APA Style

Saranya Puzhakkal, Piyush Mittal, Kaeshaelya Thiruchelvam. (2025). Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence Synthesis in Healthcare Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0001). https://doi.org/10.69709/ESHC.2025.123254MLA Style

Saranya Puzhakkal, Piyush Mittal, Kaeshaelya Thiruchelvam. "Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Evidence Synthesis in Healthcare Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0001, https://doi.org/10.69709/ESHC.2025.123254.Chicago Style

Saranya Puzhakkal, Piyush Mittal, Kaeshaelya Thiruchelvam. 2025. "Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Evidence Synthesis in Healthcare Connect 1 (2025): 0001. https://doi.org/10.69709/ESHC.2025.123254.

ACCESS

Systematic Review

ACCESS

Systematic Review

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0001

Saranya Puzhakkal

saranya.puzhakkal@hud.ac.uk

Piyush Mittal

piyush.mittal@sharda.ac.in

Kaeshaelya Thiruchelvam

kaeshaelya@imu.edu.my

1 Department of Pharmacy, School of Applied Sciences, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield HD13DH, UK

2 School of Pharmacy, Sharda University, Knowledge Park-III, Greater Noida 201310, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 School of Pharmacy, IMU University, Kuala Lumpur 57000, Malaysia

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 01 Jul 2025 Accepted: 30 Sep 2025 Available Online: 01 Oct 2025 Published: 21 Oct 2025

This study estimated the prevalence of H. pylori infection in India among adults and children with and without gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the 2020 PRISMA guidelines and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024597401). Scientific databases (e.g., MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Google Scholar) were searched to identify English-language articles from India presenting data on H. pylori prevalence. The quality of the included studies was assessed, and prevalence estimates were subsequently pooled using a random-effects model with a 95% confidence interval. The 52 studies included in the analyses were conducted in 15 different states in India, with the majority originating from the state of Uttar Pradesh (23/52). The pooled prevalence of H. pylori among people with GI diseases was 54% (95% CI: 48–60%, n = 11492), compared to 61% (95% CI: 52–69%, n = 1861) among people with no clinically diagnosed GI conditions. The pooled prevalence estimates among children with and without GI diseases were 34% (95% CI: 5–68%, n = 458) and 49% (95% CI: 37–60%, n = 718), respectively. Across regions, the highest prevalence was observed in Rajasthan (70%), whereas the lowest was reported in Gujarat (9%). Since H. pylori infection can lead to many other clinical complications, government initiatives and policies are needed to prevent the spread of the H. pylori pathogen in India.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains a significant global public health concern, with an estimated prevalence of 43.1% reported between 2011 and 2022 [1]. There appears to be a variation in prevalence between countries and regions. The global prevalence of H. pylori infection was approximately 44%, with a higher prevalence of 51% in developing countries compared to 35% in developed countries [2]. Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic spiral-shaped Gram-negative bacterium primarily found in the gastric mucosa [3]. H. pylori has been reported to be associated with chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, and B-cell lymphoma [4]. The outer membrane protein (OMP) aids in adhering H. pylori to the stomach epithelium; the OMP is essential for the attachment and colonization of the stomach. Individuals with H. pylori infection exhibit inflammation of the stomach mucosa, leading to metaplasia, and some individuals may eventually develop gastric cancer because of chronic, long-term infection [5]. The World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies H. pylori as a class I (definite) carcinogen [6]. The transmission of H. pylori between individuals occurs through direct contact, such as via saliva, vomitus, or faeces. H. pylori can also spread through contaminated food or water [7]. The rate of H. pylori infection in children is high in developing countries. Epidemiological and microbiological investigations have demonstrated both waterborne transmission and person-to-person transmission within families. However, the exact transmission mode of H. pylori infection remains unknown [8]. H. pylori treatment typically consists of a triple-therapy regimen that includes a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics, amoxicillin combined with either clarithromycin or metronidazole, administered for seven days [9]. There appears to be a lack of meta-analysis presenting the true pooled (overall) prevalence of H. pylori in India, the second-largest population in the world. Multiple global reports have documented the prevalence of H. pylori in India; however, the available estimates contain several limitations. For example, a 2012 Western perspective on H. pylori prevalence in India reported that the prevalence may be 80% or higher in rural areas of the Indian subcontinent, based on a 1997 position paper on H. pylori in India [10]. A 2017 global systematic review reported the prevalence of H. pylori in India based on data from two studies (published in 1994 and 2002) with a total sample size of approximately 400 participants [3]. Another global report on the prevalence of H. pylori published in 2018 reported H. pylori prevalence in India based on a small sample size [4]. These prevalence estimates may not be accurate due to the small sample size and exclusion of individuals with gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. Therefore, this meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection across different regions of India, in various gastrointestinal diseases, and among both adults and children, based on a sufficient number of original studies. This meta-analysis also examines the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with and without other gastrointestinal disorders, to determine whether having any gastrointestinal disorder increases the risk of getting H. pylori infection.

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (Reference number: CRD42024597401). This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the 2020 PRISMA guidelines (see the PRISMA checklist in Table S1) [11]. 2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy A search strategy was developed using a combination of Medical Subject Headings and free text search terms, including those related to H. pylori. A prevalence search was then performed in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Google Scholar. Search terms including ‘Helicobacter pylori or H. pylori’, ‘prevalence or incidence or epidemiology or frequency or occurrence or statistics,’ and ‘India’ were used. All original studies published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2024 were included in the analysis. Reference lists for articles found during the search, as well as relevant review articles, were included and subjected to the same eligibility assessment. 2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Original studies (e.g., cross-sectional studies) assessing the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with or without gastrointestinal (GI) diseases were included in this review. These studies were published in English between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2024. They presented prevalence data for any age group in India and detected H. pylori using any recognized diagnostic tests. The exclusion criteria include non-original articles (such as reviews, experimental studies, clinical trials, animal studies, meta-analyses, case reports, editorials, letters, commentaries, abstracts, and conference proceedings), articles in languages other than English, duplicate articles, and studies conducted on non-Indians or Indians residing abroad. 2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction The primary investigators [SP and KT] screened titles and abstracts of articles reporting the prevalence of H. pylori infection and independently evaluated them based on the inclusion criteria. The two investigators independently assessed the eligibility of full-text articles for inclusion in the proposed analysis. Studies irrelevant to the study aim were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. To ascertain eligibility, the full texts of the remaining studies were evaluated. Studies were sorted using the above criteria, and information was then retrieved and entered into a Microsoft Excel® 2017 spreadsheet. The following information was obtained from studies conducted in specific regions: overall participant count, population age range, study design, concurrent disorders, methods used to detect H. pylori, whether patients were symptomatic or asymptomatic, and details about any treatment provided. 2.4. Quality Assessment The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS), modified for use in cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies, was employed to assess the quality of the included papers. The NOS was selected because it is a validated, quick, and adaptable tool. 2.5. Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis Subgroup analyses were conducted among adult populations with GI diseases, including gastric cancer, dyspepsia, and ulcers. We also estimated the pooled point prevalence of H. pylori among people with no GI diseases. “Gastric cancer” was defined as the development of malignant cells in the stomach lining. Dyspepsia, commonly referred to as indigestion, was defined as discomfort in the upper abdomen, including symptoms such as abdominal pain and early satiety. The “peptic ulcer” was defined as an open sore that forms on the interior lining of the stomach and the upper small intestine. In addition, the development of an ulcer in the stomach was defined as a “gastric ulcer”. In contrast, developing an ulcer in the duodenum was defined as a “duodenal ulcer”. The age group for children was defined as ages between 0 months and 15 years. All statistical analyses, except for odds ratio (OR) and risk ratio (RR), were performed using MetaXL version 5.3. Our meta-analysis utilised point prevalence data from observational studies, defined as the proportion of a population with the characteristic at a specific point in time. Since methodological differences may impact prevalence estimates, we pooled prevalence data only from observational studies and excluded data from other designs for consistency and accuracy. Subgroup analyses were conducted when four or more studies were available. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in various regions of India was analysed separately. The data from case-control studies were analysed separately for each group. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in each study was pooled using a random effects model to estimate the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in India. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the Cochrane Q and I2 statistics with a cut-off score of 50.0% and the χ2 test with a p-value < 0.10 as the threshold for statistically significant heterogeneity. A funnel plot was used to identify publication bias.

