0008. https://doi.org/10.69709/CNC.2025.100920.

ACCESS

Research Article

ACCESS

Research Article

Volume 2, Article ID: 2025.0008

Kalyani Pawar

kalyani_jap23@diat.ac.in

Dhanush Devappa B C

dhanush.pap24@diat.ac.in

Soumit Banerjee

soumitbanerjee06@gmail.com

Appala Venkata Ramana Murthy

avrmurthy@diat.ac.in

Department of Applied Physics, Defence Institute of Advanced Technology, Pune-411025, India

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 04 Mar 2025 Accepted: 28 Jul 2025 Available Online: 29 Jul 2025 Published: 01 Sep 2025

Underwater Optical Wireless Communication (UOWC) offers a potential alternative to traditional Radio Frequency (RF) and acoustic methods, which suffer from low speed, short range, and high latency in underwater conditions. Reliability and security in UOWC are affected by signal degradation caused by turbidity, scattering, and absorption, which remain significant challenges. This study investigates a UOWC system by combining different modulation formats and Forward Error Correction (FEC) codes with Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) encryption and testing on a 4m in-house underwater channel. While FEC codes help reduce bit errors caused by the underwater channel, RSA encryption adds an additional layer of security by protecting the data from eavesdropping. The information is first encrypted and then processed through modulation and Forward Error Correction, if needed. The experimental results for the output file sizes of different modulation schemes and FEC codes aligned with theoretical expectations. For instance, the file size with repeat code (3) was three times the original; with repeat code (5), it was five times larger. OOK-RZ produced files twice as large as OOK-NRZ, while PPM resulted in a file size 16 times the original, and so on. Among the various FEC codes and modulation schemes employed, the results show that using Hamming, Bose–Chaudhuri–Hocquenghem (BCH), and Reed–Solomon codes improve system stability and security by nearly 1.5 times compared to using no FEC, particularly when integrated with PPM and DPIM modulation schemes. This approach offers a promising solution for applications in underwater robotics, environmental monitoring, and defence, demonstrating the potential of UOWC as a secure communication system for challenging and dynamic underwater conditions.

Underwater operations, from scientific exploration to naval defence, increasingly demand high-speed, low-latency communication systems. Conventional acoustic and radio frequency systems struggle in aquatic environments. Acoustic signals, despite their range, suffer from low bandwidth and susceptibility to noise, while RF signals attenuate rapidly in seawater [1,2,3,4]. Underwater Optical Wireless Communication (UOWC) offers a promising alternative, using blue-green light to achieve high data rates over short to moderate distances. The optical source at the transmitter end modulates the light as per the input data and transmits through the underwater medium. The received signal is demodulated to retrieve the original information from the light signal. The complete UOWC system can be used for several potential applications in underwater surveillance, underwater sensor networks, submarine-to-submarine/Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) [5,6,7]. UOWC, however, faces significant hurdles in the ocean’s complex environment. Signal attenuation, scattering by suspended particulates, and variations in salinity and turbidity degrade performance, leading to high bit error rates (BER) and unreliable links, especially in turbulent conditions like turbid harbours [8,9,10]. One of the major challenges in UOWC is overcoming unpredictable channel impairments such as scattering, absorption, and turbulence [11,12,13]. A viable approach involves implementing various modulation and encoding schemes that enhance resistance to turbulence and ensure optimal link performance. Continuous efforts have been made to improve the modulation schemes, including On-Off Keying Non-Return to Zero (OOK-NRZ), Return-to-Zero (RZ), Pulse Position Modulation (PPM), and Differential Pulse Interval Modulation (DPIM), and other modulation schemes which balance complexity, noise resilience, and bandwidth efficiency [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Kaushal et al. [1], Jain et al. [17], and Hamilton et al. [16] have demonstrated how modulation choices critically influence system performance under varying seawater conditions. In addition to modulation schemes, which improve energy and bandwidth efficiency, encoding techniques (also known as error correction codes) ensure link reliability. Out of the two kinds of error correction codes (forward and backward), the Forward Error Correction (FEC) codes have the advantage of instantaneous implementation along with the modulation scheme. There are several types of FEC codes, among which a few codes, such as Repeat, Hamming, Bose–Chaudhuri–Hocquenghem, and Reed-Solomon (RS) codes, are feasible to implement and allow receivers to correct transmission errors without retransmission [22,23]. Tzimpragos et al. [22] and Xu et al. [23] demonstrate that advanced FEC codes maintain stable BER in turbulent waters. Adnan et al. [24] and Joudha et al. [25] further confirm FEC’s effectiveness in highly turbid environments. Repeat codes are simple but less robust; while Hamming and BCH codes offer stronger correction with moderate complexity. RS codes, though computationally intensive, excel at handling burst errors in fluctuating conditions [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Recent studies have also explored convolutional coding as a robust alternative for underwater systems. Operating on streaming data, convolutional codes are ideal for low-latency, real-time applications. Yousuf et al. [29] found that convolutional codes outperform block-based codes in high-turbidity visible light communication, maintaining lower BER in dynamic conditions. Similarly, Fathurrahman et al. [30] highlighted the efficiency of soft-decision Viterbi decoding, which adapts to rapid channel variations and enhances signal integrity. These results suggest that convolutional coding can complement traditional FEC in UWOC. While FEC addresses reliability, data security remains underexplored in many UWOC deployments. Sensitive applications, such as naval communications, require protection against unauthorized access. RSA encryption, a public-key algorithm based on prime factorization, ensures data confidentiality despite added processing demands [30,31,32,33]. In the digital era, data security is critical across both civilian and national domains. Thus, there is a need for encryption techniques in communication systems to maintain privacy between the sender and the receiver. There are mainly two types of encryption techniques, Symmetric and Asymmetric [34]. In symmetric encryption, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption. In contrast, asymmetric encryption uses two different keys—one for encryption and another for decryption. RSA is an Asymmetric encryption technique as it uses a public key to encrypt the data and a private key to decrypt it. The keys are created using two distinct prime numbers [35,36]. Integrating RSA with FEC enhances both security and resilience. Chaudhary et al. [9], Xu et al. [37], and Mohamed et al. [38] underscore the importance of cryptographic integrity in underwater sensor networks. Afifah [39] proposed a layered approach in which FEC mitigates environmental interference, while RSA secures the data. Concurrently, Dong et al. [40] and Zhang et al. [41] developed high-speed UWOC systems using multi-channel laser diodes and turbidity-tolerant wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM), achieving data rates exceeding 10 Gbit/s with minimal crosstalk. Jiang et al. [42] introduced deep learning-based signal detection to improve physical-layer performance, while Chen et al. [43] advanced simplified detection for coherent UWOC systems, signaling a trend toward hardware and algorithmic innovation. This paper presents a comprehensive end-to-end system demonstrating underwater optical wireless communication for real-time data transfer. The in-house developed system has several features to select the modulation scheme and data transfer rate of our choice, which enables the user to execute smoothly. It also includes advanced features such as integrated encoding and encryption schemes, which are essential for ensuring data reliability and security. The customized graphical user interface allows users to freely choose settings that guarantee data transfer with minimal error rates, even under adverse conditions. The system was tested and validated using a 4-meter-long in-house underwater testbed. This paper also highlights the experimental details of building such a testbed and integrating the software and hardware. We further present experimental results and analyze link performance using metrics such as execution time, encryption strength, data rate, data size, and error fraction across different encoding schemes and modulation formats. Figure 1 shows a model diagram of UOWC.

