APA Style

Avanish Kumar, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. (2025). Sustainable Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using Various Treatment Processes: A Review. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0018). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.111130MLA Style

Avanish Kumar, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. "Sustainable Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using Various Treatment Processes: A Review". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0018, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.111130.Chicago Style

Avanish Kumar, Girdhari Lal Devnani, Dan Bahadur Pal. 2025. "Sustainable Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using Various Treatment Processes: A Review." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0018. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.111130.

ACCESS

Review Article

ACCESS

Review Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0018

Avanish Kumar

akumarch@hbtu.ac.in

Girdhari Lal Devnani

gldevnani@hbtu.ac.in

Dan Bahadur Pal

dbpal@hbtu.ac.in

Department of Chemical Engineering, Harcourt Butler Technical University, Kanpur 208002, Uttar Pradesh, India

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 27 May 2025 Accepted: 27 Oct 2025 Available Online: 29 Oct 2025 Published: 06 Nov 2025

Organic pollutants, such as dyes and colorants, are water-soluble compounds produced by various industries, including textiles, food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, printing, paints, leather, and plastics. Dyes are of particular concern because their stable aromatic structures make them toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic to living organisms. Therefore, environmental scientists have focused on developing various physical, chemical, and biological treatment processes to remove these contaminants from wastewater. The conventional techniques, such as coagulation, flocculation, precipitation, photocatalytic degradation, ion exchange, and membrane filtration, have been widely adopted. More recently, biomass-based waste materials such as bagasse, green algal biomass, and household vegetable and agricultural residues have been investigated as promising, low-cost, and sustainable adsorbents for dye removal. In addition, nanomaterials such as zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, silica powder, carbon nanotubes, and well-structured biocomposite materials have also shown great potential in wastewater treatment. This review examines major treatment technologies and highlights their merits and limitations, supported by comparative tables and illustrative figures.

Sustainable degradation of dyes using various treatment processes Degradation of organic pollutants from textiles, food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, etc. Removal of using various physical, chemical, and biological treatment processes. Conventional treatment techniques include coagulation, flocculation, degradation, ion exchange, and membrane filtration

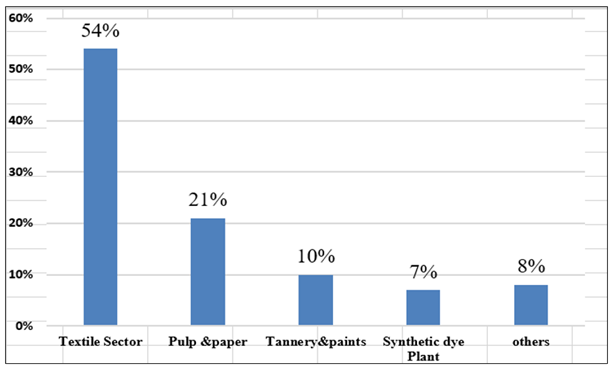

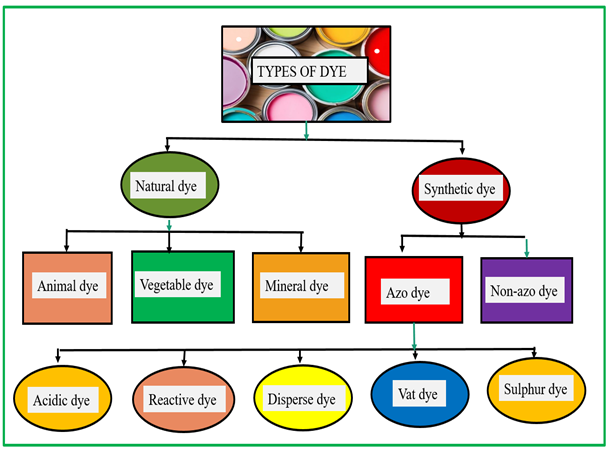

A dye is a colored substance, soluble in water or other solvents, that forms chemical bonds with textiles, paper, or leather to impart color to these materials [1]. Dyes are mainly divided in natural dyes and synthetic dyes. Most of the natural dyes are derived from natural resources like flowers, bark, plants, animals, and minerals. Natural dyes are generally biodegradable and typically offer a narrower color range and lower durability. In contrast, synthetic dyes are chemically produced from petrochemicals and coal tar derivatives, which offer a wider color range and higher durability [2]. Synthetic dyes are a relatively recent discovery, and their large-scale production commenced in response to the growing demand for dyes [3]. In 1856, WH Perkin made a groundbreaking contribution by inventing a wide range of synthetic dyes, offering vibrant and colorfast shades for various applications [4]. While this invention resolved the limitations associated with natural dyes, new challenges emerged as industries using these synthetics started to discharge into the open environment without performing waste dye treatment. Approximately 700,000 tons of various coloring agents, derived from around 100,000 commercially available dyes, are produced annually. However, untreated dye effluents are frequently discharged into rivers, ponds, and lakes. Globally, the textile sector accounts for the largest share of wastewater discharge (54%), followed by the pulp and paper industry (21%), paint and tannery industries (10%), and synthetic dye plants (7%) [5]. The remaining ~8% arises from other sectors, which also contribute to dye-effluent generation through their respective processes. Figure 1 shows the demographic representation of different industrial contributions to dye effluents. The extensive use of dyestuffs in various textile processes results in the generation of large volumes of dye-contaminated wastewater [6]. Since the textile industry consumes various kinds of dyes and chemicals, which involve significant amounts of water in different unit operations, more than 75% of residual dye mixtures are discharged untreated into rivers, severely affecting aquatic organisms [7]. A range of dye-removal methods has been documented, with varying performance and drawbacks. However, although a variety of viable technologies exist, not all of them prove effective or practical due to inherent limitations. Figure 2 presents a schematic representation of different types of dye effluents obtained from various industrial sources. The emphasis must be on eliminating contaminants from wastewater without producing additional hazardous by-products [8]. Synthetic dyes have become essential components, widely used to impart color to textiles, cosmetics, plastics, and printing materials [9]. This widespread application is primarily due to their inherent resistance to degradation, as their complex and stable molecular structures contain auxochromes (water-soluble bonding groups) and chromospheres (color-imparting groups) [10]. This structural complexity complicates the degradation of dyes through conventional treatment methods. To ensure that dyed materials retain their color and do not fade easily, even under extreme heat, exposure to oxidizing agents, or intense light, dyes are deliberately designed for high stability [11]. However, the dye effluents as industrial waste transform clean water into contaminated water in the river. This dye reduces the dissolved oxygen (DO) levels, which in turn increases the biological oxygen demand (BOD) and causes odor formation, thereby adversely affecting nearby aquatic ecosystems and human populations [12]. Since most of the village population or poor communities live near riverbanks, there is a risk of becoming sick from unknowingly consuming contaminated water [13]. The gradual degradation of the environment negatively affects human health, leading to conditions such as skin disorders, respiratory difficulties, nausea, and vomiting [14]. These water contamination issues have gained attention over the past 30 years as health problems have become more apparent. Subsequently, efforts were made to gather information on dyes, their applications, and methods to remove them [15]. A recent review analyzed publication trends in water-treatment technologies from 2015 to 2024. Figure 3a illustrates the absolute number of published papers, indicating that adsorption remains the most researched technique, with the number of publications steadily increasing from approximately 120 in 2015 to over 260 in 2024. Reverse osmosis and membrane filtration also show consistent growth, followed closely by coagulation & flocculation, and a notable rise in ultra- and nano-membranes, especially after 2020 [16]. Ion exchange maintains a moderate presence, while irradiation consistently has the fewest publications. Figure 3b illustrates the percentage share of publications per technology over time, showing that although adsorption dominates in absolute numbers, its percentage share is slowly declining due to the increasing contribution of other technologies [17]. Notably, ultra- and nano-membranes show a significant upward trend in percentage share, reflecting growing research interest. Meanwhile, reverse osmosis, coagulation & flocculation, and ion exchange show a steady to slight decline in percentage contribution over the years [18]. This review evaluates physical, chemical, and biological treatment methods, including coagulation, flocculation, precipitation, ion exchange, membrane filtration, and photocatalytic degradation [19]. In addition, it seeks to explore the potential of emerging low-cost and eco-friendly materials, including biomass-based waste like bagasse, green algal biomass, and agricultural residues, as well as advanced materials like carbon nanotubes, zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, silica powder, and engineered biocomposites for improving the efficiency and sustainability of dye removal from wastewater [20]. 1.1. Various Dyes and Their Applications Synthetic dyes can be classified based on their molecular structure, application, or solubility. Soluble dyes include categories like acid, basic, direct, mordant, and reactive dyes, while insoluble dyes encompass azo, disperse, sulfur, and vat dyes [21]. Among these, azo dyes stand out as the most widely produced type, accounting for 70% of the total production and being extensively applicable worldwide [22]. Despite their structural diversity, all synthetic dyes share a common drawback due to their hazardous nature. Figure 4 shows the various types of dyes used in different applications. So, it is necessary that untreated water should not be discharged into the atmosphere where it can contaminate water sources due to its toxicity [23]. Some names of essential types of dye, like reactive dyes, are water-soluble colorants that form covalent bonds with hydroxyl groups in cellulose or amino groups in proteins, giving them high wash fastness and bright shades. They are extensively applied to printing inks, silk, wool, cellulosic fibers, and cotton [24]. Solvent dyes, such as Solvent Red 26 and Solvent Blue 35, are non-polar and water-insoluble, which allows them to dissolve in organic solvents. This makes them particularly suitable for coloring lubricants, oils, waxes, plastics, and varnishes, where good solubility and transparency are required. Sulfur dyes, with Sulfur Black being the most common, are applied to rayon, silk, wood, leather, paper, and polyamide fibers [25]. These dyes are typically insoluble in water and must first be reduced in an alkaline solution of sodium sulfide to a soluble form. Afterward, they penetrate the fiber and are re-oxidized to their original insoluble form, producing excellent wash durability. Vat dyes, such as Vat Blue 4 (indanthrene), rely on a reduction–oxidation process: they are first reduced to a soluble leuco form, which allows them to penetrate fibers such as cotton, cellulosic fibers, rayon, polyester–cotton blends, and wool, before being oxidized back to their insoluble state within the fabric. Azo dyes, characterized by their –N=N– azo linkage, are widely used due to their versatility and bright color range, including bluish-red shades. They are applied to cotton, rayon, polyester, cellulose, and acetate, and their chromophore–auxochrome system provides good strength [26].