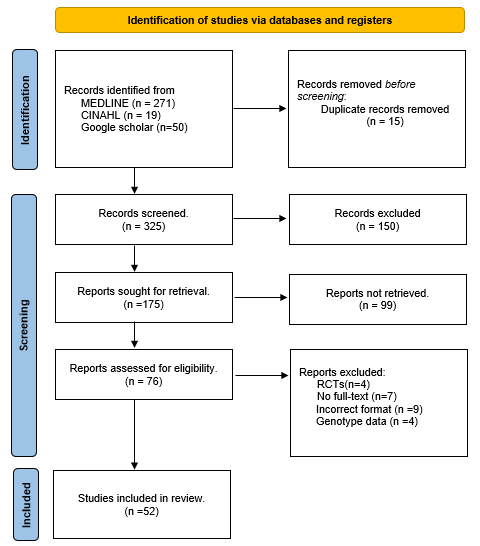

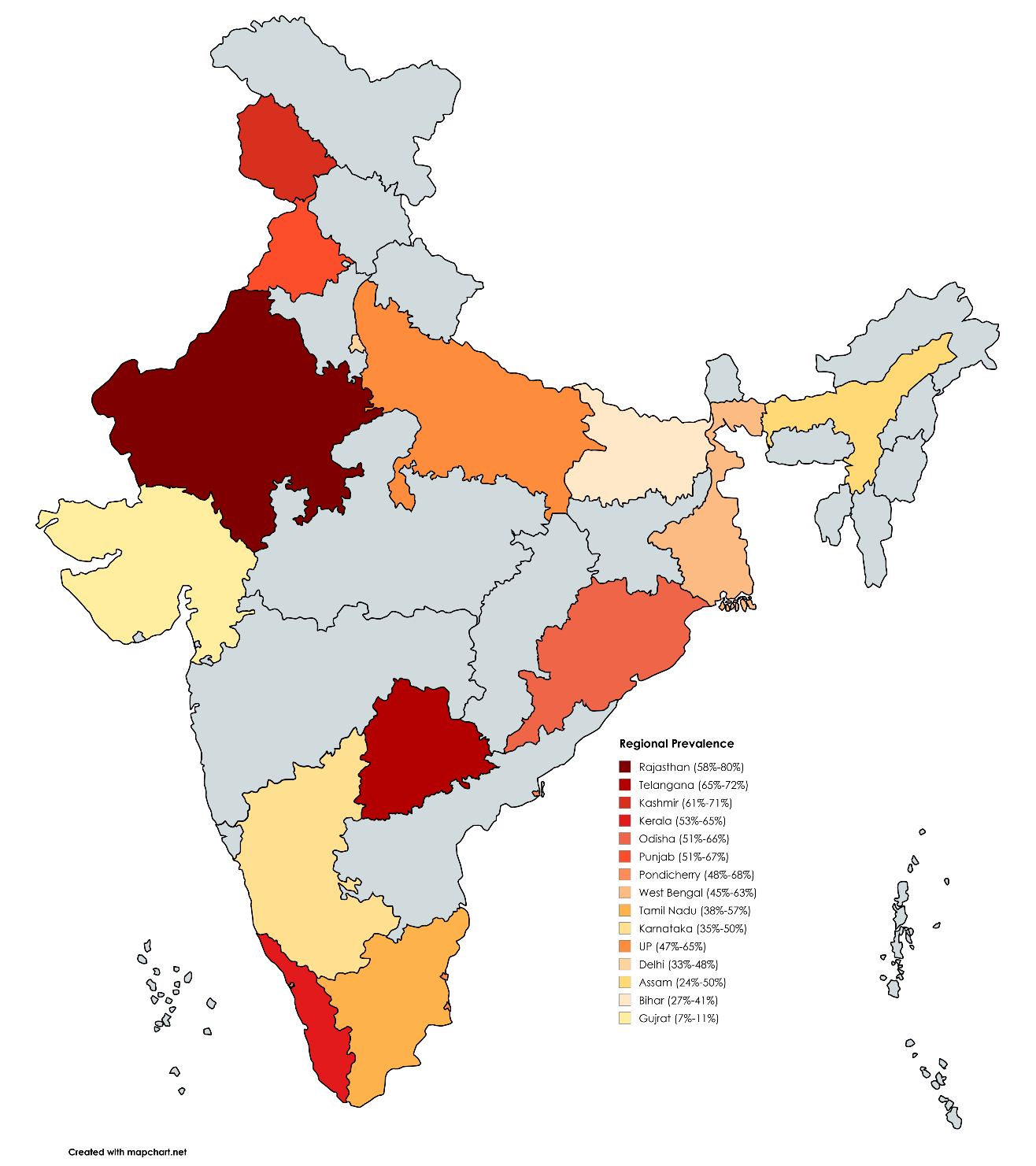

Our search yielded 340 unique records from the databases. After removing duplicate records and applying eligibility criteria, 76 records were considered for full-text review. Of 76 records, 24 articles were excluded due to the lack of genotype data (n = 4), unavailability of full text and author contact details (n = 7), and studies with no prevalence data (n = 9). Four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were excluded from this review because the number of available studies was insufficient to conduct a separate meta-analysis. The final analyses included 52 studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], which produced 72 datasets. The PRISMA flow diagram is present in Figure 1. Many studies employed multiple methods to detect H. pylori. Among the diagnostic tests, a rapid urea breath test (n = 31) [14,15,16,17,19,23,28,29,32,33,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,47,49,50,51,52,54,56,57,58,59,60] was the most frequently used test to diagnose H. pylori, followed by polymerase chain reactions (n = 24) [15,18,20,25,26,31,32,33,36,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,48,49,50,51,53,54,62,63], histopathology (n = 21) [14,15,16,24,32,33,36,38,41,42,44,46,47,48,49,52,54,55,56,61,62], culture test (n = 14) [12,15,16,27,28,32,33,36,42,44,46,48,54,62] and ELISA test (n = 5) [13,34,35,43,60]. Serology (n = 4) [28,39,55,59], Giemsa staining (n = 2) [22,30], biochemical test (n = 1) [39], HpSA test (n = 1) [57], and antibody titer ((n = 1) [21] were some other tests used to detect the infection (Table 1). Summary of studies included in the review. 3.1. Quality Assessment The majority of the studies included (41/52) were cross-sectional or descriptive studies. The majority of them (n = 24) received a score of 8 out of 9, followed by scores of 7 (n = 11), 9 (n = 7), and 6 (n = 3). Most of the case-control studies scored 8 (n = 5), followed by 9 (n = 1), 7 (n = 1), and less than 7 (n = 3). Only one of the included studies was a cohort study, and it received a score of 8 (see Supplementary Tables S2–S4). 3.2. National and Regional Prevalence of H. pylori Infection 11,492 individuals with gastrointestinal diseases were included in this review, which determined a pooled prevalence of H. pylori of 54% (95% CI: 48–60%) (see Supplementary Figure S1). Among 1861 people with no clinically diagnosed GI conditions, the pooled prevalence of H. pylori was 61% (95% CI: 52–69%). Seven studies, with a combined sample size of 2263, did not mention any GI diseases (see Table 1). The pooled prevalence of H. pylori among this population was 55% (95% CI: 42–67%). The pooled prevalence for these two groups combined was 58% (95% CI: 51–65%), as shown in Figure 2. The studies included in this review were conducted in 15 different states in India. The majority of studies were from Uttar Pradesh (23/52), followed by eight studies in Delhi, seven in Telangana, six in Pondicherry, five in West Bengal, five in Karnataka, four in Tamil Nadu, two studies each in Kashmir, Kerala, and Rajasthan, and only one study each in Bihar, Gujarat, Odisha, Punjab and Shillong (see Table 1). Nine out of 15 states reported a prevalence greater than 50.0% among patients with or without gastrointestinal diseases. The H. pylori infection cases were highest in Rajasthan (Mean: 69%, Range: 58–80%), followed by the state of Telangana (Mean: 68.5%, Range: 65–72%), Kashmir (Mean: 66.0%, Range: 61–71%), Kerala (Mean: 59.0%, Range:53–65%), Odisha (Mean: 59.0%, Range: 51–66%), Punjab (Mean: 59.0%, Range: 51–67%), Pondicherry (Mean: 58.0%, Range: 48–68%), West Bengal (Mean: 54%, Range: 45–63%), Tamil Nadu (Mean: 47.5%, Range: 35–50%), Karnataka (Mean: 42.5%, Range: 35–50%), Uttar Pradesh (Mean: 56%, Range: 47–65%), Delhi (Mean: 40.5%, Range: 33–48%), Assam (Mean: 37%, Range: 24–50%), Bihar (Mean: 34%, Range: 27–41%) and Gujarat (Mean: 9%, Range: 7–11%) (Figure 3). 