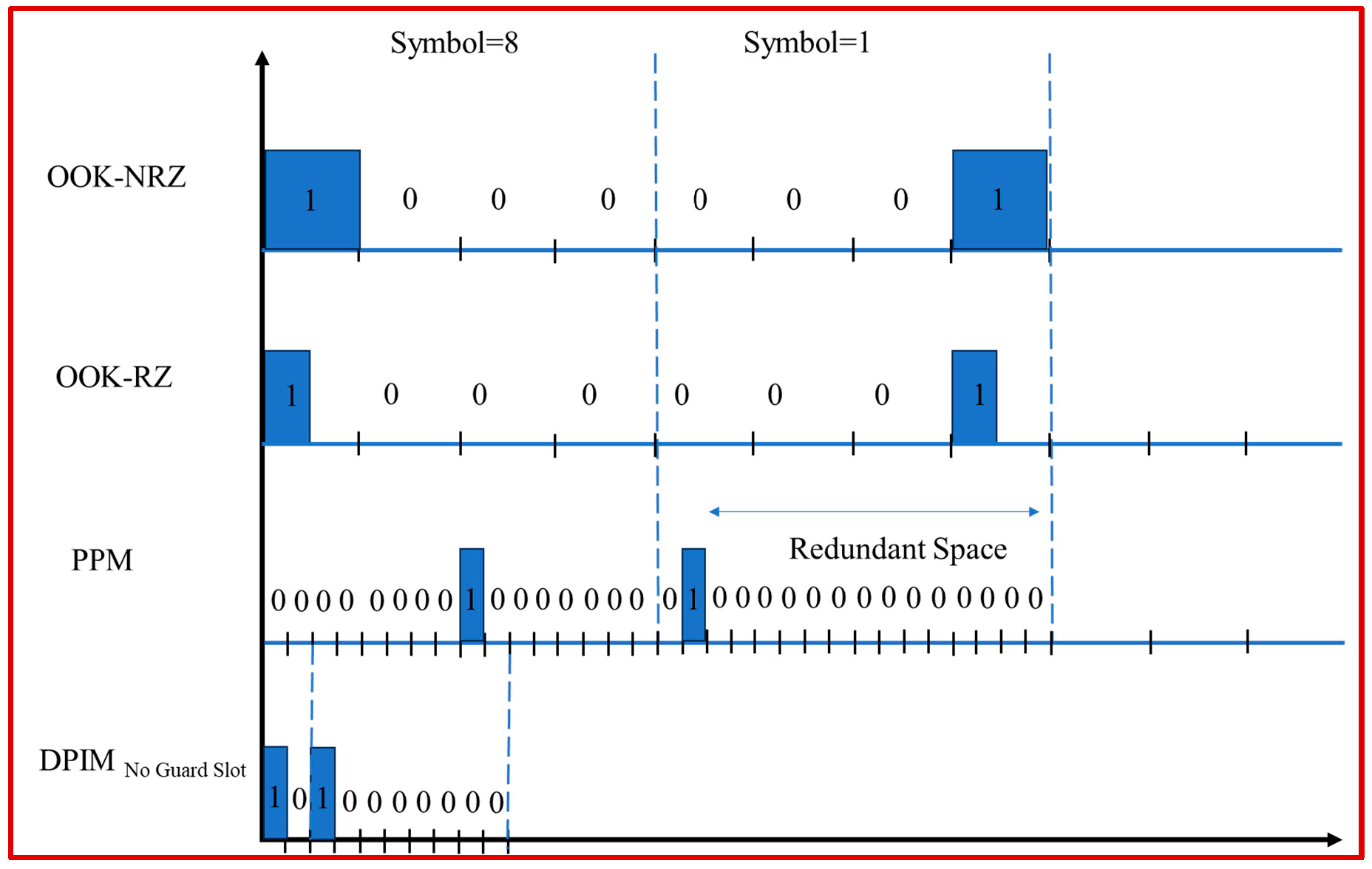

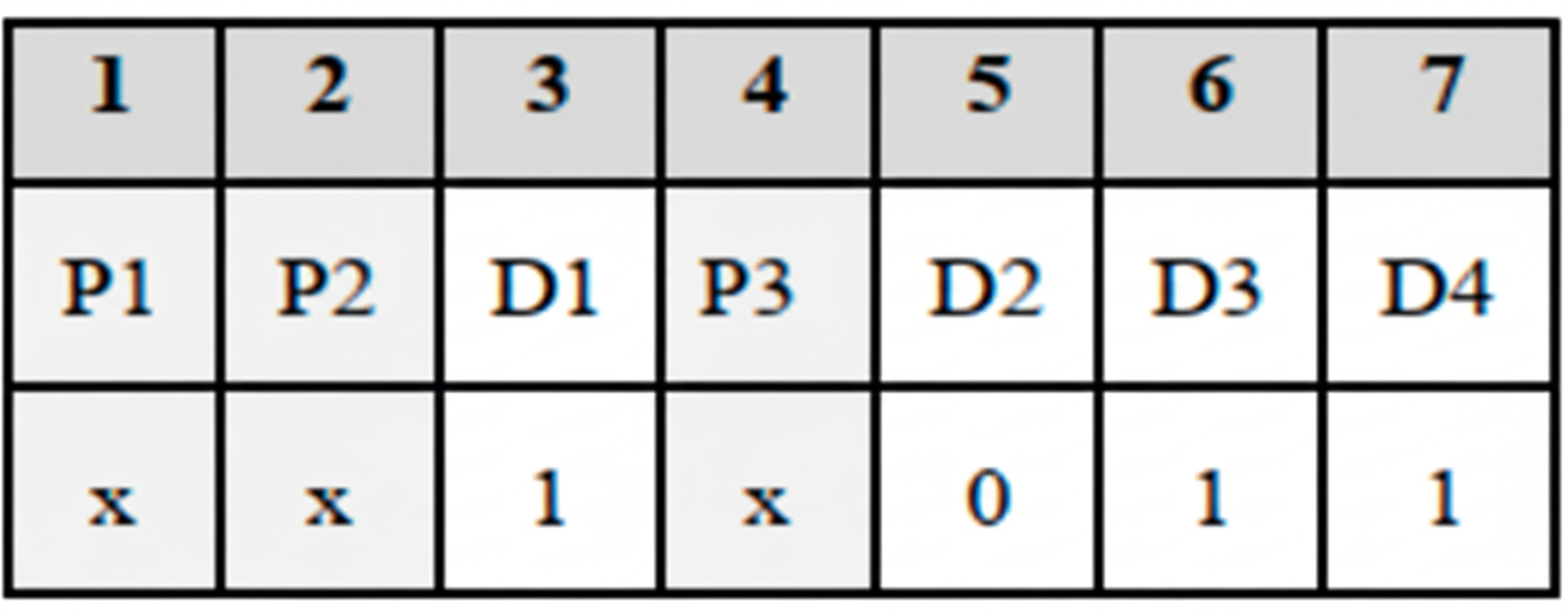

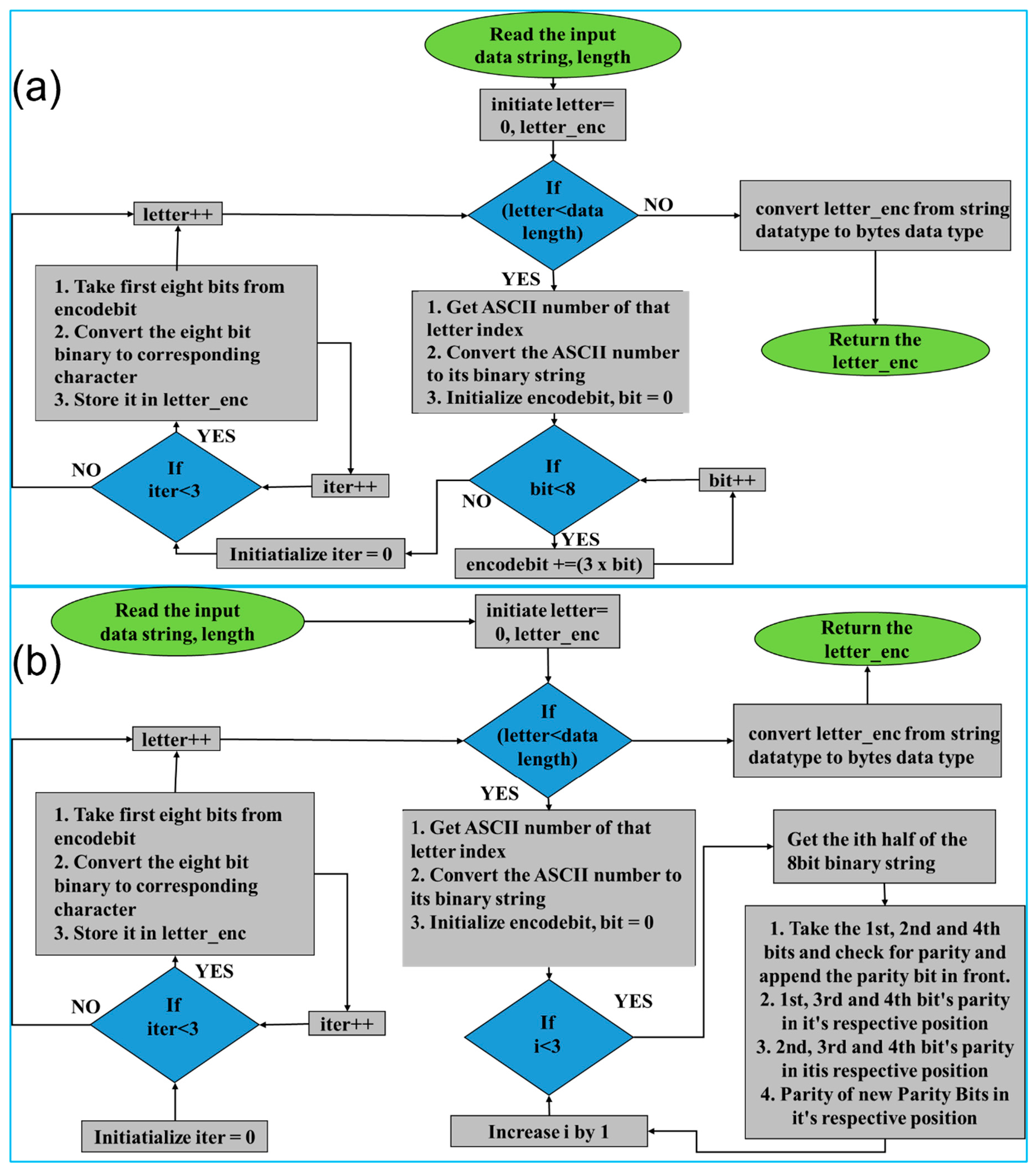

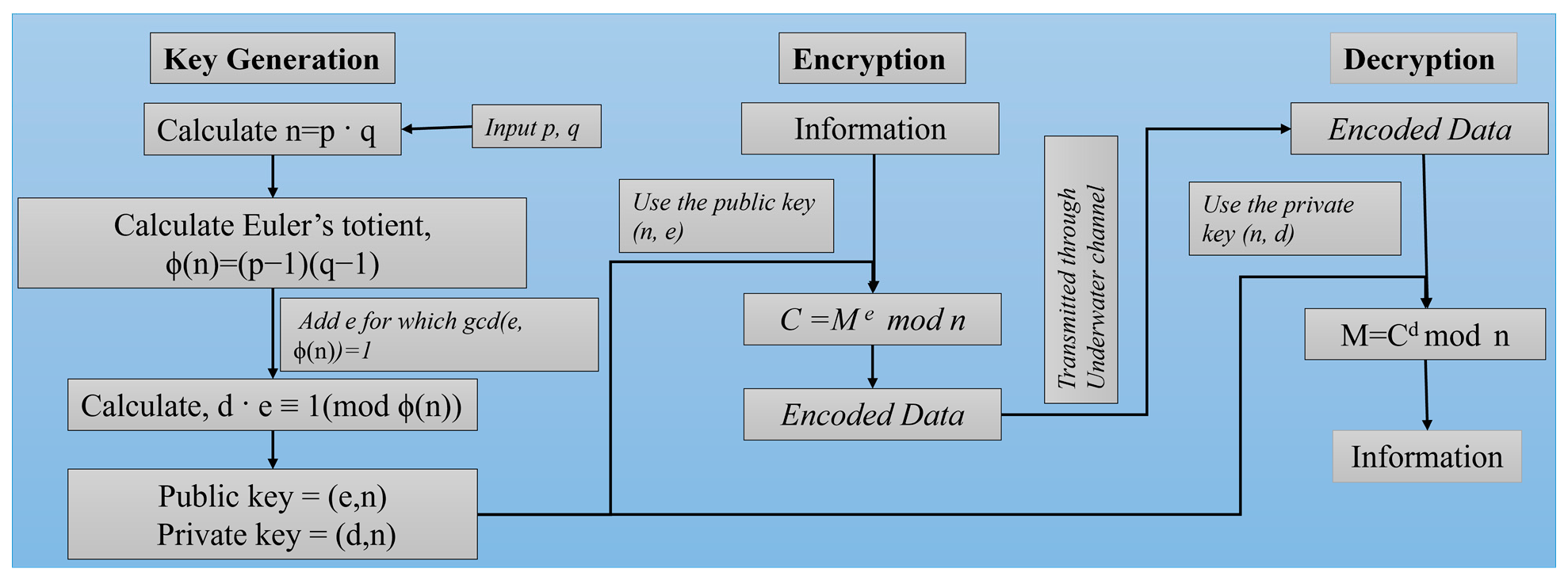

In underwater optical wireless communication, modulation schemes and error correction codes are essential to ensure effective, reliable data transmission. Modulation schemes such as OOK-NRZ, OOK-RZ, PPM, and DPIM each offer distinct benefits depending on the communication needs and environmental conditions. Forward Error Correction (FEC) codes add redundancy at the transmitter to correct errors introduced during transmission. 2.1. Various Modulation Formats Modulation techniques like OOK with Non-Return-to-Zero, Return-to-Zero formats, Pulse Position Modulation, and Differential Pulse Interval Modulation were employed in this work. These modulation techniques offer energy efficiency, bandwidth efficiency, and transmission reliability with ease of implementation. The data train of symbols 8 and 1 for all four modulation schemes mentioned is shown in Figure 2. On-Off Keying: OOK is the most basic modulation technique where the laser is ‘on’ when the bit is ‘1’ and the laser is off when the bit is ‘0’. OOK can be implemented using two main types of pulse formats: Non-Return-to-Zero (NRZ) and Return-to-Zero (RZ) [44]. In NRZ, the pulse duration is the complete bit period (Tb), whereas in RZ, the pulse duration is half of the bit period. i.e., Slot duration, i.e., Slot duration, Differential Pulse Interval Modulation: DPIM is both power efficient and bandwidth efficient as the redundant space is not present, i.e., the clock restarts every time a pulse is received, and the empty slots following it are removed. In PIM, the information is present in the number of empty slots between two pulses. A guard band can also be added right after the pulse to efficiently identify the slots; this is called Differential Pulse Interval Modulation 1 Guard Slot (DPIM 1GS), and if there is no guard band present, then it is called Differential Pulse Interval Modulation No Guard Slot (DPIM NGS) [46]. Since the symbol duration in DPIM is variable, the slot duration is chosen such that the mean symbol duration is equal to the time taken to send the same number of bits using a fixed frame length, like OOK and PPM [47]. i.e., Slot duration, 2.2. Forward Error Correction (FEC) Codes Comparing these formats along with the encoding techniques will provide a comparative feasibility and link performance analysis of a UOWC system [48,49,50]. We have employed several forward error correction codes for which a brief explanation is presented below [51]. Repeat Codes: Repeat codes, such as Repeat (3) and Repeat (5), ensure data integrity in communication systems by transmitting each bit multiple times. For example, it is three times in Repeat (3), five times in Repeat (5), and n times in Repeat (n), the higher the repetitions more secure the data will be. These simple error-correction methods are effective in low-data-rate applications and work across all formats. In Repeat (5), the bits ‘1101’ will be encoded as ‘11111111110000011111’. If the receiver receives a different bit sequence instead, i.e., one or two bits are flipped, leading to ‘11111101110010011111’, the decoder will take the most likely bit, i.e., the bit which is repeated a greater number of times in the 5-bit duration, leading to the decoded data as ‘1101’ which was the originally transmitted data sequence. A similar logic is applied in repeat (3) and other repeat codes. The Hamming Code: This ensures the correction of single-bit errors by adding parity bits to the data block. Their efficiency makes them ideal for scenarios with moderate noise interference. Each block of four data bits in Hamming code is converted into a block of seven bits by adding three parity bits to the block (see Algorithm 1). The purpose of these parity bits is to detect and correct transmission errors. Parity bits are added at 2k (k=0, 1, 2, 3…n) and are obtained by performing XOR operations on the data bits present in the remaining positions; the same is done in the receiver to decode and obtain the original data. BCH Code: BCH code is based on Galois field theory. BCH codes correct multiple random errors, making them well-suited for high bit-error-rate environments. The number of bits that a code can correct depends on the size of the Galois Field used to perform arithmetic operations within the code. Choosing a generator polynomial—a polynomial that produces a set of code words that satisfy specific error-correction properties—is a step in the development