![Figure 3: (a) Bibliography of publications (technology-wise) (b) the percentage share of publications based on dye removal [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].](/uploads/source/articles/sustainable-processes-connect/2025/volume1/20250018/image003.png)

Historically, dye removal relied on primary treatments such as equalization and sedimentation, partly because specific discharge limits for dyes were absent. However, these primary methods are insufficient to meet permissible limits, are not cost-effective due to higher maintenance and operating costs, and can generate secondary pollutants [27]. Currently, extensive research is being conducted to identify the ideal dye removal method that would allow for the recovery and reuse of dye wastewater [28]. In modern times, or currently, the water treatment of dye-removal treatments is generally categorized as physical, chemical, or biological. Although numerous dye removal technologies have been developed, only a select few are useful in industrial systems due to the limitations associated with most of these methods [29]. The schematic diagram for different dye removal methods is shown in Figure 5. 2.1. Physical Treatment of Dye Physical treatment techniques such as coagulation, flocculation, ion exchange, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis membrane filtration are important water treatment technologies based on mechanical and mass transfer processes [30]. Among the various approaches, including physical, chemical, and biological methods, physical techniques are preferred at the initial stage of dye removal due to their high efficiency [12]. Here, the summary of various physical methods with their respective advantages and disadvantages [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] is given in Table 1 as follows. Different physical dye removal methods. 2.2. Chemical Methods for Dye Removal The chemical approach involves the application of chemical principles to extract dyes from waste for use in various separation techniques. The treatment methods encompass oxidation, electrochemical destruction, photochemical or ultraviolet irradiation, Fenton oxidation, ion exchange, and ozonation processes. A comparative summary of their descriptions, advantages, and disadvantages is provided in Table 2, based on references. Chemical treatment method along with its advantages & disadvantages. 2.3. Biological Methods for Dye Removal & Their Efficiency Biological methods include aerobic and anaerobic processes to use dye effluents before their discharge into the environment. The conventional approach is predominantly favored due to its efficacy, which ranges from 85% to 98% [48]. Among these techniques, adsorption stands out as the most effective method for degrading a broad spectrum of dyes, either individually or as mixtures. Typically, the adsorption and enzyme degradation methods can be employed iteratively until the adsorbent reaches its saturation point [49]. The only drawback to this approach is the potentially higher cost associated with specific adsorbents, which can be mitigated by exploring cost-effective raw materials to create alternative adsorbents. Given the effectiveness of both enzyme degradation and adsorption techniques in dye removal, there is a compelling case for investigating the integration of these methods into a unified, comprehensive technology for future dye removal applications. In the same way, a comparative analysis among Enzyme vs. Microbial vs. Algal Approaches is also presented as Table 3 [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]: Comparative analysis: enzyme vs. microbial vs. algal approaches.

Method

Description

Advantages

Disadvantages

1. Adsorption

Adsorption is a mass transfer process that involves the use of adsorbents with high capacity that accumulate dye molecules on active surfaces [31]

It is excellent for removing a variety of dyes, and adsorbents can be reused or regenerated.

It can be expensive.

2. Coagulation and Flocculation

In this process, some coagulants and flocculants are used to settle down the aggregate of the dye molecules. After this operation, filtration is applied to remove the dye molecules and water [32]

It is cost-effective and suitable for dispersant, sulfur, and vat dye effluents.

Generates significant concentrated sludge.

3. Ion Exchange

This treatment method removes ionic contaminants, such as dye molecules, from water [33]

It is regenerable and effective for dye removal, producing high-quality water.

Limited effectiveness for certain dyes.

4. Irradiation

Uses radiation to eliminate molecules of dye from wastewater.

Effective at the laboratory scale, but requires substantial dissolved oxygen.

Irradiation is Expensive, not suitable for dye removal, prone to fouling, and results in concentrated sludge [34].

5. Membrane Filtration

It is a thin membrane that is applied to separate dye and water molecules [35]

Membrane Filtration is considered best for water recovery and reuse.

Initial investment can be costly, and membranes are prone to fouling.

6. Ultra And Nano Membrane Process

wastewater of dye effluent is passed through a thin-size membrane [36]

It is Capable of removing any dye type.

Ultra and Nano Membrane Process is also high cost, high energy consumption, and needs backwashing [37]

7. Reverse Osmosis

Reverse Osmosis utilizes pressure to pass water through a fragile membrane, allowing osmosis to remove contaminants and produce pure water [38]

Widely applied for water recycling, effective in decolorizing and desalting various dyes, yielding pure water.

Costly and necessitates high pressure

Method

Description

Advantages

Disadvantages

Advanced Oxidation Process

(AOPs) refers to a set of chemical treatment methods that generate highly reactive species, particularly hydroxyl radicals (•OH), to degrade and mineralize organic pollutants, including dyes, in wastewater. AOP processes are highly effective for breaking down complex dye molecules that are resistant to conventional treatment methods [39]

Effective for toxic materials. Suitable for unusual conditions.

The Advanced Oxidation Process is Expensive. Inflexible. Produces undesirable by-products. PH-dependent. High electricity cost. Less effective at high flow rates [40]

Electrochemical Destruction

Electrochemical methods are attractive for dye removal due to their high efficiency, ability to operate without chemical additives, and potential for complete mineralization of dyes without secondary sludge formation. However, electrochemical methods face challenges related to high energy consumption and electrode material degradation, which need to be optimized [41]

Electrochemical Destruction does not consume. No sludge buildup. Suitable for soluble and insoluble dyes [42]

A greater production of potentially hazardous substances. High cost of electricity. Less successful at high flow rates

Fenton reaction

The Fenton reaction involves a reaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and ferrous iron (Fe2+) in the presence of acidic conditions (typically using sulfuric acid, H2SO4) [43]

It is suitable for both soluble and insoluble dyes, effectively eliminating harmful pollutants. This method is typically well-suited for wastewater with a high solid content [44]

This process is ineffective for eliminating disperse and vat dyes and tends to produce a substantial amount of iron sludge. Furthermore, it is noted for its delayed reaction and operates most efficiently under acidic conditions (low pH) [45]

Ozonation

Utilizes ozone from oxygen to eliminate dye particles.