3.3. H. pylori Infection Among People with GI Diseases A total of 12 studies reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection in individuals with ulcers [15,19,31,39,40,41,44,45,48,53,57,60] with an overall prevalence estimated as 70% (95% CI 53–85%) (Figure 4). The highest prevalence was reported for individuals with duodenal ulcer (76%, 95% CI: 42–100%), followed by individuals with peptic ulcer (68%, 95% CI: 46–86%), and individuals with gastric ulcer (58%, 95% CI: 5385%). 21 studies determined the prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with dyspepsia [15,16,18,23,24,25,27,34,35,40,41,43,44,46,49,53,55,56,60,61,62]. The overall prevalence of H. pylori among individuals with dyspepsia was 52% (95% CI: 46–59%). There was a total of 7 studies that reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with gastric cancer. The overall prevalence was 63% (95% CI: 55–71%) (Figure 5). 3.4. Prevalence of H. pylori Infection Among Children Seven studies included children, of which two were conducted among individuals without clinically diagnosed gastrointestinal (GI) disease [14,56], and three among those with GI diseases [49,61,67]. In comparison, two studies included children who were diagnosed and not diagnosed with GI diseases [26,58]. The pooled prevalence of H. pylori infection among children with no clinically diagnosed GI diseases was 49% (95% CI: 37–60%) (Figure 6), whereas the pooled prevalence among children with GI diseases was 34% (95% CI: 5–68%).

Study Name (Year)

Year

Sample Size

Population and Region

Study Design

Diseases

H. pylori Detection Method

Symptomatic/Asymptomatic

Numbers Infected

Treatment Provided

Singh et al. (2023) [12]

2023

176

Adult/Bihar

Descriptive study

Patient underwent endoscopy

Culture test

Asymptomatic

60

NA

Laya et al. (2022) [13]

2022

155

Adult/Pondicherry

Case control study

A. Periampullary/Pancreatic cancer (48/61)

B. Extra-abdominal benign condition (72/94)ELISA test

Asymptomatic

120

NA

Varuna et al. (2022) [14]

2022

152

Adult/Pondicherry

Prospective cohort study

Oesophageal varices bleeding

Rapid urease testing and Histopathological examination

Asymptomatic

73

NA

Shetty et al (2021) [15]

2021

374

Adult/Manipal

Prospective cross-sectional study

A. Functional dyspepsia (117/271)

B. Peptic ulcer (41/82)

C. Gastric cancer (11/20)Histopathological examination, Culture test, Rapid urease test, and PCR

Symptomatic

169

NA

Wani et al. (2018) [16]

2018

196

Adult/Kashmir

Cross-sectional hospital-based study

Dyspepsia

Histopathological examination, Rapid Urease test, and Culture test

Asymptomatic

95

Clarithromycin, Metronidazole, Tetracycline, and Quinolones

Mukherjee et al. (2020) [17]

2020

863

Adult/Mizoram

Cross-Sectional study

Gastritis

Rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

475

NA

Vadivel et al. (2018) [18]

2018

147

Adult/Chennai

Cross-sectional study

Dyspepsia

PCR

Asymptomatic

62

NA

Sultana et al. (2014) [19]

2014

255

Adult/West Bengal

Case control study

A. Gastric cancer (80/120)

B. Healthy control (75/135)Rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

155

NA

Pandey et al. (2018) [20]

2018

156

Adult/Allahabad

Observational study

A. Cancer (34/65)

B. Pre cancer (28/30)

C. Normal (37/61)PCR

Asymptomatic

156

NA

Tsuchiya et al. (2018) [21]

2018

200

Adult/Lucknow

Hospital-based case-control study

A. Gall bladder cancer with gallstones (41/100)

B. Cholelithiasis (42/100)Plasma H. pylori antibody titer

Asymptomatic

83

NA

Narang et al. (2017) [22]

2017

646

Children (1–8 years)/Delhi

Prospective, Cross-sectional study

A. Celiac disease (37/324)

B. Without Celiac disease (161/322)Giemsa staining

Asymptomatic

198

NA

Dutta et al. (2017) [23]

2017

1000

15 yrs to >50 yrs/Vellore

Prospective study

Dyspepsia

Rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

419

NA

Satpathi et al. (2017) [24]

2017

165

15–75 years/Orissa

Prospective study

Dyspepsia

Histopathology, Gram stain, and biopsy urease

Asymptomatic

97

NA

Jeyamani et al. (2018) [25]

2018

165

Adult/Tamilnadu

Observational cross-sectional study

Dyspepsia

PCR

Asymptomatic

61

NA

Qadri et al. (2014) [26]

2014

130

Adult/Kashmir

Descriptive study

Gastric cancer and Gastroduodenal biopsy specimens

PCR

Asymptomatic

104

NA

Pandya et al. (2014) [27]