of BCH codes. The generator polynomial is built by choosing a basic Galois field component and calculating its powers. The generator polynomial is then created by combining these powers. The data is encoded using the generator polynomial, which is derived through polynomial division. The encoded data consists of the original data and the residual bits from the division, which are a set of parity bits. The number of parity bits depends on the generating polynomial’s degree. Data corruption may result from transmission errors. The receiver can detect errors in the received data by calculating the syndrome. The syndrome is computed by multiplying the supplied data by the generating polynomial. If the remainder is 0, the data is error-free. If the remainder is not zero, the syndrome identifies the location of the data errors. To fix the errors, the receiver uses the error position and syndrome to solve a sequence of linear equations. These equations can be solved using matrix algebra, and the solution provides the correct values for the missing bits. Reed-Solomon Code: RS codes encode data in multi-bit symbols, effectively handling burst errors in fluctuating water conditions. While computationally intensive, they are crucial for maintaining high data integrity in deep-sea applications. Before transmission, redundant symbols are added to the original message; these redundant symbols are calculated utilizing finite field-based mathematical techniques. The number of redundant symbols used depends on the desired level of error correction and the design of the code. By selecting a finite field and defining a generator polynomial, a Reed-Solomon code is constructed. With ‘n’ representing the number of redundant symbols, the generator polynomial has the degree ‘n’. The generator polynomial is used to generate a set of code words that satisfy particular error-correction requirements. Throughout the encoding process, the message is separated into blocks of ‘k’ symbols, where ‘k’ is the total number of information symbols. The encoder uses the generating polynomial to calculate ‘n’ redundant symbols, which are then appended to the original message to create a code word of length ‘n+k’. Once the issues have been resolved, the receiver can remove the extra symbols to restore the original message. A flowchart illustrating the encoding algorithms is provided below in Figure 3 and also included in the supplementary information (Figures S1–S8). Table 1 shows a comparative summary of the above FEC codes as below. Comparison of the execution time, error correction effectiveness, and link performance of various Forward Error Correction codes used. 2.3. Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) Encryption In addition to its speed, affordability, and limitless bandwidth, optical wireless communication offers excellent data security because of its Line of Sight (LOS) property. However, using an encryption technique will further solidify the protection. RSA is an asymmetric encryption technique; RSA uses a pair of keys: a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. The encryption strength of RSA lies in the difficulty of factoring large prime numbers, making unauthorized decryption nearly impossible without the private key. This provides a robust security measure for UOWC systems, particularly useful for high-stakes applications such as military or scientific data transfer, where protection from interception is paramount. RSA’s computational demands are a trade-off for its high level of security, making it an optimal choice in applications where secure communication outweighs the need for rapid data processing. The working of the RSA algorithm is represented in Figure 4. The proof for RSA can be obtained by using Fermat’s Little Theorem [36,52], to prove we have to show that the decryption function is the inverse of the encryption function. Fermat’s Little Theorem states, Let us apply the decryption function to the encryption function, The equation, Let us consider two equations, Then, According to Fermat’s Little Theorem: Now, Or, Using similar logic as shown above, it is possible to prove Equation (13) as well. If for two distinct prime numbers p and q, i.e., Then we can conjecture that So, from Equations (12) and (13), which have been proved, we can obtain That is the required equation to prove RSA encryption. Together, these modulation schemes, Error Correction codes, and encryption methods form a comprehensive framework to enhance the effectiveness, reliability, and security of underwater optical communication systems.