Effective for color removal and disinfection. Not generate chemical residuals.

High equipment and energy costs. It may not remove all dyes.

Photochemical Reaction

Photochemical reactions can involve the breaking or formation of chemical bonds, resulting in the creation of new substances or the alteration of existing molecules [46]

It is effective for color and organic matter removal. It can treat a wide range of dyes [47]

Hydrogen peroxide cost. Sludge generation

Parameter

Enzyme-Based Approach

Microbial Approach

Algal Approach

Ref.

Mechanism

Direct oxidation or breakdown of dyes via enzymes

Biodegradation or biosorption using bacteria/fungi

Bio sorption + biodegradation using algae

[50]

Common Agents/Species

Laccase, peroxidase, manganese peroxidase

Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Phanerochaete, Aspergillus

Chlorella vulgaris, Spirulina,

[51]

Typical Removal Efficiency

70–95%

50–90%

40–80%

[52]

Reaction Time

Minutes to hours

Hours to days

Several days

[53]

Operational Conditions

Optimal pH, temperature, and enzyme stability are needed

Tolerates moderate variation in pH and temperature

Requires light, CO2, and stable pH

[54]

Sludge Generation

Minimal

Moderate

Low

[55]

Advantages

Fast, highly specific, no microbial growth required

Inexpensive, adaptable to multiple dyes

Eco-friendly, biomass reuse possible

[56]

Limitations

High enzyme cost, sensitive to inhibitors

Sensitive to toxicity, slow degradation for complex dyes

Slower rate, needs sunlight and CO2, lower tolerance to toxicity

[57]

Byproduct Toxicity

Often non-toxic

Possibly toxic intermediates

Usually, non-toxic

[58]

Scalability

Challenging (due to the cost of enzymes)

Highly scalable in bioreactors

Scalable in ponds or photo bioreactors

[59]

Environmental Impact

Low (enzyme residues are biodegradable)

Low–moderate (depends on sludge disposal)

Very low (uses renewable light

and CO2)[60]

Energy Demand

Low–Medium (if immobilized or reused)

Low

Low

[61]

Reuse/Recovery

Possible via immobilization

Difficult

Biomass can be harvested and reused

[62]