2014

855

Adult/Gujarat

Descriptive study

Gastritis, Duodenitis, Duodenal/gastric ulcer, and reflux esophagitis

Biopsy specimen culture

Symptomatic

80

Metronidazole, Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, Ciprofloxacin, Tetracycline, Furazolidone, Erythromycin, and Levofloxacin

Nisha et al. (2016) [28]

2016

500

Adult/Kerala

Community-based Cross-sectional study

No disease

Rapid urease test and serological examination

Asymptomatic

345

NA

Pandey et al. (2014) [29]

2014

921

Adult/North India

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

Rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

543

NA

Fujiya et al. (2014) [30]

2014

30

Adult/Hyderabad

Prospective cross-sectional two-centre design study

Not mentioned

Hematoxylin-cosin and Giemsa combined with immunostaining using antibodies against H. pylori

Asymptomatic

0

NA

Ghosh et al. (2012) [31]

2012

854

Adult/Hyderabad

Descriptive study

A. Total population (579/854)

B. Smokers (682/768)PCR

Asymptomatic

579

NA

Shukla et al. (2013) [32]

2013

200

Adult/Lucknow

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

Rapid urease test, Culture test, Histopathology, and H. pylori-specific ureA PCR

Asymptomatic

105

NA

Bansal et al. (2012) [33]

2012

49

Adult/Delhi

Descriptive study

Benign biliary tract disease

Culture test, Bile and Tissue PCR, Histopathology, and Rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

16

NA

Kashyap et al. (2012) [34]

2012

100

Adult/Delhi

Case control study

Dyspepsia

ELISA test

Asymptomatic

10

NA

Tripathi et al. (2011) [35]

2011

309

Adult/Lucknow

Case control study

A. Gastric cancer (32/52)

B. Functional dyspepsia (25/36)

C. Peptic ulcer (/22/37)ELISA test

Asymptomatic

79

NA

Shukla et al. (2011) [36]

2011

200

Adult/Lucknow

Case control study

A. Peptic ulcer disease (41/50)

B. Non ulcer disease (46/100)

C. Gastric Cancer (31/50)Rapid urease test, Culture, Histopathology, PCR, and Q-PCR

Asymptomatic

118

NA

Goenka et al. (2011) [37]

2011

128

Adult/Kolkata

Single-centre cross-sectional study

A. Gastric ulcer (40/74)

B. Duodenal ulcer (38/54)Rapid urease breath test and C-Urea breath test

Asymptomatic

78

NA

Shukla et al. (2011) [38]

2011

120

Adult/Lucknow

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

RUT, Culture test, Histopathology, H. pylori specific ureC PCR, and Q-PCR

Asymptomatic

65

NA

Mishra et al. (2011) [39]

2011

108

Adult/Varnasi

Prospective case control study

A. Gallstone disease (18/54)

B. Gall bladder cancer (24/54)Rapid urease test, Biochemical test, Histology, culture, serology, PCR, and Partial DNA sequencing

Asymptomatic

42

NA

Singh et al. (2009) [40]

2009

108

Adult/Varanasi

Descriptive study

Duodenal or Gastric ulcer/Gastritis/Gastric adenocarcinoma/non-ulcer dyspepsia

PCR

Asymptomatic

68

Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, Metronidazole, and Tetracycline

Prasad et al. (2008) [41]

2008

348

Adult/Uttar Pradesh

Descriptive study

Gastric adenocarcinoma, Peptic ulcer disease, and non-ulcer dyspepsia

Rapid urease test, Histopathology, and H. pylori-specific ureA PCR

Asymptomatic

204

NA

Chakravorty et al. (2008) [42]

2008

310

Adult/Kolkata

Case control study

Gastroenterological problems

Rapid urease test, Histopathology, and Culture test

Asymptomatic

117

NA

Mishra et al. (2008) [43]

2008

52

Adult/Varanasi

Descriptive study

Dyspepsia

ELISA Test, PCR, and antigen-based detection in stool

Asymptomatic

40

Clarithromycin 500 mg, Amoxicillin 1g, and Omeprazole 20 mg were given twice a day for 14 days

Saxena et al. (2008) [44]

2008

348

Adult/Lucknow

Descriptive study

Gastric adenocarcinoma, Peptic ulcer disease, and non-ulcer dyspepsia

Rapid urease test, Culture test, Histopathology, and PCR

Asymptomatic

204

NA

Mishra et al. (2008) [45]

2008

245

0-60years/Banaras

Descriptive study

No disease

PCR

Asymptomatic

A. Children (0–16 years)-132/137

B. Adult (17–60 years) 108/108NA

Sharma et al. (2014) [46]

2014

84

Adult/Ladakh

Cross-sectional study

Dyspepsia

Histopathology and culture test

Asymptomatic

78

NA

Yadav et al. (2008) [47]

2008

136

Adult/Jaipur

Case control study

A. Chronic idiopathic urticaria (48/68)

B. Chronic Urticaria (46/68)Rapid Urease and Histopathology

Asymptomatic

94

NA

Tiwari et al. (2008) [48]

2008

92

Adult/Hyderabad

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

Culture test, PCR, and histopathology

Asymptomatic

72

NA

Arachchi et al. (2007) [49]

2007

166

Adult/Delhi

Descriptive study

A. Duodenal ulcer (36/96)

B. Functional dyspepsia (16/70)Rapid urease test, Histology, and PCR

Asymptomatic

56

NA

Ahmed et al. (2007) [50]

2007

500

Adult/Hyderabad

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

Rapid urease test and PCR

Asymptomatic

400

NA

Ahmed K S et al. (2006) [51]

2006

400

Adult/Hyderabad

Descriptive study

Not mentioned

Rapid urease test and PCR

Symptomatic

246

NA

Biswal et al. (2005) [52]

2005

76

2 months to 2 years/Pondicherry

Hospital-based prospective study

Recurrent pain abdomen

Histopathological studies and rapid urease test

Asymptomatic

34

NA

Tiwari et al. (2005) [53]

2005

120

Adult/Hyderabad

Descriptive study

Duodenal ulcer, Gastric ulcer, and non-ulcer dyspepsia

PCR

Asymptomatic

120

NA

Singh et al. (2006) [54]

2006

240

Children/Lucknow

Prospective study

A. Upper abdominal pain (31/58)

B. No upper abdomen pain (51/182)Rapid urease test, Culture, H. pylori-specific ureA PCR, and Histopathology

Asymptomatic

82

Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, and Omeprazole

Anand et al. (2006) [55]

2006

134

Adult/Kerala

Case control study

Dyspepsia

H. pylori Serology, Rapid urease test, or Histopathology

Asymptomatic

65

NA

Tovey et al. (2004) [56]

2004

359

Adult/Lucknow

Prospective study

A. Duodenal ulcer (137/148)

B. Non ulcer dyspepsia (165/211)Rapid Urease Test and Histopathology

Asymptomatic

302

NA

Shaikh et al. (2005) [57]

2005

86

Children (1–10 years)/Kolkata

Descriptive study

No disease

C-Urea breath test and HpSA test

Asymptomatic

45

NA

Batmanabane et al. (2004) [58]

2004

37

Adult/Pondicherry

Descriptive study

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Rapid urease test and Histology

Asymptomatic

16

NA

Shankar et al. (2003) [59]