Algorithm 1. Hamming code parity bit placement

The parity bits are calculated as follows:

P1: Bit positions 3, 5, 7 -> P1 = 0

P2: Bit positions 3, 6, 7 -> P2 = 1

P3: Bit positions 5, 6, 7 -> P3 = 0

Error Correction Code

Execution Time

Error Correction Effectiveness

Link Performance

No FEC

Minimal

No Error Correction

Dependent on environmental conditions

Reed-Solomon (FEC)

High (Due to complexity)

Excellent (Handles burst errors)

Stable under fluctuating conditions

BCH (FEC)

Moderate (Higher than Hamming)

Very Good (Handles random errors)

Good in challenging environments

Hamming (FEC)

Low (Efficient)

Good (Single-bit errors)

Effective in moderate noise

Repeat Code (3 & 5)

Very Low (Simplest)

Basic (Low resilience)

Effective for low-data-rate applications

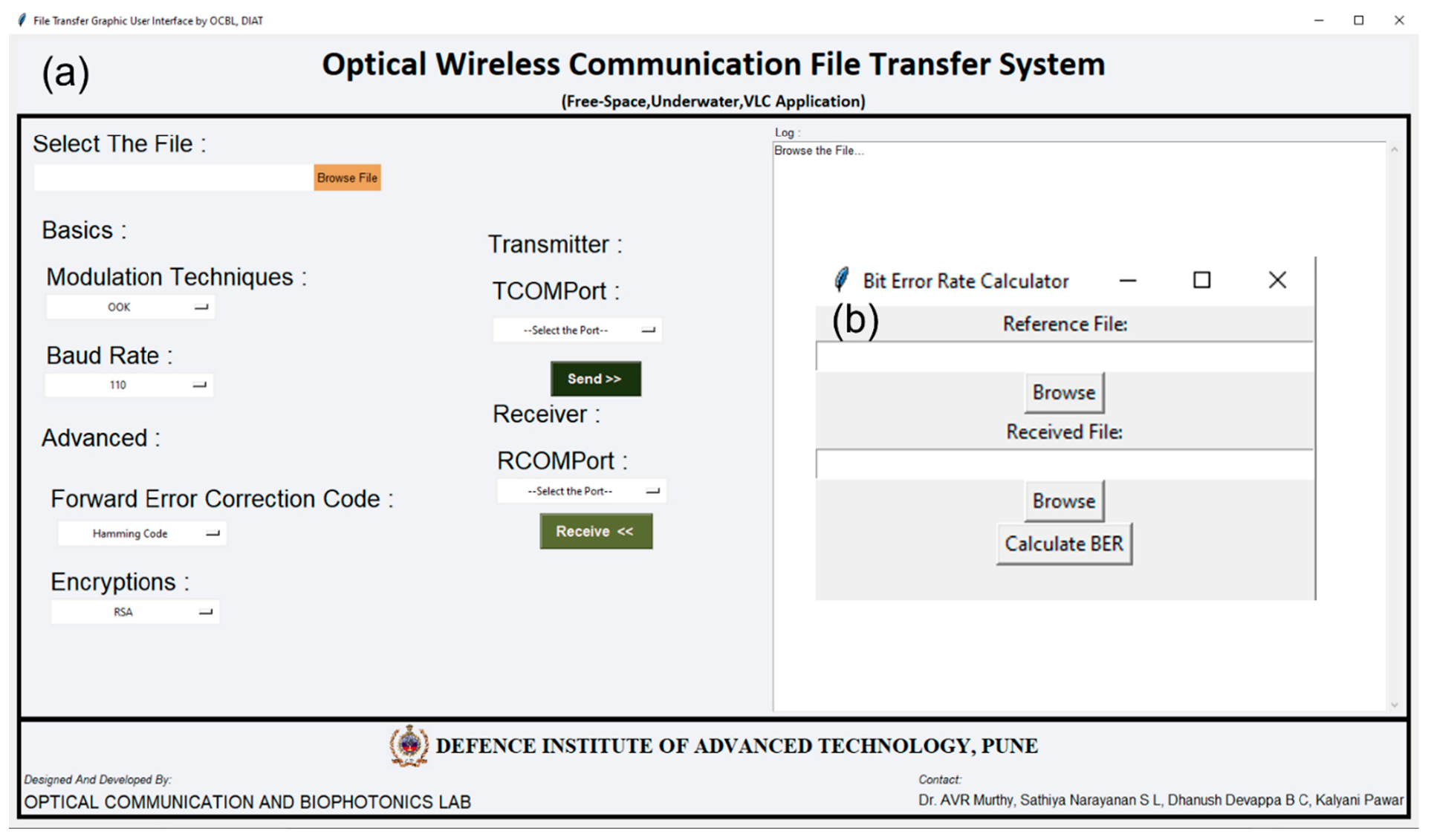

To perform UOWC experiments, a test bed has been developed in-house at a length of 4 m, which is used to simulate underwater communication conditions in a controlled environment. We have conducted numerous experiments over this 4m setup using several in-house developed modulation schemes, forward error correction codes, and RSA encryption for different data rates. This system includes a laser source of 532nm wavelength as an optical transmitter and a photodetector at the receiver end placed across the channel. Both the transmitter and the receiver are connected with the appropriate electronics and to the PC for the implementation of a real-time data transfer. We have used an in-house developed Python-based Graphical User Interface (GUI) that allows the selection of various data formats such as text, video, or image files, and enables the implementation of chosen modulation schemes, forward error correction codes, and RSA encryption. Various modulation schemes, including OOK-NRZ, OOK-RZ, PPM, and DPIM, are implemented, and the system’s performance is evaluated in this environment. Figure 5 shows the schematic and the pictures of the working experimental setup. Figure 5a describes the complete schematic of the working of the UOWC system, whereas Figure 5b–e shows the experimental pictures. Various Forward Error Correction codes, including Repeat Code 03, Repeat Code 05, Hamming, BCH, and Reed Solomon Code, were applied, and the performance was estimated. We have also estimated the practical error fraction of receiving files, which helps define link performance. We have developed a separate Graphical User Interface to calculate the error fraction using Python code. RSA encryption is also used to secure the data during transmission, protecting it from potential breaches. We have studied how the nature of the transmitting signal changes after applying all these parameters to the system. This setup enables a detailed analysis of how RSA and FEC improve secure and reliable underwater communication. The software part consists of two GUIs, as shown in Figure 6, one is used for communication, and the other deals with the calculation of BER by comparing the bits between the sent file and the received file. The GUI used for transmission is capable of handling all formats of files, as the files are brought down to binary format (0 and 1) using ‘latin1’ encoding. The GUI can function as both a transmitter and a receiver, i.e., a transceiver, and is capable of communicating at different baud rates (data rates). It incorporates various advanced techniques such as modulation methods, forward error correction codes, and encryption algorithms, all of which enhance the quality and reliability of the communication link. To make the communication between the transmitter and the receiver less complex, the GUI has an inclusion of metadata that carries all the information like file name, file size, baud rate, and techniques used for transmission. This metadata is sent one second before the file transfer begins. The receiver uses this metadata to automatically calibrate itself for file reception, thereby reducing the need for manual configuration on the receiver side. The file received is saved in the folder whose path can be specified in the GUI code. Table S1 consisting of all the standard Baud Rates used has been provided in the supplementary information. The hardware component of the experiment includes an in-house 4m water channel, lasers, photodetectors, a laser driver circuit, USB to TTL converters, and two laptops. The 4m tank is filled with tap water, and the attenuation coefficient, also known as the beam extinction coefficient, c Using the extinction coefficient, we can obtain the received optical power By using the above equations, appropriate components can be selected for the desired experimentation. The parameters for all the hardware components used for the experimentation are provided in Table 2. Parameters of the hardware setup used in the experimentation.

System Parameters used in the Experiment setup

Details

Source: DPSS Laser

MGL-FN-532-2W

Transmission Wavelength (λ)