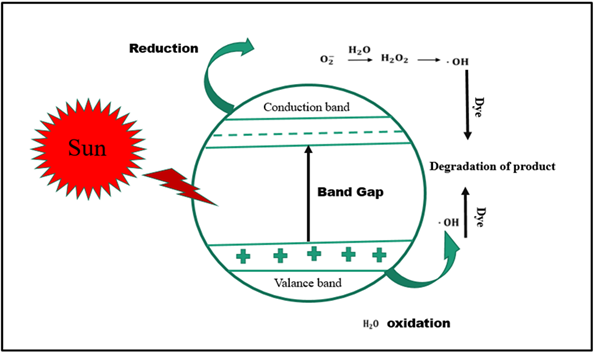

Several methods have been thoroughly tested, but treatment through adsorption is one of the best techniques for dye removal due to having excellent capacity to eliminate different types of dye [63]. It is widely recognized that conventional methods are inefficient in eliminating synthetic dyes from dye wastewater, making adsorption one of the most suitable approaches for dye removal [64]. Dye effluents treated using the adsorption method have consistently yielded higher water quality compared to other dye removal techniques [65]. The one drawback associated with this method is the high cost of adsorbents. However, the discovery of cost-effective yet equally efficient adsorbents has transformed this approach into an economically viable method for dye removal on a global scale. Adsorption is a mass transfer process in which adsorbate accumulates at the surface of adsorbents. The adsorption process is driven by various forces, including physical interactions, electrostatic forces, and chemical bonding, resulting in the concentration of solutes on the solid surface [66]. The existing advanced technology for the removal of dye may be explained as follows: 3.1. Mechanism of Natural Adsorbent Adsorption is a process in which substances are captured or accumulated at the interface of two phases, typically a solid surface and a fluid, such as a liquid or gaseous solution obtained from the environment [67]. This phenomenon effectively reduces the concentration of dissolved dye particles present in dye-containing wastewater. The term adsorbate refers to the material that is adsorbed, while the substance used to carry out the adsorption process is known as the adsorbent. Adsorption can occur through either physical or chemical mechanisms. Among these, physical adsorption is more commonly employed, whereas chemisorption is utilized in specific applications [68]. In physisorption, various weak forces such as van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, and polar interactions are involved. Adsorption is considered a highly effective method for dye removal due to its low dependence on specialized treatment systems and its relatively simple operation. Van der Waals forces are weak, non-specific interactions that occur between all atoms or molecules, including London dispersion forces, Debye forces, and Keesom forces. These forces play a crucial role in physisorption, particularly in dye adsorption on nonpolar surfaces, such as activated carbon or untreated biomass [69]. They enable reversible dye attachment without strong chemical bonding. While π–π interactions, on the other hand, involve non-covalent stacking between aromatic rings in both dyes and adsorbents. These are stronger and more specific, enhancing dye removal when adsorbents like biochar have graphitic or aromatic structures, making them particularly effective for aromatic dyes like methylene blue and Congo red. Additionally, no pre-treatment is necessary to initiate the adsorption process. Sometimes, adsorption is used in conventional methods to decolorize dye effluents; the effectiveness of the adsorption is enhanced when a suitable adsorbent is used, ensuring efficient dye removal [70]. Another desirable feature of adsorption is that it does not produce additional hazardous materials during operation. Figure 6 shows the various adsorbents, while an essential overview of Adsorption Kinetics, Reactor Design, and Toxicological Assessment is given as follows in Table 4. Overview of adsorption kinetics, reactor design, and toxicological assessment. 3.1.1. Different Adsorbents Used for Dye Removal All adsorbents are porous materials capable of trapping adsorbate on their surface. Adsorbents can be made from a variety of raw materials, not limited to solid substances, and can even include enzymes. The cost of the adsorbent is a common concern associated with the adsorption technique. To address this issue, researchers have identified and developed cost-effective adsorbents, drawing on research from various sources to demonstrate the existence of inexpensive yet effective adsorbents [71]. The key characteristics of a good adsorbent include its good adsorption capacity to trap solute molecules, high surface area (higher porosity results in greater surface area and higher adsorption capacity), short adsorption time (rapid equilibrium reaching), and versatility to remove molecules of different sizes (ability to function under varying dye concentrations), pH levels, and temperatures. 3.1.2. Factors Influencing Adsorption The rate of adsorption is influenced by several key parameters related to the adsorption process. Any changes in these five parameters can impact the adsorption rate. To achieve the desirable removal rate, it’s essential to establish optimal adsorption conditions, which outlines the five most significant parameters presented as: Adsorbent Dosage: It measures the quantity of adsorbent containing an active site to adsorbate, which depends on dye concentration and pH of dye solution [65]. Contact Time: It measures the duration of contact between the adsorbate and adsorbent. As the contact period between the active site and the adsorbate is increased, the chances of adsorption are enhanced [72]. Dye Concentration: it also affects the adsorption process of available binding sites and the adsorbent's surface. Whenever dye concentration is increased, then the number of available active sites is reduced, causing a decrease in the efficiency of dye removal [65]. pH: It indicates the solution’s acidity or alkalinity. Adsorption rates can be influenced by pH, which determines the electrostatic interactions between charged dye molecules. Temperature: Adsorption is significantly influenced by the solution’s temperature processes based on the dye effluent’s features. For an endothermic reaction, high temperature is suited for the adsorption of dye, while for an exothermic reaction, low temperature is suited for the adsorption of dye [73]. 3.2. Photocatalytic Processes Photo oxidation utilizes light, typically in the form of ultraviolet or sunlight, and a catalyst to produce highly reactive species, such as hydroxyl radicals (OH), which break down and mineralize organic pollutants, including dyes [74]. When the catalyst is exposed to UV light, it becomes excited, generating electron-hole pairs. These electron-hole pairs react with water and oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species, primarily hydroxyl radicals. These radicals then attack and degrade the dye molecules, breaking them down into smaller and less harmful compounds [75]. Photo oxidation is effective against a wide range of organic dyes. For example, the methylene blue was removed by photochemical decomposition using a combined system. To further enhance color removal in this process, titanium dioxide was immobilized with polyvinyl alcohol [76]. The starting concentration of dye of 20 mg/L, the UV light intensity of 4 W, the liquid volumetric flow rate of 2 mL/min, and the wavelength of 254 nm were found to be the ideal process parameters. Contact time is less than 20 h, which is needed for the maximum dye removal reaction time—90% Maximum Efficiency, [77]. The principle of the Mechanism of Photocatalytic Dye Degradation is illustrated in Figure 7 as follows. 3.3. Ozonation The ozonation process uses ozone (O3), a powerful oxidizing agent, to treat wastewater. Ozone is bubbled through the water, and it reacts with organic pollutants, including dyes, leading to their degradation [78]. Ozone reacts with the double bonds and aromatic rings present in dye molecules. Photo oxidation reaction involves the transfer of oxygen atoms, leading to the cleavage of chemical bonds within the dye molecules [79]. Ozonation breaks down the dye into simpler, less harmful compounds. Ozonation is effective against a wide variety of dyes, including those resistant to biological treatments [80]. It’s also valuable for decolorizing and dropping the COD of industrial wastewater. It’s a potent and fast-acting oxidizing agent, capable of degrading a wide range of pollutants. The ozonation method was carried out in a batch reactor. The optimal conditions for processing were a pH of 9, a 6-h reaction duration, and a constant temperature of 35 °C [81]. The research findings revealed that a reaction time of one-fourth of an hour, a dye concentration of 50 mg/dm3, an ozone dosage of 300 mg/dm3, and an acidic pH were the optimal conditions for dye removal. Specifically, Acid Red 183 can be eliminated with noteworthy efficiency, up to 97%, through the ozonation method. To optimize the traditional method of ozonation for removing dyes, a composite design featuring a central core was implemented [82]. 3.4. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Using LED-Based Light Sources Photo-catalytic degradation of dyes using LED-based light sources, which is based on the activation of semiconductor photo-catalysts (like TiO2 or ZnO) by LED light of suitable wavelength, generating electron-hole pairs. These charge carriers produce reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl (•OH) and superoxide radicals (•O2−), which attack and break down dye molecules into harmless end products like CO2, H2O, and inorganic ions. LEDs offer several advantages over traditional UV lamps, including lower energy consumption, wavelength tenability, longer lifespan, and minimal heat generation [83]. This makes LED-driven photo-catalysis an efficient, eco-friendly, and emerging technology for wastewater treatment, as demonstrated in recent studies [84]. The mechanism of dye degradation using LED-activated photocatalysis begins with the absorption of photons by a semiconductor photocatalyst, where LED light of suitable wavelength excites electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), generating electron-hole pairs. These charge carriers drive redox reactions: electrons reduce oxygen molecules on the catalyst surface to form superoxide radicals (•O2−), while holes oxidize water or hydroxide ions to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [85]. These reactive oxygen species subsequently attack the dye molecules, breaking down their complex chromophoric structures into smaller intermediates and ultimately mineralizing them into CO₂, H₂O, and inorganic ions. This makes the process highly efficient for the treatment of dye-contaminated wastewater [86]. 3.5. Ultraviolet (UV) Irradiation This method uses ultraviolet light, typically in the UV-C range (200–280 nm), to disinfect and degrade organic compounds, including dyes, by disrupting their chemical structure. UV light at specific wavelengths directly interacts with the chemical bonds in the dye molecules, breaking them [77]. This leads to the degradation of the dye into smaller fragments, which are often less colored and toxic. UV irradiation is effective against various dyes, especially those that absorb UV light within the appropriate wavelength range [77]. It is commonly used for disinfection and is helpful for breaking down dyes into less harmful substances. The process operates without the use of chemicals, leaves no toxic residues, and efficiently inactivates microorganisms in water, thereby functioning as a dual-purpose technique for wastewater purification. The experimental polysulfonate ultrafiltration membrane underwent minor modifications by incorporating acrylic acid onto its surface. In this study, optimal operating conditions include an irradiation time exceeding 30 min and a pressure of approximately 4 bars [87]. Lower-molecular-weight dyes are more likely to be entirely removed by this process. For instance, dyes such as Acid Green 20 and Acid Blue 92 can be effectively eliminated through UV irradiation, achieving a remarkable maximum removal efficiency of up to 99.9% [88]. The experiment involving pulsed discharge plasma for water treatment demonstrated that the discharge operated in the spark-streamer mixed mode yielded the highest rate of dye removal. For optimal performance, the process should be conducted at a wavelength exceeding 300 nm, under acidic conditions (pH ≈ 3.5), with a dye concentration of 0.01 g/L and a reaction time of more than 100 min. Of particular note, Ultraviolet (UV) Irradiation can successfully remove Methyl Orange, Rhodamine B, and Chicago Sky Blue, with a maximum efficiency of 95% [89]. 3.6. Combined Application of Different Adsorbents for Dye Removal Recent studies indicate that the combined application of adsorbents increase the effectiveness of dye removal. The studies suggest that blending traditional physical adsorbents with biocatalysts, specifically biological adsorbents, can yield remarkable outcomes in dye removal. There is also the proposition that activated carbon, known for its highly efficient dye adsorption properties, could potentially achieve even greater results when combined with equally effective enzymes [90]. Furthermore, combining adsorbents may prove effective not only in removing dyes but also in simultaneously tackling various hazardous substances. If these combined adsorbents synergize effectively, their efficiency in dye removal could surpass current records. Additionally, the use of combined adsorbents tends to expedite the dye removal process [91]. Moreover, it is believed that this combined application of different adsorbents could lead to improvements such as prolonged retention times and reduced overall costs, mainly due to the reuse capability of such a type of combined adsorbent [92]. In contrast, the development of adsorbents generally results in single-use materials, thereby increasing overall production costs.

Aspect

Model/Type

Key Features/Assumptions

Application/Relevance

Kinetic Models

Langmuir isotherm

Monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface; finite number of identical sites.

Used to determine the maximum adsorption capacity and the favorability of the process.

Kinetic Models

Freundlich isotherm

Empirical model; adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces; multilayer possible.

Suitable for systems with diverse active sites; good for low concentration ranges.

Kinetic Models

Pseudo-first-order (PFO)

Adsorption rate is proportional to the number of unoccupied sites; this relationship often fits early-time data.

Describes physical adsorption or initial stage kinetics.

Kinetic Models

Pseudo-second-order (PSO)

The adsorption rate depends on the square of the unoccupied sites; this is a chemisorption mechanism.

Commonly used for dye and heavy metal adsorption with a better overall fit.

Reactor Design

Batch reactors

Simple setup, closed system; easy to control pH, dosage, temperature.

Laboratory studies, small-scale wastewater treatment, kinetic/isotherm analysis.

Reactor Design

Continuous reactors (fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, CSTR)

Steady influent/effluent; scalable; requires hydrodynamic and regeneration considerations.

In industrial applications, fixed-bed systems are widely used for large-scale adsorption processes.

Toxicological Assessments

Identification of by-products

Analytical tools (LC-MS, GC-MS, FTIR, and NMR) to detect degraded intermediates.

Ensures that no harmful or persistent by-products remain after treatment.

Toxicological Assessments

Bioassays

Tests on algae, Daphnia, fish embryos, or cell cultures for acute/chronic toxicity.

Evaluates the real environmental and health impact of effluent.

Toxicological Assessments

Risk assessment

Compare concentrations to permissible limits (PNEC, WHO, EPA standards).

Confirms treated water is safe for discharge or reuse.