2003

49

Adult/Pondicherry

Descriptive study

Hematemesis and or Melena and proved to have erosive gastroduodenitis

Rapid Urease, Histology, and Serology

Asymptomatic

23

NA

Singh et al. (2002) [60]

2002

147

15 Yrs and older/Chandigarh

House-to-house pilot survey (Comparative study)

Dyspepsia

Rapid urease test and ELISA test

Asymptomatic

87

NA

Venkatesan et al. [61]

2024

2998

Adults/Karnataka

Cross-sectional study

Dyspepsia

Histopathology

Asymptomatic

1295

NA

Datta et al. [62]

2024

52

Adults/Shillong

Cross-sectional study

Dyspeptic symptoms

Culture test

Histopathology

RT-PCRAsymptomatic

52

NA

Sruthi et al. [63]

2023

20

Children (3–6 years)/Chennai

Cross-sectional study

Patients visited the Paediatric outpatient clinic

RT-PCR

Asymptomatic

14

NA

![Figure 2: Prevalence of H. pylori infection among people with no clinically diagnosed GI conditions, no GI disease mentioned, and combined [19,20,28,29,30,31,32,36,43,48,50,51,56].](/uploads/source/articles/evidence-synthesis-in-healthcare-connect/2025/volume1/20250001/image002.png)

![Figure 4: Prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with duodenal ulcer (DU), peptic ulcer (PU), gastric ulcer (GU), and combined [15,17,35,36,37,44,49,53,56,59].](/uploads/source/articles/evidence-synthesis-in-healthcare-connect/2025/volume1/20250001/image004.png)

![Figure 5: Prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with dyspepsia and gastric cancer [15,16,18,19,20,23,24,25,26,32,35,43,44,46,49,55,60,61,62].](/uploads/source/articles/evidence-synthesis-in-healthcare-connect/2025/volume1/20250001/image005.png)

![Figure 6: Prevalence of H. pylori infection among children with and without GI diseases [22,43,52,54,57,63].](/uploads/source/articles/evidence-synthesis-in-healthcare-connect/2025/volume1/20250001/image006.png)

The present review is the most updated and recent meta-analysis that determined the prevalence of H. pylori infections in India. This study identified a high prevalence of 54% of H. pylori infections among people with GI diseases and a 61% prevalence among people with no clinically diagnosed GI diseases in India. As expected, the pooled prevalence of H. pylori among individuals with GI diseases such as ulcers, gastric cancer, and dyspepsia was more than 50%. In addition, there was a 49% prevalence of H. pylori among children with no clinically diagnosed GI diseases compared to 34% among children with GI diseases in India. Our findings of a high prevalence of H. pylori in India concur with previous evidence, such as Poddar et al. (2019), who reported a prevalence of H. pylori infection of 60 to 80% in low and middle-income countries [64]. Hooi et al. (2017) reported that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was particularly high in Southern Asia and India, with a prevalence of approximately 64%. However, their findings for India were limited due to the small number of studies and participants [3]. The present review provided more robust findings regarding the number of studies and sample size, and included more recent studies with adequate subgroup analyses. Low and middle-income countries like India depict a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection due to the higher risk of transmission, especially via waterborne transmission of the infection, and in the context of low socioeconomic status (poor sanitation practices and high-density living arrangements) [65]. Waterborne transmission is a common mode of H. pylori transmission in India, likely caused by faecal contamination, particularly in regions where the use of untreated water is prevalent. A study conducted by Ahmed et al. (2007) in South India reported that those who consumed well water were infected more frequently than those who consumed tap water (75% versus 92%). Consumption of municipal tap water was also identified as a source of H. pylori infections in India [50]. In addition, individuals with a low clean water index demonstrated higher rates of H. pylori infection [66]. Socioeconomic status is also a risk factor, where approximately 85% of individuals with lower socioeconomic status had a high prevalence of H. pylori infections. Another common transmission mode in the community is person-to-person, perhaps via the faecal-oral channel or the oral-oral route (via saliva or possibly vomitus). The higher incidence of infection among institutionalized children and adults, along with the clustering of H. pylori cases within households, suggests a person-to-person mode of transmission [50,64,65]. This is further supported by identifying H. pylori DNA in faeces, vomitus, saliva, dental plaque, and stomach juice. Other social risk factors may have resulted in the high prevalence of H. pylori infections in regions around India. These include eating meat, street food, and smoking [66]. Consumption of meat and food prepared under unhygienic conditions was found to be associated with a high prevalence of H. pylori infection [51]. In India, eating street food is common and poses a high risk of contamination if not prepared hygienically. Our findings suggest a lower H. pylori prevalence in children than in adults, i.e., 34% in children with GI diseases and 49% in children without GI diseases. Although previous studies reported a higher prevalence, our findings concur with the seroprevalence studies of Graham et al. (1991) and Gill et al. (1994), who reported that more than 50% of children under the age of 10, and more than 80% of individuals over the age of 20 were infected with H. pylori [67,68]. The high prevalence of the infection among children is due to similar risk factors for older individuals, such as poor sanitation practices and lower socioeconomic status [67,68]. Another study by Poddar et al. (2007) reported findings consistent with ours, indicating a high prevalence of the infection among Indian children, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. However, most infected children did not depict any symptoms throughout their childhood, and only 15% develop peptic ulcer disease as young adults, while 1% develop gastric cancer as they age [69,70]. Our study also found that the regional prevalence of H. pylori infection in India was highest in Rajasthan, at 70%. Rajasthan is a predominantly desert area, and residents may be forced to use unfiltered water due to water scarcity and lower socioeconomic status. A prevalence of more than 60% was also reported in Telangana and Kashmir. Kashmir has been reported to be a highly endemic region for peptic ulcer disease. An earlier study by Romshoo et al. (1999) reported an H. pylori prevalence of 76% in duodenal ulcers and 50% in gastric ulcers in Kashmir. Possible factors that may have contributed to this high prevalence include the following: the Kashmir Valley differs from other states in terms of its dietary habits (i.e., excessive consumption of salt and spices), socio-economic, environmental, and ethnic characteristics, as well as climatic aspects, suggesting other ulcerogenic factors in the endemic disease [71]. Kerala recorded a considerably high H. pylori prevalence of approximately 60%, which may be attributed to the increased occurrence of duodenogastric reflux associated with lifestyle changes, as well as the injudicious use of easily accessible medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [72]. Additionally, the literature suggests a correlation between H. pylori infection and the risk of developing typhoid fever [70]. It is, therefore, crucial to take necessary precautions to curb the transmission of this infection, such as advocating for and adopting better domestic hygiene habits, practising proper waste disposal techniques, and routinely boiling water for consumption [50]. 4.1. Implications for Practice Our meta-analysis reported a high prevalence of H. pylori in India, based on a large number of original studies. Well-documented evidence and data indicate a high prevalence of lower socioeconomic status, poor sanitation practices, and hygiene in India [50,64,65]. Our study carries important implications. In the current Indian context, individuals, particularly those with dyspepsia, ulcers, gastric cancer, and symptomatic cases with clinically undiagnosed ulcers, are reported to have an H. pylori prevalence exceeding 50%. This high prevalence is a serious concern, as evidence suggests that individuals with H. pylori infection can develop a wide array of diseases, including gastric cancer (if not already present). The efficacy of eradication therapy for H. pylori infection is a significant concern. A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding primary antibiotic resistance revealed high resistance to antibiotics such as clarithromycin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and metronidazole. Thyagarajan et al. (2003) further supported these findings in their multicentre study [73]. The availability of antibiotics without prescriptions and the misuse of antibiotics have led to resistance in India. Immediate actions are necessary to prevent the transmission of H. pylori infection in India. Awareness about the transmission of H. pylori infection and its prevention should be raised among communities and regions that are more prone to the infection. 4.2. Strengths and Limitations One of the strengths of this review is that it includes comprehensive and the latest systematic evaluations on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in India. We pooled data according to region, diseases, and age groups to analyse the distribution of H. pylori infection in India. In addition, the prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with conditions such as ulcers, gastric cancer, dyspepsia, and other symptoms was analysed separately. We included studies from various states and regions in India, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the findings to the country as a whole. This review is not without limitations. In the majority of analyses, significant heterogeneity was identified among studies. However, stratification of the pooled prevalence of H. pylori infection according to study design factors allowed for the examination of potential causes of heterogeneity; nonetheless, a sizable amount of variation remained between studies. Most of the included studies did not provide the exact definition of diseases, for instance, gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer. Additionally, various studies have employed different diagnostic tests to detect H. pylori infection.