532nm Laser diode

Transmitted power

2W

Receiver: Photodetector

TIFSS0054 laser receive module

Operating voltage

5V DC

Operating Conditions

−30 °C to 85 °C

ADC: USB to TTL converter

Waveshare 6Mbps

Operating voltage

3V and 5V DC

Channel

Underwater testbed

Communication range

4m

Baud Rate

9.6kbps-1Mbps

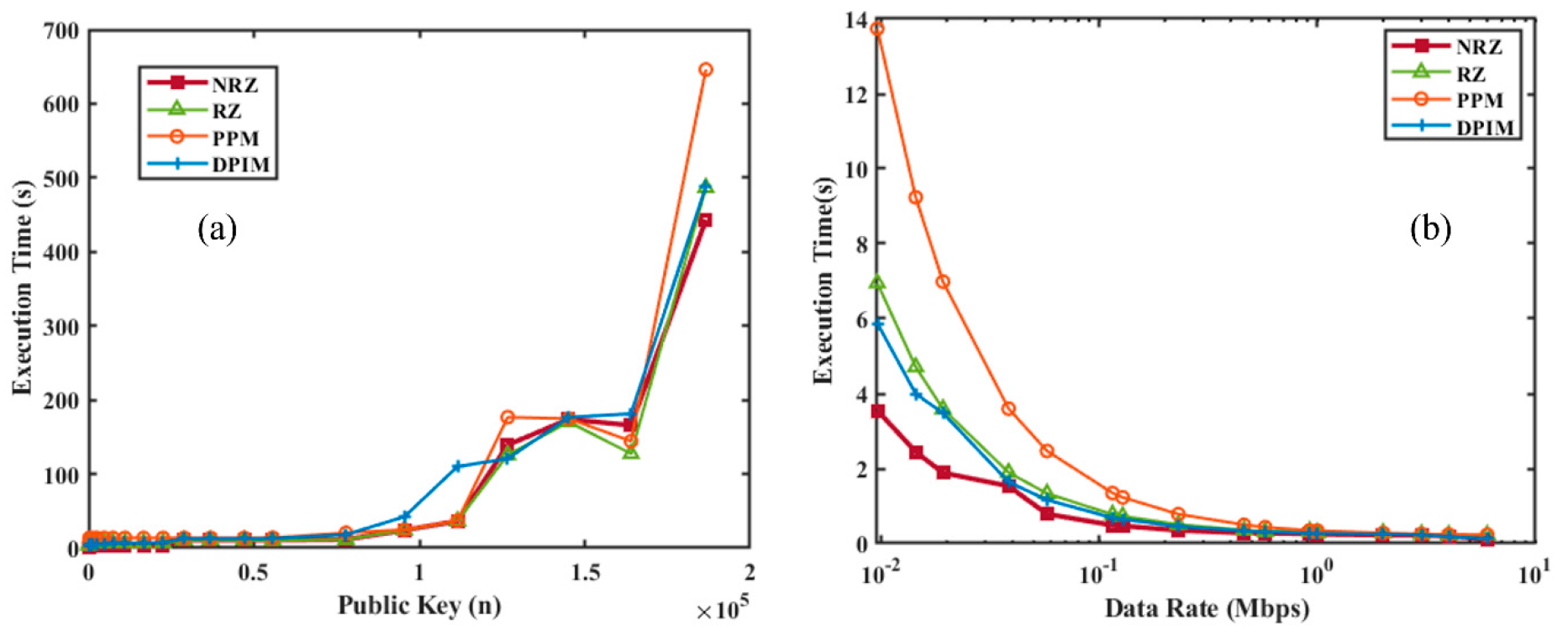

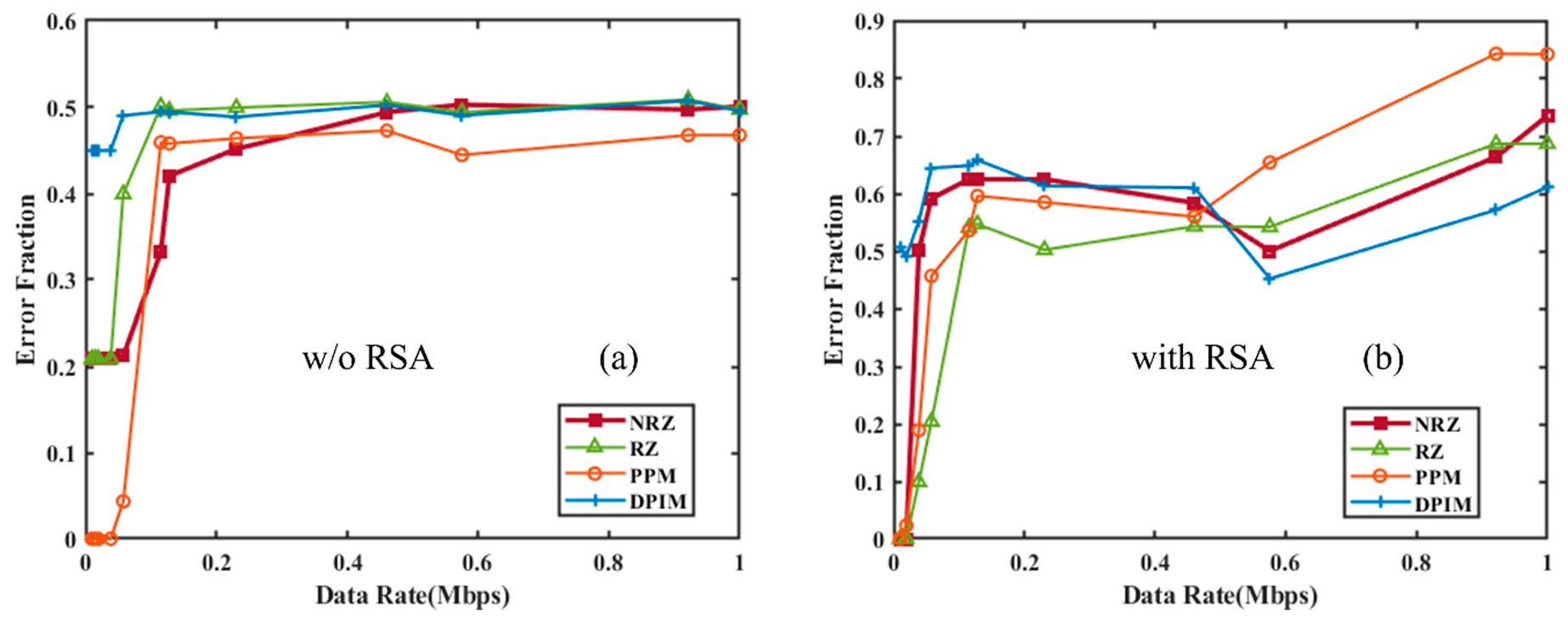

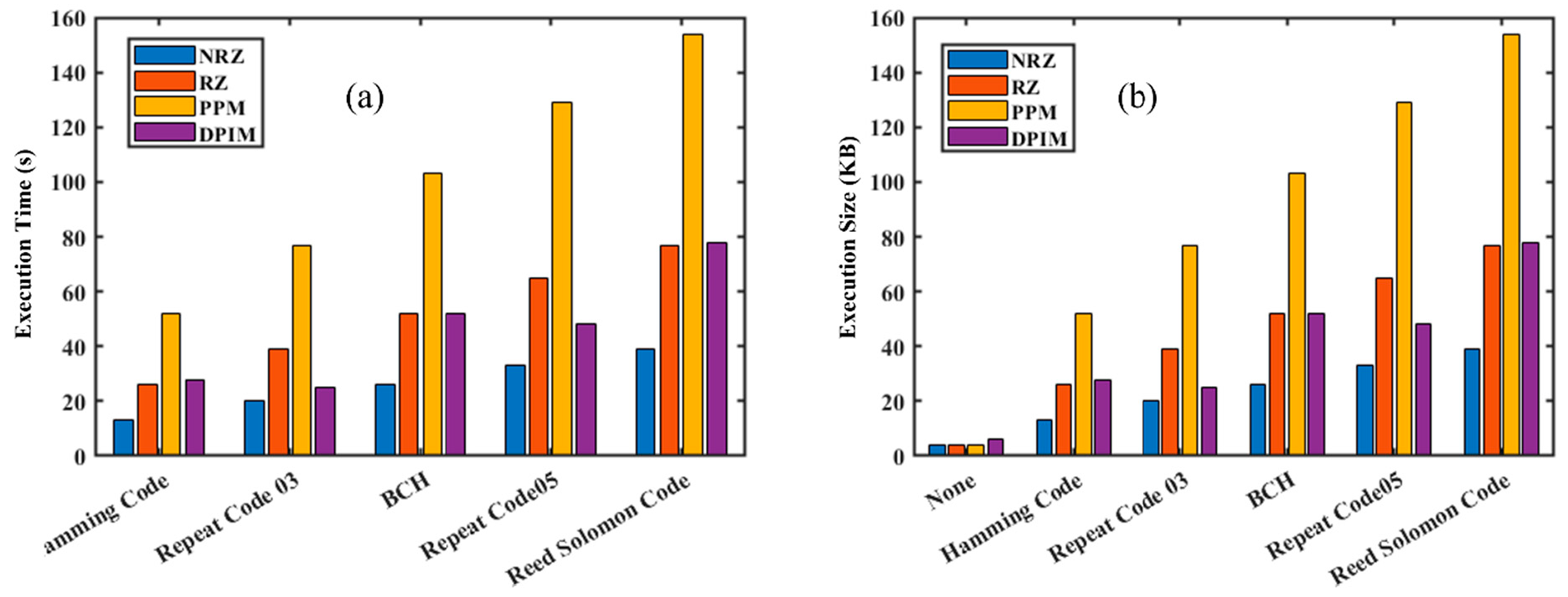

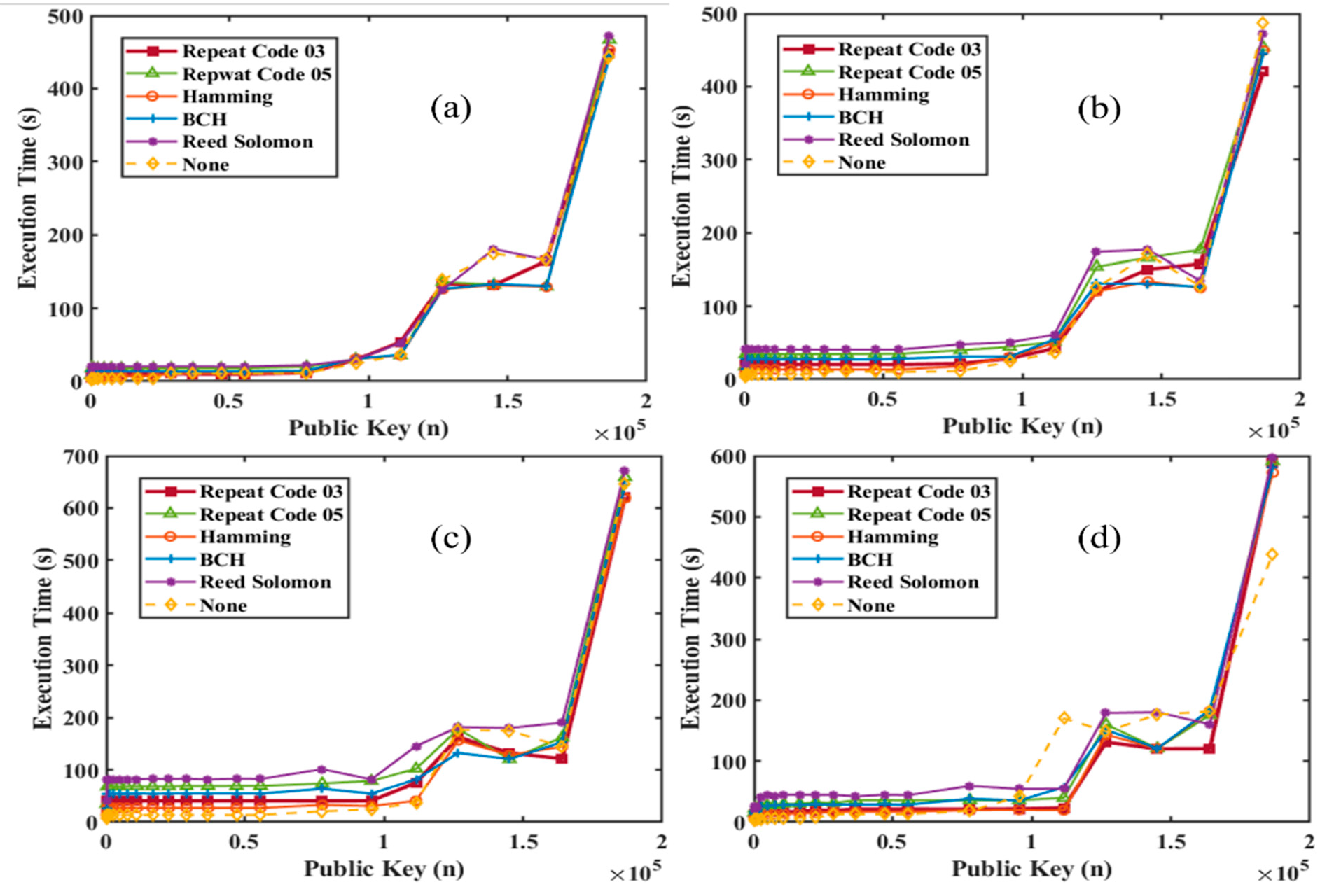

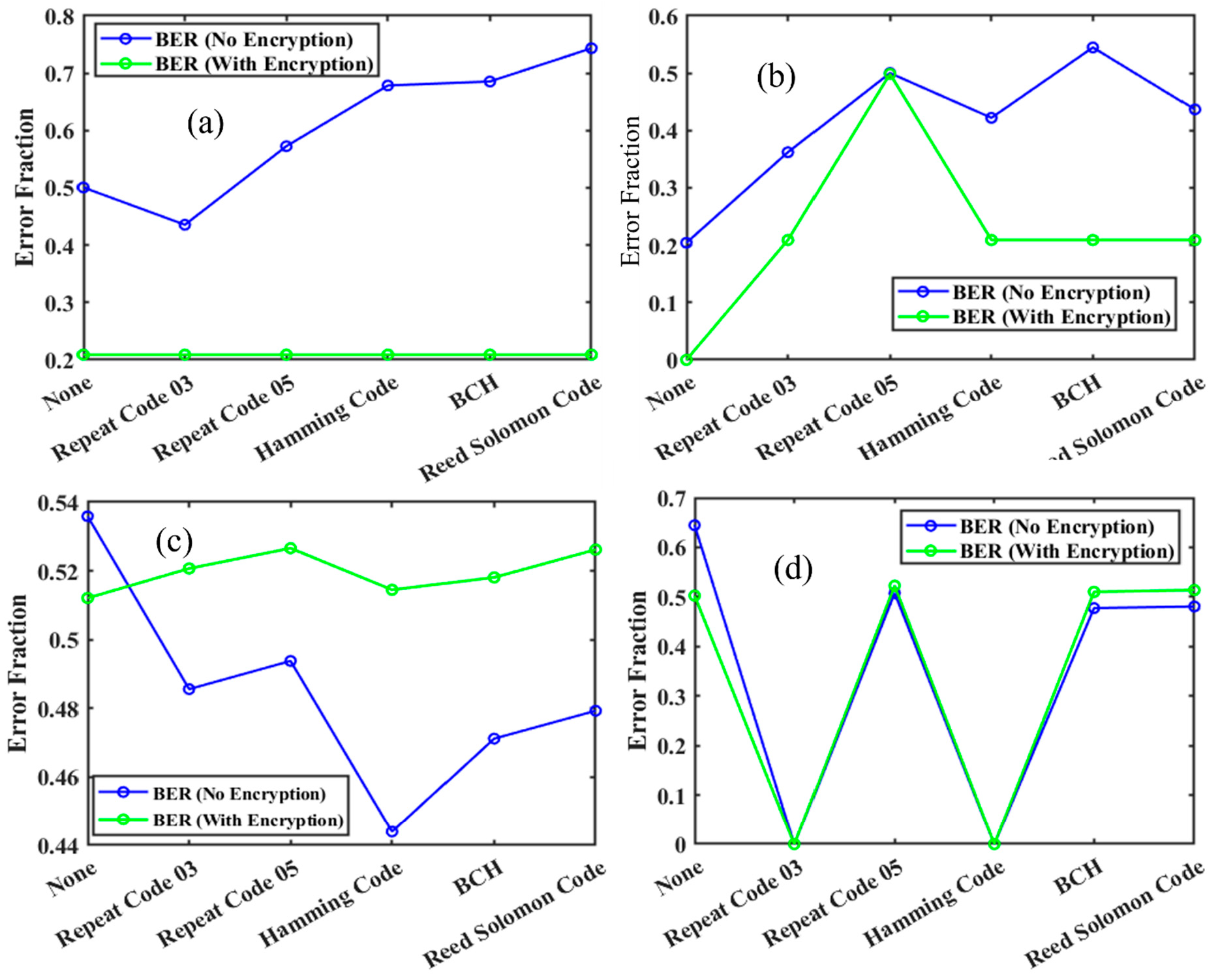

4.1. RSA Encryption Analysis As explained in Section 2, a public key and a private key are generated using combinations of prime numbers, and the data is transmitted in encrypted form. The received data will be decrypted only with the combination of these two keys. Figure 7 shows a graph illustrating the increasing strength of encryption, represented by the public and private keys, as the values of the prime numbers p and q increase. It can be noticed that there is an increasing trend in both; however, the combination of keys is unpredictable, making the decryption difficult, particularly at higher values of p, q. Table S1 listing the prime numbers used along with their corresponding public and private keys has been included in the supplementary information. 4.2. RSA Encryption and Performance Analysis of UWOC with Different Modulation Schemes We have developed RSA encryption and applied it across various modulation schemes, i.e., OOK-NRZ, RZ, PPM, and DPIM. To verify the impact of RSA encryption on different modulation schemes, we have estimated the practical execution time for different sequential combinations of p, q. This results in different public keys (n) and private keys (d). Figure 8a shows the execution time versus the public key from 143 (11, 13) to 186,623 (431, 433), up to 20 data points. This experiment was performed with a data rate of 19,200 kbps. A similar experiment was performed to check the effective implementation of RSA at various speeds, and as shown in Figure 8b, the values chosen for p, q are 47, 53 for a public key value of 2491. The two experiments show that the systematic variation suggests the robustness of the RSA implementation. After that, we compared the originally sent data and the received data from the UOWC system to estimate the error fraction without RSA encryption and with RSA encryption. This comparative study provided information on communication reliability. Figure 9a presents the error fraction versus data rate without RSA encryption applied, and Figure 9b shows the error fraction versus different modulation schemes with RSA encryption. In both cases, there is an increase in the error fraction at higher data rates. RSA encryption highlights the additional challenges introduced by encryption, due to processing overhead and synchronization issues. Together, these subfigures demonstrate the trade-offs between encryption strength and transmission reliability. This can be overcome by implementing Ethernet protocols. 4.3. Integration of Forward Error Correction codes with RSA Encryption Despite offering higher security to the data, RSA encryption is prone to a higher error fraction. One solution to address this issue is to implement mitigation techniques such as error correction codes alongside modulation schemes to optimize or minimize errors. To investigate the same, we have employed five forward error correction codes like Repeat Codes, Hamming Codes, BCH Codes, and Reed-Solomon Codes along with encryption and modulation techniques. We choose a data rate of 19.2 kbps and p, q as 47, 53 to conduct initial experiments. Figure 10 shows the initial results of Forward Error Correction with RSA encryption across various modulation schemes. In Figure 10a, the execution time is plotted against different FEC codes, while Figure 10b illustrates the increase in data size resulting from the implementation of FEC. The findings indicate that more complex FEC codes, like Reed-Solomon and BCH, significantly increase execution times due to their computational demands, especially when paired with encryption. Figure 10b shows the execution size with various error correction codes along with RSA