4.1. Physical Methods There are different methods, such as adsorption, membrane filtration, and sedimentation, that are expected to remain central to dye removal due to their operational simplicity and broad applicability [93]. Adsorption, in particular, is widely favored because of its cost-effectiveness and versatility. The future direction of adsorption-based treatment lies in the development of low-cost, renewable adsorbents such as biochar, activated carbon from agricultural waste, magnetic composites, and nanostructured materials [94]. These innovations aim to improve adsorption capacity, reduce material cost, and facilitate regeneration for multiple cycles. Moreover, the potential for scaling up physical methods makes them suitable for small- to medium-scale industries, particularly in decentralized settings [93]. However, limitations such as adsorbent saturation, disposal issues, and regeneration cost persist. Future research must address these challenges by improving adsorbent recovery and reusability, particularly in magnetic and photocatalytic systems [94]. 4.2. Chemical Methods The prospect of chemical methods such as coagulation–flocculation, ozonation, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) is also promising for dye removal due to their ability to degrade complex dye molecules into less harmful by-products [95]. Future research in this area is anticipated to emphasize sustainable and environmentally friendly approaches, including the utilization of green coagulants, nanocatalysts, and LED-based visible-light-driven photocatalysis [96]. These innovations can enhance the degradation efficiency while reducing energy costs and chemical residues. Despite these advantages, chemical methods face economic and practical constraints, particularly in terms of high energy consumption, chemical usage, and operational complexity [97]. Nevertheless, improvements in catalyst recovery systems, low-cost oxidants, and integration with renewable energy sources could significantly enhance the cost-effectiveness and scalability of chemical treatments in the near future [98]. 4.3. Biological Methods While the future of biological methods offers an environmentally sustainable and economically attractive approach to dye removal, particularly for low-concentration and biodegradable dyes [99]. These methods employ dye-degrading bacteria, fungi, algae, and enzymes, which can break down dyes into non-toxic metabolites [100]. The primary benefits of biological methods include low energy input, minimal chemical requirements, and ease of integration with natural systems like wetlands and bioreactors. Looking ahead, future developments may consist of genetically engineered microorganisms, enzyme immobilization, and microbial consortia tailored for specific dye types and wastewater characteristics [101]. However, biological methods are still limited by slow degradation rates, sensitivity to environmental changes, and lower efficiency for non-biodegradable dyes. Hybrid approaches, where biological processes are combined with physical or chemical pre-treatment steps, are likely to emerge as a viable solution to overcome these limitations and enhance overall efficiency and applicability [102]. 4.4. Emerging Technologies for Next-Generation Dye Treatment Next-generation dye wastewater treatment is advancing beyond traditional physical, chemical, and biological processes, integrating smart materials, digital tools, and nanotechnology to improve efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability [103]. One promising approach is the use of machine learning (ML) for process optimization. ML algorithms can analyze large datasets from treatment processes to predict optimal operating conditions—such as pH, temperature, adsorbent dosage, and contact time—for maximum dye removal efficiency [104]. Techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and genetic algorithms are being used to model complex, nonlinear adsorption or degradation systems, thereby minimizing experimental costs and accelerating process design. Smart adsorbents are another breakthrough [105]. These materials, often stimuli-responsive (e.g., pH- or temperature-sensitive), can selectively adsorb dyes and regenerate under specific triggers. For example, thermo-responsive hydrogels or magnetic biochar composites can be easily separated and reused, making dye removal more sustainable [106]. Their tunable surface properties and selective binding capabilities offer significant advantages in complex textile effluents. Bio-nanomaterials, which integrate principles of biotechnology and nanotechnology, possess large surface areas, a wide variety of functional groups, and strong catalytic activity [107]. Enzyme-immobilized nanoparticles, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), and nano-biochar from agricultural waste are gaining attention for catalytic degradation and adsorption of synthetic dyes. These materials can act as nanozymes, mimicking enzymatic activity to break down resistant dye molecules under mild conditions. Hybrid systems that combine photocatalysis, biosorption, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) with smart materials are also gaining significant attention [108]. Such systems facilitate synergistic interactions that allow for the concurrent degradation of dyes and elimination of heavy metals, resulting in more comprehensive wastewater treatment. Eco-friendly dye treatment methods, such as bioadsorption and solar-driven photocatalysis, reduce energy consumption, minimize waste generation, and lower carbon emissions compared to conventional chemical processes. 4.5. Case Study Sustainability in wastewater treatment focuses on resource recovery, including the reuse of water, energy generation, and nutrient recovery, while minimizing the overall environmental burden. The concept of the carbon footprint plays a vital role by quantifying greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from different stages of treatment, such as aeration, sludge handling, and chemical dosing, thereby guiding industries toward the adoption of low-emission and energy-efficient technologies [109]. In parallel, machine learning (ML) offers significant advantages through predictive analytics, process optimization, and real-time tracking, allowing the industries to enhance operational efficiency, reduce costs, and minimize environmental impacts. In practice, these innovations are being increasingly integrated into industrial wastewater systems. For instance, in the textile hub of Tirupur, India, dyeing units have adopted zero-liquid-discharge (ZLD) plants that recycle nearly 90% of wastewater, reducing freshwater consumption and chemical load. Similarly, in the Netherlands, the Heineken brewery utilized anaerobic digestion of sewage to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels, resulting in an approximate 40% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions. In the USA, petrochemical plants have applied ML-based models to predict pollutant fluctuations such as COD and TSS, optimize coagulant dosing, and dynamically control aeration, resulting in around 20% energy savings and improved regulatory compliance [110]. Together, these cases demonstrate how sustainability, carbon footprint management, and machine learning can be effectively integrated to create efficient, low-carbon, and adaptable wastewater solutions.

From an economic and practical standpoint, the photocatalytic process has emerged as an auspicious approach for treating low to moderate-strength dye wastewater, particularly in scenarios where significant color and toxicity reduction is required. Despite the relatively high initial investment needed for photocatalyst materials and reactor systems, the long-term advantages, including reduced chemical usage, effective harnessing of solar energy, and limited secondary pollution, position photocatalysis as a promising and sustainable technology for advanced dye removal. Its practical application is increasingly evident in real effluent systems, especially when deployed as a pre- or post-treatment step in hybrid configurations, where it works synergistically with adsorption or biological methods to enhance overall treatment efficiency. Looking ahead, the future of photocatalytic dye removal lies in material science innovations, such as the development of 2D nanostructures, heterojunction photo catalysts, and photoelectrocatalytic systems, which offer improved degradation rates, selectivity, and reusability under visible light. In parallel, the use of combined adsorbents—composites derived from natural or modified materials—have demonstrated significant potential in enhancing dye removal performance, often surpassing the capabilities of single-component adsorbents. These materials are typically derived from readily available and low-cost raw sources, making them particularly attractive for large-scale industrial applications. Their economic feasibility and ease of preparation support their integration into existing wastewater treatment frameworks. Future research should focus on optimizing their surface properties, functional group interactions, and regeneration capabilities to handle the diverse and complex nature of industrial dye effluents.

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| AOP | Advanced Oxidation Processes |

| BOD | Biological Oxygen Demand |

| CB | Conduction Band |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CR | Congo Red |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diodes |

| MB | Methylene Blue |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Frameworks |

| OH | Hydroxyl Radicals |

| PFO | Pseudo-First-Order |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solid |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VB | Valence Band |

| ZLD | Zero-Liquid-Discharge |

Conceptualization, methodology, software: D.B.P. and A.K.; Validation, formal analysis, A.K.; Investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration: G.L.D. and D.B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

The authors A.K., G.L.D., and D.B.P. are thankful to HBTU Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, for the necessary facilities.

[1] Saxena, S.; Raja, A.S.M. Natural Dyes: Sources, Chemistry, Application and Sustainability Issues. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Eco-Friendly Raw Materials, Technologies, and Processing Methods; Springer: Singapore, 2014; pp. 37–80. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-287-065-0_2

[2] Singh, K.; Arora, S. Removal of Synthetic Textile Dyes from Wastewaters: A Critical Review on Present Treatment Technologies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 807–878. [CrossRef]

[3] Fried, R.; Oprea, I.; Fleck, K.; Rudroff, F. Biogenic Colourants in the Textile Industry–A Promising and Sustainable Alternative to Synthetic Dyes. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 13–35. [CrossRef]

[4] Travis, A.S. William Henry Perkin: A Teenage Chemist Discovers How to Make the First Synthetic Dye from Coal Tar. Text. Chem. Color. 1988, 20, 13. https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A8%3A34872680/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A31810351&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com

[5] Khan, S.; Malik, A. Environmental and Health Effects of Textile Industry Wastewater. In Environmental Deterioration and Human Health: Natural and Anthropogenic Determinants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 55–71. [CrossRef]

[6] Jorge, A.M.; Athira, K.K.; Alves, M.B.; Gardas, R.L.; Pereira, J.F. Textile Dyes Effluents: A Current Scenario and the Use of Aqueous Biphasic Systems for the Recovery of Dyes. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104125. [CrossRef]