This meta-analysis provides comprehensive and updated findings on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in India. More importantly, this study provides pooled data on the prevalence of H. pylori in India, which remains unavailable for many states across the country. This study identified a high prevalence of 54% of H. pylori infections among people with GI diseases and a 61% prevalence among people with no clinically diagnosed GI diseases in India. More than 50% was reported for subgroups such as individuals with ulcers, gastric cancer, dyspepsia, and symptomatic individuals with clinically undiagnosed ulcers. The high prevalence of H. pylori in India indicates the need for the government and policymakers alike to conduct awareness campaigns in high-risk regions and states nationwide. Future studies are needed in the high-risk areas of India to identify the causes of the infection and implement necessary strategies to curb its transmission.

CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

DU

Duodenal Ulcer

GI

Gastrointestinal

GU

Gastric Ulcer

H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

OMP

Outer Membrane Protein

OR

Odds Ratio

PU

Peptic Ulcer

RR

Risk Ratio

Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data Extraction, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft: S.P.; Writing—review & editing: P.M.; Approval of final draft, Validation, Writing—review & editing: K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are secondary data obtained from published articles.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

Meta XL version 5.3 was used to make all the forest plots. The Map was made using Map Chart (World Map—Simple | MapChart).

Supplementary material associated with this article has been published online and is available at: https://doi.org/10.69709/ESHC.2025.123254.

[1] Li, Y.; Choi, H.; Leung, K.; Jiang, F.; Graham, D.Y.; Leung, W.K. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection between 1980 and 2022: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 553–564. [CrossRef]

[2] Ahn, H.J.; Lee, D.S. Helicobacter pylori in Gastric Carcinogenesis. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 7, 455–465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3] Hooi, J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [CrossRef]

[4] Zamani, M.; Ebrahimtabar, F.; Zamani, V.; Miller, W.H.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Shokri-Shirvani, J.; Derakhshan, M.H. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: The Worldwide Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 868–876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5] Agudo, S.; Alarcón, T.; Cibrelus, L.; Urruzuno, P.; Martínez, M.J.; López-Brea, M. [High Percentage of Clarithromycin and Metronidazole Resistance in Helicobacter pylori Clinical Isolates Obtained from Spanish Children]. Rev Esp Quimioter 2009, 22, 88–92. [PubMed]

[6] Glupczynski, Y.; Mégraud, F.; Lopez-Brea, M.; Andersen, L. European Multicentre Survey of In Vitro Antimicrobial Resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2001, 20, 820–823. [CrossRef]

[7] Myo Clinic, Helicobacter pylori Infection. (accessed on 26 March 2023).

[8] Aguemon, B.D.; Struelens, M.J.; Massougbodji, A.; Ouendo, E.M. Prevalence and Risk-Factors for Helicobacter pylori Infection in Urban and Rural Beninese Populations. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 611–617. [CrossRef]

[9] NICE Guidelines. (accessed on 23 March 2023).

[10] Graham, D.; Thirumurthi, S. Helicobacter pylori Infection in India from a Western Perspective. Indian J. Méd. Res. 2012, 136, 549–562. [PubMed]

[11] Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

[12] Singh, S.; Sharma, P.; Mahant, S.; Das, K.; Som, A.; Das, R. Analysis of Functional Status of Genetically Diverse OipA Gene in Indian Patients with Distinct Gastrointestinal Disease. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 1–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13] Laya, G.B.; Anandhi, A.; Gurushankari, B.; Mandal, J.; Kate, V. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Periampullary and Pancreatic Cancer: A Case–Control Study. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2022, 53, 902–907. [CrossRef]

[14] Varuna, S.; Sureshkumar, S.; Gurushankari, B.; Archana, E.; Mohsina, S.; Kate, V.; Mahalakshmy, T. Is There an Association between Variceal Bleed and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Cirrhotic Patients with Portal Hypertension?: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Méd. J. 2022, 22, 539. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15] Shetty, V.; Ramachandra, L.; Pai, C.G.; Ballal, M. Profile of Helicobacter pylori cagA & vacA Genotypes and Its Association with the Spectrum of Gastroduodenal Disease. Indian J. Méd. Microbiol. 2021, 39, 495–499. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16] Wani, F.A.; Bashir, G.; Khan, M.A.; Zargar, S.A.; Rasool, Z.; Qadri, Q. Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Mutational Analysis from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kashmir, India. Indian J. Med Microbiol. 2018, 36, 265–272. [CrossRef]

[17] Mukherjee, S.; Madathil, S.A.; Ghatak, S.; Jahau, L.; Pautu, J.L.; Zohmingthanga, J.; Pachuau, L.; Nicolau, B.; Kumar, N.S. Association of Tobacco Smoke–Infused Water (Tuibur) Use by Mizo People and Risk of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8580–8585. [CrossRef]

[18] Vadivel, A.; Kumar, C.P.G.; Muthukumaran, K.; Ramkumar, G.; Balamurali, R.; Meena, R.L.; Venkatasubramanian, S.; Solomon, T.R.; Ganesh, P.; Kumar, S.J. Clinical Relevance of cagA and vacA and Association with Mucosal Findings in Helicobacter pylori-Infected Individuals from Chennai, South India. Indian J. Med Microbiol. 2018, 36, 582–586. [CrossRef]

[19] Sultana, Z.; Guria, S.; Das, M. A Systematic Review at the Crossroads of Polymorphisms in Pro inflammatory Cytokine Genes and Gastric Cancer Risk. J. Atoms Molecules 2014, 4, 791.