encryption. There is an increase in the file size of the data with the error correction codes. It is more suitable for PPM modulation and represents a mere increase over OOK schemes, whereas the introduction of differential schemes like DPIM has further reduced the size, offering an advantage over other pulse modulation schemes. After proving the basic RSA encryption with modulation and encoding formats, a systematic study was conducted to investigate the effect of encryption strength. For the same, we used a combination of “p, q” to generate various public keys from 143 (11, 13) to 186,623 (431, 433) up to 20 data points and estimated the execution time for all error correction codes for all modulation separately. An in-depth analysis of the execution time required for RSA encryption when combined with different Forward Error Correction codes across various modulation schemes is provided in Figure 11. The graphs illustrate the relationship between the size of the RSA public key and execution time for various modulation schemes like OOK-NRZ, OOK-RZ, PPM, and DPIM. In the NRZ case, the execution time consistently increases with larger public key sizes. This trend shows the complexity of FEC codes like Reed-Solomon compared to simpler ones, such as Repeat Codes. Similarly, RZ modulation shows a steady rise in execution time, with its synchronization advantages somewhat mitigating the overhead introduced by FEC codes. However, more complex codes like BCH still lead to significant delays. In the case of PPM, which offers better noise immunity, the execution time remains relatively manageable, although the impact of robust FEC codes becomes more evident as public key sizes increase. Lastly, DPIM, known for its lower power requirements, also demonstrates consistent performance, balancing efficiency and error correction overhead effectively. Across all modulation schemes, the trade-offs between encryption strength, error correction, and computational efficiency are clear, emphasizing the importance of optimizing these factors for secure and reliable underwater optical communication. 4.4. Performance Analysis of UWOC System with Forward Error Correction Codes and RSA Encryption After the successful implementation of the various FECs, modulation schemes, and RSA encryption combined, we have saved the data and measured the error fraction in the received file compared to the original sent file. This will give us a clear idea about which modulation scheme, with which error correction, will reduce the error, and where it will increase the error. For this, we have again used a data rate of 19.2 kbps and p, q as 47, 53. The results found show interesting trends and are presented in Figure 12. OOK-NRZ modulation has shown a reduction in error fraction for almost all error correction codes. OOK-RZ has also shown a reduction in error fraction for all FECs except the repeat code 5. The PPM modulation scheme did not contribute to any reduction in error; instead, it increased the error, possibly due to bandwidth inefficiency and strong channel-induced attenuation. DPIM showed minimal impact from FEC implementation. Analysis of the link performance of various Forward Error Correction codes combined with RSA encryption across different modulation schemes is shown in Figure 12. The findings indicate that more robust FEC codes, such as Reed-Solomon and Bose-Chaudhuri-Hocquenghem, result in significantly higher execution times due to their complex algorithms, while simpler codes like Repeat Codes exhibit lower execution times but reduced error correction capability. The error correction effectiveness of these codes reveals that advanced FEC techniques provide flexibility against underwater signal disruptions, ensuring reliability even in adverse conditions, but with the additional load of increased computational overhead due to the larger data sizes due from added parity bits and encryption payloads. Modulation schemes with inherent noise immunity, such as PPM, perform better in terms of both execution time and error correction compared to conventional schemes. The results indicate that the choice of advanced modulation schemes is a good option for the UOWC system.