[7] Omidoyin, K.C.; Jho, E.H. Environmental Occurrence and Ecotoxicological Risks of Plastic Leachates in Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176728. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8] Ahmed, M.; Mavukkandy, M.O.; Giwa, A.; Elektorowicz, M.; Katsou, E.; Khelifi, O.; Naddeo, V.; Hasan, S.W. Recent Developments in Hazardous Pollutants Removal from Wastewater and Water Reuse within a Circular Economy. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

[9] Ma, B.; Martín, C.; Kurapati, R.; Bianco, A. Degradation-by-Design: How Chemical Functionalization Enhances the Biodegradability and Safety of 2D Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6224–6247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10] Haleem, A.; Shafiq, A.; Chen, S.Q.; Nazar, M. A Comprehensive Review on Adsorption, Photocatalytic and Chemical Degradation of Dyes and Nitro-Compounds over Different Kinds of Porous and Composite Materials. Molecules 2023, 28, 1081. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11] Singha, K.; Pandit, P.; Maity, S.; Sharma, S.R. Harmful Environmental Effects for Textile Chemical Dyeing Practice. In Green Chemistry for Sustainable Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 153–164. [CrossRef]

[12] Piaskowski, K.; Świderska-Dąbrowska, R.; Zarzycki, P.K. Dye Removal from Water and Wastewater Using Various Physical, Chemical, and Biological Processes. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 1371–1384. [CrossRef]

[13] Abraham, W.R. Megacities as Sources for Pathogenic Bacteria in Rivers and Their Fate Downstream. Int. J. Microbiol. 2011, 2011, 798292. [CrossRef]

[14] Archana, C.M.; Kanakalakshmi, A.; Nithya, K.; Kaarunya, E.; Renugadevi, K. Health Effects of Emerging Contaminants: Effects on Humans Via Ingestion of Contaminated Water. In Emerging Contaminants in Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 269–306. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-89591-3_9

[15] Kumar, A.; Kapoor, A.; Rathoure, A.K.; Devnani, G.L.; Pal, D.B. Organic Compounds Removal using Magnetic Biochar from Textile Industries based Wastewater-A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Process. Connect. 2025, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

[16] Mota, A.F.; Miranda, M.M.; Moreira, V.R.; Moravia, W.G.; de Paula, E.C.; Amaral, M.C. Rejuvenated End-of-Life Reverse Osmosis Membranes for Landfill Leachate Treatment and Reuse Water Reclamation. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 105963. [CrossRef]

[17] Shen, Y.; Fang, Q.; Chen, B. Environmental Applications of Three-Dimensional Graphene-Based Macrostructures: Adsorption, Transformation, and Detection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 67–84. [CrossRef]

[18] Boyer, T.H.; Singer, P.C. Stoichiometry of Removal of Natural Organic Matter by Ion Exchange. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 608–613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19] Comstock, S.E.; Boyer, T.H.; Graf, K.C. Treatment of Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis Concentrates: Comparison of Precipitative Softening, Coagulation, and Anion Exchange. Water Res. 2011, 45, 4855–4865. [CrossRef]

[20] Phin, H.Y.; Ong, Y.T.; Sin, J.C. Effect of Carbon Nanotubes Loading on the Photocatalytic Activity of Zinc Oxide/Carbon Nanotubes Photocatalyst Synthesized via a Modified Sol-Gel Method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103222. [CrossRef]

[21] Freeman, H.S.; Mock, G.N. Dye Application, Manufacture of Dye Intermediates and Dyes. In Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 475–548. [CrossRef]

[22] Chequer, F.M.D.; de Oliveira, G.A.R.; Ferraz, E.R.A.; Cardoso, J.C.; Zanoni, M.V.B.; de Oliveira, D.P. Textile Dyes: Dyeing Process and Environmental Impact. In Eco-Friendly Textile Dyeing and Finishing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [CrossRef]

[23] Tariq, A.; Mushtaq, A. Untreated Wastewater Reasons and Causes: A Review of Most Affected Areas and Cities. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2023, 23, 121–143. https://www.iscientific.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/15-IJCBS-23-23-22.pdf

[24] El-Kashouti, M.; Elhadad, S.; Abdel-Zaher, K. Printing Technology on Textile Fibers. J. Text. Color. Polym. Sci. 2019, 16, 129–138. [CrossRef]

[25] Jain, S.; Jain, P.K. Classification, Chemistry, and Applications of Chemical Substances That Are Harmful to the Environment: Classification of Dyes. In Impact of Textile Dyes on Public Health and the Environment; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 20–49. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/classification-chemistry-and-applications-of-chemical-substances-that-are-harmful-to-the-environment/240896

[26] Mellor, A.; Olpin, H.C. Developments in the Application of Dyes to Cellulose Acetate Rayon. J. Soc. Dye. Colour. 1951, 67, 620–630. [CrossRef]

[27] Gupta, V.K.; Ali, I.; Saleh, T.A.; Nayak, A.; Agarwal, S. Chemical Treatment Technologies for Waste-Water Recycling—An Overview. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6380–6388. [CrossRef]

[28] Kumar, A.; Devnani, G.L.; Pal, D.B. Water hyacinth stem-based bioadsorbent for dye removal from synthetic wastewater: Adsorption kinetic study. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025, 1–19. [CrossRef]

[29] Ahmad, A.; Mohd-Setapar, S.H.; Chuong, C.S.; Khatoon, A.; Wani, W.A.; Kumar, R.; Rafatullah, M. Recent Advances in New Generation Dye Removal Technologies: Novel Search for Approaches to Reprocess Wastewater. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30801–30818. [CrossRef]

[30] Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Rui, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes for Water Purification. Polymers 2019, 11, 1252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[31] Al-Duri, B.; McKay, G. Adsorption Modeling and Mass Transfer. In Use of Adsorbents for the Removal of Pollutants from Wastewaters; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; pp. 138. https://books.google.com.pk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ep5bLsOs4IwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA133&dq=Al-Duri,+B.%CD%BE+McKay,+G.+Adsorption+Modeling+and++Mass+Transfer.+In+Use+of+Adsorbents+for+the+Removal++of+Pollutants+from+Wastewaters%CD%BE+CRC+Press:+Boca++Raton,+FL,+USA,+1996%CD%BE+p.+138&ots=TpQ4ehOtUh&sig=dDvvGFHRt49SJWE1L9gJ8FEPrqU&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

[32] Yu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, M.Q. Effect of Dye Structure on the Interaction between Organic Flocculant PAN-DCD and Dye. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 1589–1596. [CrossRef]

[33] Raghu, S.; Basha, C.A. Chemical or Electrochemical Techniques, Followed by Ion Exchange, for Recycle of Textile Dye Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 324–330. [CrossRef]

[34] Wang, J.; Wang, J. Application of Radiation Technology to Sewage Sludge Processing: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 143, 2–7. [CrossRef]

[35] Aldana, J.C.; Acero, J.L.; Álvarez, P.M. Membrane Filtration, Activated Sludge and Solar Photocatalytic Technologies for the Effective Treatment of Table Olive Processing Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105743. [CrossRef]

[36] Rashidi, H.R.; Sulaiman, N.M.N.; Hashim, N.A.; Hassan, C.R.C.; Ramli, M.R. Synthetic Reactive Dye Wastewater Treatment by Using Nano-Membrane Filtration. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 55, 86–95. [CrossRef]

[37] Chang, H.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Chen, C.; He, Q.; Crittenden, J.C. Smart Ultrafiltration Membrane Fouling Control as Desalination Pretreatment of Shale Gas Fracturing Wastewater: The Effects of Backwash Water. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104869. [CrossRef]

[38] Wimalawansa, S.J. Purification of Contaminated Water with Reverse Osmosis: Effective Solution of Providing Clean Water for Human Needs in Developing Countries. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2013, 3, 75–89. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284804889_Purification_of_Contaminated_Water_with_Reverse_Osmosis_Effective_Solution_of_Providing_Clean_Water_for_Human_Needs_in_Developing_Countries

[39] An, T.; Yang, H.; Li, G.; Song, W.; Cooper, W.J.; Nie, X. Kinetics and Mechanism of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Degradation of Ciprofloxacin in Water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 94, 288–294. [CrossRef]