[20] Pandey, A.; Tripathi, S.C.; Shukla, S.; Mahata, S.; Vishnoi, K.; Misra, S.P.; Misra, V.; Mitra, S.; Dwivedi, M.; Bharti, A.C. Differentially Localized Survivin and STAT3 as Markers of Gastric Cancer Progression: Association with Helicobacter pylori. Cancer Reports 2018, 1, e1004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21] Tsuchiya, Y.; Mishra, K.; Kapoor, V.K.; Vishwakarma, R.; Behari, A.; Ikoma, T.; Asai, T.; Endoh, K.; Nakamura, K. Plasma Helicobacter pylori Antibody Titers and Helicobacter pylori Infection Positivity Rates in Patients with Gallbladder Cancer or Cholelithiasis: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 1911–1915. [CrossRef]

[22] Narang, M.; Puri, A.S.; Sachdeva, S.; Singh, J.; Kumar, A.; Saran, R.K. Celiac Disease and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children: Is There Any Association? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 1178–1182. [CrossRef]

[23] Dutta, A.K.; Reddy, V.D.; Iyer, V.H.; Unnikrishnan, L.S.; Chacko, A. Exploring Current Status of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Different Age Groups of Patients with Dyspepsia. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 36, 509–513. [CrossRef]

[24] Satpathi, P.; Satpathi, S.; Mohanty, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Behera, P.K.; Maity, A.B. Helicobacter pylori Infection in Dyspeptic Patients in an Industrial Belt of India. Trop. Dr. 2017, 47, 2–6. [CrossRef]

[25] Jeyamani, L.; Jayarajan, J.; Leelakrishnan, V.; Swaminathan, M. CagA and VacA Genes of Helicobacter pylori and Their Clinical Relevance. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2018, 61, 66–69. [CrossRef]

[26] Qadri, Q.; Afroze, D.; Rasool, R.; Gulzar, G.M.; Naqash, S.; Siddiqi, M.A.; Shah, Z.A. CagA Subtyping in Helicobacter pylori Isolates from Gastric Cancer Patients in an Ethnic Kashmiri Population. Microb. Pathog. 2014, 66, 40–43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[27] Pandya, H.B.; Agravat, H.H.; Patel, J.S.; Sodagar, N. Emerging Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of Helicobacter pylori in Central Gujarat. Indian J. Med Microbiol. 2014, 32, 408–413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28] Nisha, K.J.; Nandakumar, K.; Shenoy, K.T.; Janam, P. Periodontal Disease and Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Community-Based Study Using Serology and Rapid Urease Test. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 37–45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[29] Pandey, R.; Misra, V.; Misra, S.P.; Dwivedi, M.; Misra, A. Helicobacter pylori Infection and a P53 Codon 72 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism: A Reason for an Unexplained Asian Enigma. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 9171–9176. [CrossRef]

[30] Fujiya, K.; Nagata, N.; Uchida, T.; Kobayakawa, M.; Asayama, N.; Akiyama, J.; Shimbo, T.; Igari, T.; Banerjee, R.; Reddy, D.N.; et al. Different Gastric Mucosa and CagA Status of Patients in India and Japan Infected with Helicobacter pylori. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014, 59, 631–637. [CrossRef]

[31] Ghosh, P.; Bodhankar, S.L. Association of Smoking, Alcohol and NSAIDs Use with Expression of Cag A and Cag T Genes of Helicobacter pylori in Salivary Samples of Asymptomatic Subjects. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 479–484. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[32] Shukla, S.K.; Prasad, K.N.; Tripathi, A.; Jaiswal, V.; Khatoon, J.; Ghsohal, U.C.; Krishnani, N.; Husain, N. Helicobacter pylori cagL Amino Acid Polymorphisms and Its Association with Gastroduodenal Diseases. Gastric Cancer 2013, 16, 435–439. [CrossRef]

[33] Bansal, V.K.; Misra, M.C.; Chaubal, G.; Gupta, S.D.; Das, B.; Ahuja, V.; Sagar, S. Helicobacter pylori in Gallbladder Mucosa in Patients with Gallbladder Disease. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 31, 57–60. [CrossRef]

[34] Kashyap, B.; Kaur, I.R.; Garg, P.K.; Das, D.; Goel, S. Test and Treat’policy in Dyspepsia: Time for a Reappraisal. Trop. Dr. 2012, 42, 109–111. [CrossRef]

[35] Tripathi, S.; Ghoshal, U.; Mittal, B.; Chourasia, D.; Kumar, S.; Ghoshal, U.C. Association between Gastric Mucosal Glutathione-S-Transferase Activity, Glutathione-S-Transferase Gene Polymorphisms and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Gastric Cancer. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 30, 257–263. [CrossRef]

[36] Shukla, S.K.; Prasad, K.N.; Tripathi, A.; Singh, A.; Saxena, A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Krishnani, N.; Husain, N. Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Load and Its Association with Helicobacter pylori Infection in Gastroduodenal Diseases. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, 583–590. [CrossRef]

[37] Goenka, M.K.; Majumder, S.; Sethy, P.K.; Chakraborty, M. Helicobacter pylori Negative, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drug-Negative Peptic Ulcers in India. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 30, 33–37. [CrossRef]

[38] Shukla, S.K.; Prasad, K.N.; Tripathi, A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Krishnani, N.; Nuzhat, H. Quantitation of Helicobacter pylori ureC Gene and Its Comparison with Different Diagnostic Techniques and Gastric Histopathology. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 86, 231–237. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[39] Mishra, R.R.; Tewari, M.; Shukla, H.S. Helicobacter pylori and Pathogenesis of Gallbladder Cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 26, 260–266. [CrossRef]

[40] Nath, G.; Singh, V.; Mishra, S.; Maurya, P.; Rao, G.; Jain, A.K.; Dixit, V.K.; Gulati, A.K. Drug Resistance Pattern and Clonality in H. pylori Strains. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2009, 3, 130–136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[41] Prasad, K.N.; Saxena, A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Bhagat, M.R.; Krishnani, N. Analysis of Pro12Ala PPAR Gamma Polymorphism and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Peptic Ulcer Disease. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1299–1303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42] Chakravorty, M.; De Datta, D.; Choudhury, A.; Santra, A.; Roychoudhury, S. Association of Specific Haplotype of TNFα with Helicobacter pylori-Mediated Duodenal Ulcer in Eastern Indian Population. J. Genetics 2008, 87, 299–304. [CrossRef]

[43] Nath, G.; Mishra, S.; Singh, V.; Rao, G.; Jain, A.K.; Dixit, V.K.; Gulati, A.K. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in Stool Specimens: Comparative Evaluation of Nested PCR and Antigen Detection. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2008, 2, 206–210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[44] Saxena, A.; Prasad, K.N.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Bhagat, M.R.; Krishnani, N.; Husain, N. Polymorphism of-765G> C COX-2 Is a Risk Factor for Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Peptic Ulcer Disease in Addition to H. pylori Infection: A Study from Northern India. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2008, 14, 1498. [CrossRef]

[45] Mishra, S.; Singh, V.; Rao, G.R.K.; Dixit, V.K.; Gulati, A.K.; Nath, G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Asymptomatic Subjects—A Nested PCR Based Study. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2008, 8, 815–819. [CrossRef]

[46] Sharma, P.K.; Suri, T.M.; Venigalla, P.M.; Garg, S.K.; Mohammad, G.; Das, P.; Sood, S.; Saraya, A.; Ahuja, V.; Tm, S.; et al. Atrophic Gastritis with High Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Is a Predominant Feature in Patients with Dyspepsia in a High Altitude Area. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2014, 35, 246–251. [CrossRef]