To conclude, this paper presented a successful integration of RSA encryption and FEC codes with different modulation schemes. It tested the end-to-end data communication in a 4-m UOWC testbed, which can be further extended to several meters with a reasonable increase in intensity. The results were analyzed for various metrics such as execution time, encryption and encoding strengths, and error fraction that evaluates the link performance. This combinational approach improves both data security and communication reliability while also offering flexibility for implementation in dynamic underwater environments. RSA encryption protects sensitive data, while FEC codes correct errors caused by factors such as turbidity and salinity, thereby enhancing data integrity and reducing errors. Link performance tests with different modulation schemes reveal trade-offs between encryption strength, error correction, and computational requirements. More advanced FEC codes, like Reed-Solomon and BCH, offer better error correction but need more processing power, while simpler codes like Repeat codes are less complex but less effective. Studies show that the bit error rate (BER) can be improved by 20 to 40 percent with the inclusion of error correction codes. However, execution time increases nearly fourfold, and the data size (KB) increases by a factor of 16 compared to systems without FEC. In underwater settings, this can be a pivotal and practical solution for implementing the technology in real-life scenarios. There are many opportunities to improve the existing underwater optical wireless communication (UOWC) system proposed in this paper. Lightweight encryption schemes, such as Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and Data Encryption Standard (DES), can reduce computational complexity and enable efficient real-time data transfer in resource-constrained underwater environments. Additionally, we can add an advanced error correction technique, such as turbo codes and concatenated codes, and study its impact on link reliability in highly turbulent conditions characterized by varying turbidity and salinity. An adaptive modulation and coding protocol that dynamically adjusts to environmental fluctuations can also be studied and developed to further optimize the bit error rate (BER) and link performance. We can also extend the system to multi-nodal configurations with Acquisition, Tracking, and Pointing (ATP) mechanisms that will facilitate robust underwater communication networks for defence and surveillance applications. Moreover, experimental validation over longer channel lengths under controlled oceanic conditions and the integration of deep learning-based signal detection techniques will strengthen the system’s applicability in real-world underwater scenarios, ensuring secure and reliable communication in dynamic environments.

| 1GS | One Guard Slot |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| ATP | Acquisition, Tracking, and Pointing |

| BCH | Bose Chaudhuri Hocquenghem |

| BER | Bit Error Rate |

| DES | Data Encryption Standard |

| DPIM | Differential Pulse Interval Modulation |

| FEC | Forward Error Correction |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| KB | Kilobyte |

| Mbps | Megabit per second |

| NGS | No Guard Slot |

| OOK-NRZ | On-Off Keying Non-Return to Zero |

| OOK-RZ | On-Off Keying Return to Zero |

| PPM | Pulse Position Modulation |

| RS | Reed Solomon |

| RSA | Rivest Shamir Adleman |

| TTL | Transistor-Transistor Logic |

| UOWC | Underwater Optical Wireless Communication |

| USB | Universal Serial Bus |

| WDM | Wavelength Division Multiplexing |

Conceptualization and supervision, A.V.R.M.; methodology, D.D.B.C.; validation, A.V.R.M.; formal analysis, D.D.B.C.; investigation, K.P.; resources, A.V.R.M.; data curation, K.P.; design and visualization of figures, K.P. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P. and D.D.B.C.; writing—review and editing, K.P., D.D.B.C. and A.V.R.M.; project administration, A.V.R.M.; funding acquisition, A.V.R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, financial or personal, that could have influenced the work reported in this manuscript.

This work received a grant from the TIDF-IIT Guwahati with the grant number TIH/TD/0408.

All authors acknowledge IIT Guwahati Technology Innovation and Development Foundation and Defence Institute of Advanced Technology for financial and infrastructural support.

Download Supplementary Materials Figures S1-S8 and Table S1 here.

[1] S. Li, L. Yang, D. B. Da Costa, and S. Yu, “Performance Analysis of UAV-Based Mixed RF-UWOC Transmission Systems,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 5559–5572, 2021. [CrossRef]

[2] Z. Zeng, S. Fu, H. Zhang, Y. Dong, and J. Cheng, “A Survey of Underwater Optical Wireless Communications,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor., vol. 19, pp. 204–238, 2017. [CrossRef]

[3] L. Zhou, Y. Zhu, and W. Zheng, “Analysis and Simulation of Link Performance for Underwater Wireless Optical Communications,” EAI Endorsed Trans. Wirel. Spectr., vol. 3, p. 153467, 2017. [CrossRef]

[4] A. S. Mohammed, S. A. Adnan, M. A. A. Ali, and W. K. Al-Azzawi, “Underwater wireless optical communications links: Perspectives, challenges and recent trends,” J. Opt. Commun., vol. 45, pp. 937–945, 2022. [CrossRef]

[5] L. J. Johnson, F. Jasman, R. J. Green, and M. S. Leeson, “Recent advances in underwater optical wireless communications,” Underwater Technol., vol. 32, pp. 167–175, 2014. [CrossRef]

[6] L. K. Gkoura, G. D. Roumelas, H. E. Nistazakis, H. G. Sandalidis, A. Vavoulas, A. D. Tsigopoulos, et al. Underwater Optical Wireless Communication Systems: A Concise Review. Turbulence Modelling Approaches IntechOpen: London, 2017. [CrossRef]

[7] I. U. Khan, B. Iqbal, L. Songzou, H. Li, G. Qiao, and S. Khan, “Full-duplex Underwater Optical Communication Systems: A Review,” in Proceedings of 18th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technologies, IBCAST 2021, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2021, pp. 886–893. [CrossRef]

[8] A. S. Alatawi, “A Testbed for Investigating the Effect of Salinity and Turbidity in the Red Sea on White-LED-Based Underwater Wireless Communication,” Appl. Sci., vol. 12, p. 9266, 2022. [CrossRef]

[9] S. Chaudhary, A. Sharma, S. Khichar, S. Shah, R. Ullah, A. Parnianifard, et al., “A Salinity-Impact Analysis of Polarization Division Multiplexing-Based Underwater Optical Wireless Communication System with High-Speed Data Transmission,” J. Sens. Actuator Netw., vol. 12, p. 72, 2023. [CrossRef]

[10] S. Kumar, S. Prince, J. V. Aravind, and S. Kumar G, “Analysis on the effect of salinity in underwater wireless optical communication,” Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol., vol. 38, pp. 291–301, 2020. [CrossRef]

[11] A. Rani and A. Kumar, “Study on scattering models for UWOC channel using monte carlo simulation,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics, IC3I 2018, Greater Noida, India, 2018, pp. 198–205. [CrossRef]

[12] Y. Weng, Y. Guo, O. Alkhazragi, T. K. Ng, J. H. Guo, and B. S. Ooi, “Impact of turbulent-flow-induced scintillation on deep-ocean wireless optical communication,” J. Light. Technol., vol. 37, pp. 5083–5090, 2019. [CrossRef]

[13] H. M. Oubei, E. Zedini, R. T. Elafandy, A. Kammoun, T. K. Ng, M. S. Alouini, and B. S. Ooi, “Efficient Weibull Channel Model for Salinity Induced Turbulent Underwater Wireless Optical Communications,” arXiv, 2016. [CrossRef]

[14] M. A. A. Ali, “Comparison of modulation techniques for underwater optical wireless communication employing APD receivers,” Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., vol. 10, pp. 707–715, 2015. [CrossRef]

[15] G. Jeong and S. M. Kim, “Performance Evaluation of Underwater Optical Wireless Communication Depending on the Modulation Scheme,” Curr. Opt. Photon., vol. 6, pp. 39–43, 2022. [CrossRef]

[16] A. Hamilton, W. O. Popoola, E. Guler, and C. T. Geldard, “An Empirical Comparison of Modulation Schemes in Turbulent Underwater Optical Wireless Communications,” J. Light. Technol., vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 2000–2007, 2022. [CrossRef]

[17] S. Jain, B. C. D. Devappa, K. Pawar, and A. V. R. Murthy, “Feasibility analysis of modulation formats in different seawater types and practical implementation on underwater optical communication testbed,” J. Opt. (India), 2024. [CrossRef]