[40] Sala, M.; Gutiérrez-Bouzán, M.C. Electrochemical Techniques in Textile Processes and Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 2012, 629103. [CrossRef]

[41] Neyens, E.; Baeyens, J. A Review of Classic Fenton’s Peroxidation as an Advanced Oxidation Technique. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 98, 33–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42] Ogundele, O.D.; Oyegoke, D.A.; Anaun, T.E. Exploring the Potential and Challenges of Electro-Chemical Processes for Sustainable Waste Water Remediation and Treatment. Acadlore Trans. Geosci. 2023, 2, 80–93. [CrossRef]

[43] Nahiun, K.M.; Sarker, B.; Keya, K.N.; Mahir, F.I.; Shahida, S.; Khan, R.A. A Review on the Methods of Industrial Waste Water Treatment. Sci. Rev. 2021, 7, 20–31. [CrossRef]

[44] Carmen, Z.; Daniel, S. Textile Organic Dyes–Characteristics, Polluting Effects and Separation/Elimination Procedures from Industrial Effluents–A Critical Overview. In Organic Pollutants Ten Years After the Stockholm Convention—Environmental and Analytical Update; InTech: Toulon, France, 2012. [CrossRef]

[45] Li, P.; Zhao, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, P.; Huang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, T.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Recent Advances in the Development of Water Oxidation Electrocatalysts at Mild pH. Small 2019, 15, 1805103. [CrossRef]

[46] Ravelli, D.; Protti, S.; Albini, A. Energy and Molecules from Photochemical/Photocatalytic Reactions. An Overview. Molecules 2015, 20, 1527–1542. [CrossRef]

[47] Dutta, S.; Gupta, B.; Srivastava, S.K.; Gupta, A.K. Recent Advances on the Removal of Dyes from Wastewater Using Various Adsorbents: A Critical Review. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4497–4531. [CrossRef]

[48] Bhatia, D.; Sharma, N.R.; Singh, J.; Kanwar, R.S. Biological Methods for Textile Dye Removal from Wastewater: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 47, 1836–1876. [CrossRef]

[49] Polyák, P.; Urbán, E.; Nagy, G.N.; Vértessy, B.G.; Pukánszky, B. The Role of Enzyme Adsorption in the Enzymatic Degradation of an Aliphatic Polyester. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 120, 110–116. [CrossRef]

[50] Singh, R.L.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, R.P. Enzymatic Decolorization and Degradation of Azo Dyes–A Review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 104, 21–31. [CrossRef]

[51] Sutthisa, W.; Kunseekhaw, B.; Khankhum, S.; Pimvichai, P.; Yutthasin, R. Assessment of Trichoderma Species Isolated From Volcanic Soil of a Durian Field in Sisaket Province, Thailand for Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol Potential. Trends Sci. 2024, 21, 8452. [CrossRef]

[52] Löwenberg, J.; Zenker, A.; Baggenstos, M.; Koch, G.; Kazner, C.; Wintgens, T. Comparison of Two PAC/UF Processes for the Removal of Micropollutants from Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent: Process Performance and Removal Efficiency. Water Res. 2014, 56, 26–36. [CrossRef]

[53] Valenta, J.N.; Weber, S.G.; Elser, R.C. Chemical Control of Reaction Time in an Enzyme Assay and Feasibility of Enzyme Spot Tests. Anal. Chem. 1990, 62, 1947–1953. [CrossRef]

[54] Iyer, P.V.; Ananthanarayan, L. Enzyme Stability and Stabilization—Aqueous and Non-Aqueous Environment. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1019–1032. [CrossRef]

[55] Liu, Y.; Tay, J.H. Strategy for Minimization of Excess Sludge Production from the Activated Sludge Process. Biotechnol. Adv. 2001, 19, 97–107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[56] Pei, L.; Schmidt, M. Fast-Growing Engineered Microbes: New Concerns for Gain-of-Function Research? Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 207. [CrossRef]

[57] Evtugyn, G.A.; Budnikov, H.C.; Nikolskaya, E.B. Sensitivity and Selectivity of Electrochemical Enzyme Sensors for Inhibitor Determination. Talanta 1998, 46, 465–484. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[58] Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P450s and Other Enzymes in Drug Metabolism and Toxicity. AAPS J. 2006, 8, E12. [CrossRef]

[59] Sheldon, R.A.; Brady, D. Streamlining Design, Engineering, and Applications of Enzymes for Sustainable Biocatalysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8032–8052. [CrossRef]

[60] Haider, T.P.; Völker, C.; Kramm, J.; Landfester, K.; Wurm, F.R. Plastics of the Future? The Impact of Biodegradable Polymers on the Environment and on Society. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 50–62. [CrossRef]

[61] Franssen, M.C.; Steunenberg, P.; Scott, E.L.; Zuilhof, H.; Sanders, J.P. Immobilised Enzymes in Biorenewables Production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6491–6533. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[62] Capodaglio, A.G. Urban Wastewater Mining for Circular Resource Recovery: Approaches and Technology Analysis. Water 2023, 15, 3967. [CrossRef]

[63] Bal, G.; Thakur, A. Distinct Approaches of Removal of Dyes from Wastewater: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 1575–1579. [CrossRef]

[64] Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and Its Removal from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 209, 172–184. [CrossRef]

[65] Chang, Z.; Chen, X.; Peng, Y. The Adsorption Behavior of Surfactants on Mineral Surfaces in the Presence of Electrolytes–A Critical Review. Miner. Eng. 2018, 121, 66–76. [CrossRef]

[66] Alaqarbeh, M. Adsorption Phenomena: Definition, Mechanisms, and Adsorption Types: Short Review. RHAZES Green Appl. Chem. 2021, 13, 43–51. [CrossRef]

[67] Aljamali, N.M.; Khdur, R.; Alfatlawi, I.O. Physical and Chemical Adsorption and Its Applications. Int. J. Thermodyn. Chem. Kinet. 2021, 7, 1–8. [CrossRef]

[68] Almazrouei, A.R.S.B.O. Effect of Salinity, Electric and Magnetic Field on Phenol Removal Using Activated Carbon Derived from Phoenix dactylifera Bio-Waste. Ph.D. Thesis, Khalifa University of Science, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. https://khazna.ku.ac.ae/en/studentTheses/effect-of-salinity-electric-and-magnetic-field-on-phenol-removal--2/

[69] Adegoke, K.A.; Akinnawo, S.O.; Adebusuyi, T.A.; Ajala, O.A.; Adegoke, R.O.; Maxakato, N.W.; Bello, O.S. Modified Biomass Adsorbents for Removal of Organic Pollutants: A Review of Batch and Optimization Studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 11615–11644. [CrossRef]

[70] Saadi, R.; Saadi, Z.; Fazaeli, R.; Fard, N.E. Monolayer and Multilayer Adsorption Isotherm Models for Sorption from Aqueous Media. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 787–799. [CrossRef]

[71] Gupta, V.K.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Ribeiro Carrott, M.M.L.; Suhas. Low-Cost Adsorbents: Growing Approach to Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 39, 783–842. [CrossRef]

[72] Murphy, O.P.; Vashishtha, M.; Palanisamy, P.; Kumar, K.V. A Review on the Adsorption Isotherms and Design Calculations for the Optimization of Adsorbent Mass and Contact Time. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 17407–17430. [CrossRef]

[73] Al-Ghouti, M.; Khraisheh, M.A.M.; Ahmad, M.N.M.; Allen, S. Thermodynamic Behaviour and the Effect of Temperature on the Removal of Dyes from Aqueous Solution Using Modified Diatomite: A Kinetic Study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 287, 6–13. [CrossRef]

[74] Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A.Y. Generation and Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302–11336. [CrossRef]

[75] Venkatadri, R.; Peters, R.W. Chemical Oxidation Technologies: Ultraviolet Light/Hydrogen Peroxide, Fenton’s Reagent, and Titanium Dioxide-Assisted Photocatalysis. Hazard. Waste Hazard. Mater. 1993, 10, 107–149. [CrossRef]

[76] Asghari, S.; Ramezani, S.; Ahmadipour, M.; Hatami, M. Fabrication and Morphological Characterizations of Immobilized Silver-Loaded Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles/Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanocomposites. Des. Monomers Polym. 2013, 16, 349–357. [CrossRef]