[47] Yadav, M.; Rishi, J.; Nijawan, S. Chronic Urticaria and Helicobacter pylori. Indian J. Med Sci. 2008, 62, 157–162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[48] Tiwari, S.K.; Manoj, G.; Kumar, G.V.; Sivaram, G.; Hassan, S.I.; Prabhakar, B.; Devi, U.; Jalaluddin, S.; Kumar, K.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Genotyping Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients in Younger Age Groups with Gastric Cancer. Postgrad. Med J. 2008, 84, 193–197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[49] Arachchi, H.S.J.; Kalra, V.; Lal, B.; Bhatia, V.; Baba, C.S.; Chakravarthy, S.; Rohatgi, S.; Sarma, P.M.; Mishra, V.; Das, B.; et al. Prevalence of Duodenal Ulcer-Promoting Gene (dupA) of Helicobacter pylori in Patients with Duodenal Ulcer in North Indian Population. Helicobacter 2007, 12, 591–597. [CrossRef]

[50] Ahmed, K.S.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, I.; Tiwari, S.K.; Habeeb, A.; Ahi, J.D.; Abid, Z.; Ahmed, N.; Habibullah, C.M. Impact of Household Hygiene and Water Source on the Prevalence and Transmission of Helicobacter pylori: A South Indian Perspective. Singapore Méd. J. 2007, 48, 543–549. [PubMed]

[51] Ahmed, K.S.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, I.; Tiwari, S.K.; Habeeb, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Ahi, J.D.; Abid, Z.; Alvi, A.; Hussain, M.A.; et al. Prevalence Study to Elucidate the Transmission Pathways of Helicobacter pylori at Oral and Gastroduodenal Sites of a South Indian Population. Singapore Méd. J. 2006, 47, 291–296. [PubMed]

[52] Biswal, N.; Ananathakrishnan, N.; Kate, V.; Srinivasan, S.; Nalini, P.; Mathai, B. Helicobacter pylori and Recurrent Pain Abdomen. Indian J. Pediatr. 2005, 72, 561–565. [CrossRef]

[53] Tiwari, S.K.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, K.S.; Ali, S.M.; Ahmed, I.; Habeeb, A.; Kauser, F.; Hussain, M.A.; Ahmed, N.; Habibullah, C.M. Polymerase Chain Reaction Based Analysis of the Cytotoxin Associated Gene Pathogenicity Island of Helicobacter pylori from Saliva: An Approach for Rapid Molecular Genotyping in Relation to Disease Status. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 20, 1560–1566. [CrossRef]

[54] Singh, M.; Prasad, K.N.; Yachha, S.K.; Saxena, A.; Krishnani, N. Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children: Prevalence, Diagnosis and Treatment Outcome. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 100, 227–233. [CrossRef]

[55] Anand, P.S.; Nandakumar, K.; Shenoy, K.T. Are Dental Plaque, Poor Oral Hygiene, and Periodontal Disease Associated with Helicobacter pylori Infection? J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 692–698. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[56] Tovey, F.I.; Hobsley, M.; Kaushik, S.P.; Pandey, R.; Kurian, G.; Singh, K.; Sood, A.; Jehangir, E. Duodenal Gastric Metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori Infection in High and Low Duodenal Ulcer-Prevalent Areas in India. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 19, 497–505. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[57] Shaikh, S.; Khaled, M.A.; Islam, D.A.; Kurpad, A.V.; Mahalanabis, D. Evaluation of Stool Antigen Test for Helicobacter pylori Infection in Asymptomatic Children from a Developing Country Using 13C-Urea Breath Test as a Standard. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2005, 40, 552–554. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[58] Batmanabane, V.; Kate, V.; Ananthakrishnan, N. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Patients with Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy––A Study from South India. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004, 10, 136.

[59] Shankar, R.R.; Vikram, K.; Ananthakrishnan, N.; Harish, B.N.; Jayanthi, S. Erosive Gastroduodenitis and Helicobacter pylori Infection. Signature 2003, 9, 276. [PubMed]

[60] Singh, V.; Trikha, B.; Nain, C.K.; Singh, K.; Vaiphei, K. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer in India. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002, 17, 659–665. [CrossRef]

[61] Venkatesan, A.; Gonuguntla, A.; Abraham, A.P.; Janumpalli, K.K.R.; Lakshminarayana, B. Leveraging the Multidimensional Poverty Index to estimate Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Districts in Karnataka, India. Trop. Dr. 2024, 54, 16–22. [CrossRef]

[62] Datta, S.; Khyriem, A.B.; Lynrah, K.G.; Marbaniang, E.; Topno, N. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori in patients evaluated for dyspeptic symptoms in North-Eastern India with focus on detection of clarithromycin resistance conferring point mutations A2143G and A2142G within bacterial 23S rRNA gene. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 100652. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

[63] Sruthi, M.A.; Mani, G.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Selvaraj, J. Dental Caries as a Source of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children: An RT-PCR Study. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 33, 82–88. [CrossRef]

[64] Poddar, U. Helicobacter pylori: A Perspective in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Paediatrics Int. Child Health 2019, 39, 13–17. [CrossRef]

[65] Kuo, Y.T.; Liou, J.M.; El-Omar, E.M.; Wu, J.Y.; Leow, A.H.R.; Goh, K.L.; Das, R.; Lu, H.; Lin, J.T.; Tu, Y.K.; et al. Primary Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori in the Asia-Pacific Region: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 707–715. [CrossRef]

[66] Mhaskar, R.S.; Ricardo, I.; Azliyati, A.; Laxminarayan, R.; Amol, B.; Santosh, W.; Boo, K. Assessment of Risk Factors of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Peptic Ulcer Disease. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2013, 5, 60–67. [CrossRef]

[67] Graham, D.Y.; Adam, E.; Reddy, G.T.; et al. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori Infection in India: Comparison of Developing and Developed Countries. Dig Dis Sci. 1991, 38, 1084–1088. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[68] Gill, H.H.; Majmudar, P.; Shankaran, K.; Desai, H.G. Age-Related Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Antibodies in Indian Subjects. Indian J Gastroenterol 1994, 13, 92–94. [PubMed]

[69] Poddar, U.; Yachha, S.K. Helicobacter pylori in Children: An Indian Perspective. Indian Pediatrics 2007, 44, 761–770. [PubMed]

[70] Bhan, M.K.; Bahl, R.; Sazawal, S.; Sinha, A.; Kumar, R.; Mahalanabis, D.; Clemens, J.D. Association between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Increased Risk of Typhoid Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 186, 1857–1860. [CrossRef]

[71] Romshoo, G.J.; Malik, G.M.; Basu, J.A.; Bhat, M.Y.; Khan, A.R. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Peptic ulcer Patients of Highly Endemic Kashmir Valley. Diagn. Ther. Endosc. 1999, 6, 31–36. [CrossRef]

[72] Adlekha, S.; Chadha, T.; Krishnan, P.; Sumangala, B. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection among Patients Undergoing upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in a Medical College Hospital in Kerala, India. Ann. Med Health Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 559–563. [CrossRef]

[73] Thyagarajan, S.P.; Ray, P.; Das, B.K.; Ayyagari, A.; Khan, A.A.; Dharmalingam, S.; Rao, U.A.; Rajasambandam, P.; Ramathilagam, B.; Bhasin, D.; et al. Geographical Difference in Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of Helicobacter pylori Clinical Isolates from Indian Patients: Multicentric Study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 18, 1373–1378. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher or editors. The publisher and editors assume no responsibility for any injury or damage resulting from the use of information contained herein.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more