[18] H. B. Mangrio, A. Baqai, F. A. Umrani, and R. Hussain, “Effects of Modulation Scheme on Experimental Setup of RGB LEDs Based Underwater Optical Communication,” Wirel. Pers. Commun., vol. 106, pp. 1827–1839, 2019. [CrossRef]

[19] C. Gabriel, M. A. Khalighi, S. Bourennane, P. Leon, and V. Rigaud, “Investigation of suitable modulation techniques for underwater wireless optical communication,” in 2012 International Workshop on Optical Wireless Communications, IWOW 2012, Pisa, Italy, 2012. [CrossRef]

[20] Y. Song, W. Lu, B. Sun, Y. Hong, F. Qu, J. Han, et al., “Experimental demonstration of MIMO-OFDM underwater wireless optical communication,” Opt. Commun., vol. 403, pp. 205–210, 2017. [CrossRef]

[21] H. M. Oubei, J. R. Duran, B. Janjua, H. Y. Wang, C. T. Tsai, Y. C. Chi, et al., “48 Gbit/s 16-QAM-OFDM transmission based on compact 450-nm laser for underwater wireless optical communication,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, p. 23302, 2015. [CrossRef]

[22] G. Tzimpragos, C. Kachris, I. B. Djordjevic, M. Cvijetic, D. Soudris, and I. Tomkos, “A Survey on FEC Codes for 100 G and beyond Optical Networks,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor., vol. 18, pp. 209–221, 2016. [CrossRef]

[23] X. Xu, Y. Li, P. Huang, M. Ju, and G. Tan, “BER Performance of UWOC with APD Receiver in Wide Range Oceanic Turbulence,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 25203–25218, 2022. [CrossRef]

[24] S. A. Adnan, H. A. Hassan, A. Alchalaby, and A. C. Kadhim, “Experimental study of underwater wireless optical communication from clean water to turbid harbor under various conditions,” Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics, vol. 16, pp. 219–226, 2021. [CrossRef]

[25] M. M. Joudha, J. K. Hmood, and S. A. Adnan, “Performance Analysis of Underwater Optical Communication System in Turbulent Link,” Eng. Technol. J., vol. 41, pp. 1082–1090, 2023. [CrossRef]

[26] R. Puri and K. Ramchandran, “Multiple description source coding using forward error correction codes,” in Conference Record of the Thirty-Third Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers (Cat. No.CH37020), Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1999, pp. 342–346. [CrossRef]

[27] A. Leven and L. Schmalen, “Status and recent advances on forward error correction technologies for lightwave systems,” J. Light. Technol., vol. 32, pp. 2735–2750, 2014. [CrossRef]

[28] S. L. S. Narayanan, B. C. D. Devappa, K. Pawar, S. Jain, and A. V. R. Murthy, “Implementation of forward error correction for improved performance of free space optical communication channel in adverse atmospheric conditions,” Results Opt., vol. 16, p. 100689, 2024. [CrossRef]

[29] A. E. Yousif, M. H. Al-Jammas, and A. S. Abdulaziz, “Progress in MIMO Channel Coding Methodologies: An Extensive Overview and Comparative Evaluation,” Lect. Notes Netw. Syst., vol. 1138, pp. 373–389, 2024. [CrossRef]

[30] F. Rahman, “Aplikasi Kendali Kesalahan pada Jaringan Komputer dengan Menggunakan Metode ARQ (Automatic Repeat Request),” Al Ulum J. Sains Dan Teknol., vol. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

[31] M. Kumar, “Advanced RSA cryptographic algorithm for improving data security,” Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput., vol. 729, pp. 11–15, 2018. [CrossRef]

[32] U. Somani, K. Lakhani, and M. Mundra, “Implementing digital signature with RSA encryption algorithm to enhance the data security of cloud in cloud computing,” in 2010 1st International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing, PDGC-2010, Solan, India, 2010, pp. 211–216. [CrossRef]

[33] P. M. Aiswarya, A. Raj, D. John, L. Martin, and G. Sreenu, “Binary RSA encryption algorithm,” in 2016 International Conference on Control Instrumentation Communication and Computational Technologies, ICCICCT, Kumaracoil, India, 2016, pp. 178–181. [CrossRef]

[34] Q. Zhang, “An overview and analysis of hybrid encryption: The combination of symmetric encryption and asymmetric encryption,” in Proceedings-2021 2nd International Conference on Computing and Data Science, CDS 2021, Stanford, CA, USA, 2021, pp. 616–622. [CrossRef]

[35] H. T. Sihotang, S. Efendi, E. M. Zamzami, and H. Mawengkang, “Design and Implementation of Rivest Shamir Adleman’s (RSA) Cryptography Algorithm in Text File Data Security,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1641, p. 012042, 2020. [CrossRef]

[36] R. L. Rivest, A. Shamir, and L. Adleman, “A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems,” Commun. ACM, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 120–126, 1978. [CrossRef]

[37] J. Xu, M. A. Kishk, Q. Zhang, and M. S. Alouini, “Three-Hop Underwater Wireless Communications: A Novel Relay Deployment Technique,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 13, pp. 13354–13369, 2023. [CrossRef]

[38] A. G. Mohamed, S. A. A. El-Mottaleb, M. Singh, H. Y. Ahmed, M. Zeghid, W. M. Abdulkawi, et al., “Chaos Fractal Digital Image Encryption Transmission in Underwater Optical Wireless Communication System,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 117541–117559, 2024. [CrossRef]

[39] S. Afifah, J. K. Wei, L. Marlina, S. K. Liaw, P. J. Lee, and C. H. Yeh, “Performance evaluation of multi-wavelength visible light underwater optical communication,” Opt. Lasers Eng., vol. 192, p. 109026, 2025. [CrossRef]

[40] X. Dong, K. Zhang, C. Sun, J. Zhang, A. Zhang, and L. Wang, “Towards 250-m gigabits-per-second underwater wireless optical communication using a low-complexity ANN equalizer,” Opt. Express, vol. 33, p. 2321, 2025. [CrossRef]

[41] K. Zhang, C. Sun, W. Shi, J. Lin, B. Li, W. Liu, et al., “Turbidity-tolerant underwater wireless optical communications using dense blue–green wavelength division multiplexing,” Opt. Express, vol. 32, p. 20762, 2024. [CrossRef]

[42] R. Jiang, C. Sun, L. Zhang, X. Tang, H. Wang, and A. Zhang, “Deep learning aided signal detection for SPAD-Based underwater optical wireless communications,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 20363–20374, 2020. [CrossRef]

[43] Z. Chen, X. Tang, C. Sun, Z. Li, W. Shi, H. Wang, et al., “Experimental Demonstration of over 14 AL Underwater Wireless Optical Communication,” IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett., vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 173–176, 2021. [CrossRef]

[44] P. Dwivedy, V. Dixit, and A. Kumar, “Cooperative VLC system using OOK modulation with imperfect CSI,” Phys. Scr., vol. 98, p. 25509, 2023. [CrossRef]

[45] S. Luo, M. Miao, and X. Li, “A multi-dimensional modulation format for spectral efficiency improvement of PPM system and its BER performance analysis in free-space optical communication,” J. Opt., p. 27, 2025. [CrossRef]

[46] Z. Ghassemlooy and A. R. Hayes, “Digital pulse interval modulation for IR communication systems—a review,” Int. J. Commun. Syst., vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 519–536, 2000. [CrossRef]

[47] A. K. Majumdar, A. A. Toshimitsu, U. Asakura, J. W. Theodor Hänsch, G. Kamiya, J. Ferenc Krausz, et al. Springer Series in Optical Sciences Springer: Berlin, 2024. [CrossRef]

[48] N. E. Miroshnikova and A. I. Sattarova, “Analysis of Error-Correction Codes Properties for Underwater Optical Communication Systems with OCDM Modulation,” in 2022 Systems of Signal Synchronization, Generating and Processing in Telecommunications, SYNCHROINFO 2022—Conference Proceedings, Arkhangelsk, Russia, 2022. [CrossRef]

[49] A. Elfikky, A. I. Boghdady, A. G. AbdElkader, E. E. Elsayed, K. W. S. Palitharathna, Z. Ali, et al., “Performance analysis of convolutional codes in dynamic underwater visible light communication systems,” Opt. Quantum Electron., vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2024. [CrossRef]

[50] D. Devappa, S. Banerjee, K. Pawar, and A. V. R. Murthy, “Practical realization and performance analysis of Rivest-Shamir-Adleman encryption for secure underwater optical communication,” Next Res., vol. 2, p. 100225, 2025. [CrossRef]

[51] Y. Cai, N. Ramanujam, J. M. Morris, T. Adali, G. Lenner, A. B. Puc, et al., “Performance limit of forward error correction codes in optical fiber communications,” OFC 2001 Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf. Exhibit. Tech. Dig. Postconf. Ed., vol. 2, p. TuF2-T1-3, 2001. [CrossRef]

[52] , “Number Theory - Tristin Cleveland - Google Books, (n.d.),”. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=o-PEDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR15&dq=t+cleveland+number+theory+edtech&ots=cdF5ioiNRT&sig=j7MQTlgAWwQcqYqFsp9Y5_lnKK8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed May 21, 2025)..

[53] H. Kaushal and G. Kaddoum, “Underwater Optical Wireless Communication,” IEEE Access, vol. 4, pp. 1518–1547, 2016. [CrossRef]

[54] I. Ramley, H. M. Alzayed, Y. Al-Hadeethi, M. Chen, and A. Z. Barasheed, “An Overview of Underwater Optical Wireless Communication Channel Simulations with a Focus on the Monte Carlo Method,” Mathematics, vol. 12, p. 3904, 2024. [CrossRef]

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more