[77] Ravikumar, K.; Pakshirajan, K.; Swaminathan, T.; Balu, K. Optimization of Batch Process Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology for Dye Removal by a Novel Adsorbent. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 105, 131–138. [CrossRef]

[78] Tripathi, S.; Hussain, T. Water and Wastewater Treatment through Ozone-Based Technologies. In Development in Wastewater Treatment Research and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 139–172. [CrossRef]

[79] Sumikura, M.; Hidaka, M.; Murakami, H.; Nobutomo, Y.; Murakami, T. Ozone Micro-Bubble Disinfection Method for Wastewater Reuse System. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 53–61. [CrossRef]

[80] Ledakowicz, S.; Paździor, K. Recent Achievements in Dyes Removal Focused on Advanced Oxidation Processes Integrated with Biological Methods. Molecules 2021, 26, 870. [CrossRef]

[81] Sung, S.; Dague, R.R. Laboratory Studies on the Anaerobic Sequencing Batch Reactor. Water Environ. Res. 1995, 67, 294–301. [CrossRef]

[82] Muthukumar, M.; Sargunamani, D.; Selvakumar, N.; Rao, J.V. Optimisation of Ozone Treatment for Colour and COD Removal of Acid Dye Effluent Using Central Composite Design Experiment. Dye. Pigm. 2004, 63, 127–134. [CrossRef]

[83] Chen, J.; Loeb, S.; Kim, J.H. LED Revolution: Fundamentals and Prospects for UV Disinfection Applications. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2017, 3, 188–202. [CrossRef]

[84] Rawat, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Tiwary, C.S.; Gupta, A.K. An LED-Driven Hematite/Bi4O5I2 Nanocomposite as an S-scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst for Efficient Degradation of Phenolic Compounds in Real Wastewater. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 1271–1286. [CrossRef]

[85] Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Kong, T.; Zhang, H.; Duan, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, S. Roles of Catalyst Structure and Gas Surface Reaction in the Generation of Hydroxyl Radicals for Photocatalytic Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 2770–2780. [CrossRef]

[86] Maldotti, A.; Molinari, A.; Amadelli, R. Photocatalysis with Organized Systems for the Oxofunctionalization of Hydrocarbons by O2. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3811–3836. [CrossRef]

[87] Rohatgi, K.K.; Singhal, G.S. Nature of Bonding in Dye Aggregates. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 1695–1701. [CrossRef]

[88] Zayat, M.; Garcia-Parejo, P.; Levy, D. Preventing UV-Light Damage of Light Sensitive Materials Using a Highly Protective UV-Absorbing Coating. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1270–1281. [CrossRef]

[89] Al Mazouzi, A.; Alamo, A.; Lidbury, D.; Moinereau, D.; Van Dyck, S. PERFORM 60: Prediction of the Effects of Radiation for Reactor Pressure Vessel and In-Core Materials Using Multi-Scale Modelling–60 Years Foreseen Plant Lifetime. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 241, 3403–3415. [CrossRef]

[90] Sharma, M.; Sharma, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kumar, R.; Umar, A.; Alkhanjaf, A.A.M.; Baskoutas, S. Microorganisms-Assisted Degradation of Acid Orange 7 Dye: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 6133–6166. [CrossRef]

[91] Farouk, H.U. Effect of Chloride and Sulfate Ions on Deactivation of TiO2 Anatase in Photocatalytic Treatment of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019. https://www.proquest.com/openview/521cfd64d7e2dea2a658a9a230a84f97/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

[92] Cheng, S.; Zhao, S.; Xing, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xia, H. Preparation of Magnetic Adsorbent-Photocatalyst Composites for Dye Removal by Synergistic Effect of Adsorption and Photocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 348, 131301. [CrossRef]

[93] Younas, F.; Mustafa, A.; Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Wang, X.; Younas, S.; Mohy-Ud-Din, W.; Ashir Hameed, M.; Mohsin Abrar, M.; Maitlo, A.A.; Noreen, S.; et al. Current and Emerging Adsorbent Technologies for Wastewater Treatment: Trends, Limitations, and Environmental Implications. Water 2021, 13, 215. [CrossRef]

[94] Gupta, V.K. Application of Low-Cost Adsorbents for Dye Removal–A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2313–2342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[95] Vieira, W.T.; de Farias, M.B.; Spaolonzi, M.P.; da Silva, M.G.C.; Vieira, M.G.A. Removal of Endocrine Disruptors in Waters by Adsorption, Membrane Filtration and Biodegradation. A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1113–1143. [CrossRef]

[96] Satyam, S.; Patra, S. Innovations and Challenges in Adsorption-Based Wastewater Remediation: A Comprehensive Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29964. [CrossRef]

[97] Bramsiepe, C.; Sievers, S.; Seifert, T.; Stefanidis, G.D.; Vlachos, D.G.; Schnitzer, H.; Muster, B.; Brunner, C.; Sanders, J.P.M.; Bruins, M.E.; et al. Low-Cost Small Scale Processing Technologies for Production Applications in Various Environments—Mass Produced Factories. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2012, 51, 32–52. [CrossRef]

[98] Khatami, M.; Iravani, S. Green and Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Nanophotocatalysts: An Overview. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2021, 41, 133–187. [CrossRef]

[99] Kokossis, A.C.; Yang, A. On the Use of Systems Technologies and a Systematic Approach for the Synthesis and the Design of Future Biorefineries. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2010, 34, 1397–1405. [CrossRef]

[100] Jafarinejad, S. A Framework for the Design of the Future Energy-Efficient, Cost-Effective, Reliable, Resilient, and Sustainable Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 13, 91–100. [CrossRef]

[101] Al-Gethami, W.; Qamar, M.A.; Shariq, M.; Alaghaz, A.N.M.; Farhan, A.; Areshi, A.A.; Alnasir, M.H. Emerging Environmentally Friendly Bio-Based Nanocomposites for the Efficient Removal of Dyes and Micropollutants from Wastewater by Adsorption: A Comprehensive Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2804–2834. [CrossRef]

[102] Mishra, A.; Takkar, S.; Joshi, N.C.; Shukla, S.; Shukla, K.; Singh, A.; Manikonda, A.; Varma, A. An Integrative Approach to Study Bacterial Enzymatic Degradation of Toxic Dyes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 802544. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[103] Memon, H.; Lanjewar, K.; Dafale, N.; Kapley, A. Immobilization of Microbial Consortia on Natural Matrix for Bioremediation of Wastewaters. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 14, 403–413. [CrossRef]

[104] Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Liang, M.; Guo, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Ying, H. Physical–Chemical–Biological Pretreatment for Biomass Degradation and Industrial Applications: A Review. Waste 2024, 2, 451–473. [CrossRef]

[105] Casini, M. Smart Buildings: Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology to Improve Energy-Efficiency and Environmental Performance; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296700506_Smart_Buildings_Advanced_Materials_and_Nanotechnology_to_Improve_Energy-Efficiency_and_Environmental_Performance_-_384_pages

[106] de Farias Silva, C.E.; da Gama, B.M.V.; da Silva Gonçalves, A.H.; Medeiros, J.A.; de Souza Abud, A.K. Basic-Dye Adsorption in Albedo Residue: Effect of pH, Contact Time, Temperature, Dye Concentration, Biomass Dosage, Rotation and Ionic Strength. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2020, 32, 351–359. [CrossRef]

[107] Asfaram, A.; Ghaedi, M.; Azqhandi, M.A.; Goudarzi, A.; Dastkhoon, M. Statistical Experimental Design, Least Squares-Support Vector Machine (LS-SVM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Methods for Modeling the Facilitated Adsorption of Methylene Blue Dye. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 40502–40516. [CrossRef]

[108] Peighambardoust, S.J.; Azari, M.M.; Pakdel, P.M.; Mohammadi, R.; Foroutan, R. Carboxymethyl Cellulose Grafted Poly (Acrylamide)/Magnetic Biochar as a Novel Nanocomposite Hydrogel for Efficient Elimination of Methylene Blue. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 15193–15209. [CrossRef]

[109] Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Dou, S. Bio-Nanotechnology in High-Performance Supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700592. [CrossRef]

[110] Rando, G. Design and Development of Smart Advanced Materials and Sustainable Technologies for Water Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Messina, Messina, Italy, 2023. https://iris.unime.it/handle/11570/3283350

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more