APA Style

Tanushri Chatterji, Tripti Singh, Namrata Khanna, Tanya Bhagat, Disha Tyagi, Riya Totlani. (2025). Microbial Bioremediation Strategies for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Sustainable Processes Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0005). https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.122304MLA Style

Tanushri Chatterji, Tripti Singh, Namrata Khanna, Tanya Bhagat, Disha Tyagi, Riya Totlani. "Microbial Bioremediation Strategies for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment". Sustainable Processes Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0005, https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.122304.Chicago Style

Tanushri Chatterji, Tripti Singh, Namrata Khanna, Tanya Bhagat, Disha Tyagi, Riya Totlani. 2025. "Microbial Bioremediation Strategies for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment." Sustainable Processes Connect 1 (2025): 0005. https://doi.org/10.69709/SusProc.2025.122304.

ACCESS

Review Article

ACCESS

Review Article

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0005

Tanushri Chatterji

tanushri.chatterji@imsuc.ac.in

Tripti Singh

drtriptisingh@imsuc.ac.in

Namrata Khanna

namratakhanna@azamcampus.org

Tanya Bhagat

Tanya_24.phd@mriu.ac.in

Disha Tyagi

tyagidisha564@gmail.com

Riya Totlani

Rtotlani27@gmail.com

1 Department of Biosciences, Institute of Management Studies Ghaziabad (University Courses Campus), Adhyatmik Nagar, NH-09, Uttar Pradesh, Ghaziabad 201015, India

2 M. A. Rangoonwala College of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, 2390-B, K.B. Hidayatullah Road, Azam Campus, Camp, Pune, Maharashtra 411001, India

3 School of Allied Health Sciences, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Manav Rachna Campus Rd, Faridabad, Haryana 121004, India

4 Department of Microbiology, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Ramgarhi Meerut, Uttar Pradesh 250001, India

5 Shriram Institute for Industrial Research, University Road, Delhi 110007, India

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Received: 17 Feb 2025 Accepted: 01 Aug 2025 Available Online: 02 Aug 2025 Published: 20 Sep 2025

Wastewater treatment uses various techniques to remove contaminants such as heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and organic substances—by-products of agriculture, industry, and human activity. Microbes play a crucial role in eliminating hazardous substances through a process known as bioremediation. Bioremediation is a novel and promising technology that offers several advantages over conventional techniques for waste removal. It is flexible, cost-effective, and eco-friendly, and thus holds great potential for wastewater treatment. A diversity of microbial organisms, like algae, fungi, yeast, and bacteria, perform methylation and have the ability to modify and detoxify pollutants. This review outlines microbial approaches to wastewater treatment and contextualizes them within physical, chemical, biological, and membrane-based treatment frameworks. Key microbial technologies include biodegradation and activated sludge systems. Despite these advancements, challenges remain. These limitations include inconsistent efficiency across varying environmental conditions, difficulties in scaling up from lab to field applications, and challenges in maintaining active microbial populations. The current article outlines various strategies employed for biodegradation, highlighting their efficacy, recent advancements, and the challenges associated with their implementation and commercialization.

Comprehensive overview of microbial strategies for sustainable wastewater treatment using microbial consortium. Explores advanced microbial biotechnologies, including biofilm reactors, microbial fuel cells, and membrane bioreactors for pollutant removal. Highlights the role of omics technologies (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) in optimizing microbes for enhanced bioremediation. Compares microbial and conventional wastewater treatment methods in terms of cost, scalability, and environmental impact. Discusses current challenges, future directions, and the potential integration of AI and CRISPR-based approaches in microbial wastewater treatment.

Water pollution and its treatment have become major global concerns. Contaminants are mainly released through industrial activities—such as fertilizer production, mining, and pesticide manufacturing—or as domestic effluents. The release of hazardous waste affects human health and disturbs the aquatic ecosystems. UN World Water Development Report of 2024 states that an estimated 80% of the wastewater that is released into the environment has been adequately treated, more so, in countries under the low- and middle-income group [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported in 2024 that over 2 billion people drink water contaminated with feces, causing nearly 485,000 deaths from diarrhea each year [2]. The UNEP Global Environment Outlook (2024) also reported that more than 60% of freshwater bodies across the world are either moderately or severely polluted, comprising a wide range of contaminants, from nutrient overloads (eutrophication) to emerging pollutants, namely pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and personal care products [3]. These alarming statistics necessitate urgent efforts to develop sustainable and efficient wastewater treatment (WWT) solutions. Recent developments in biological WWT encourage researchers to improve microbial bioremediation technologies to ensure the availability of purified water [4,5]. Microbial bioremediation offers an eco-friendly, cost-effective alternative that aligns with global initiatives, namely Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.3, aiming to halve the concentration of untreated wastewater as well as significantly enhance its recycling and safe reuse via nature-based solutions (NbS) [6]

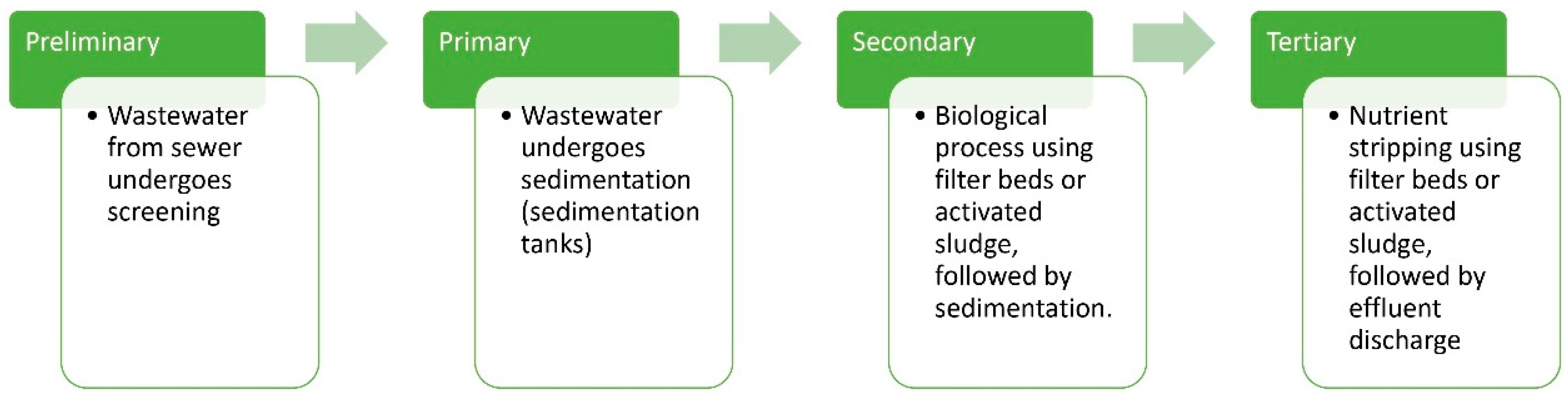

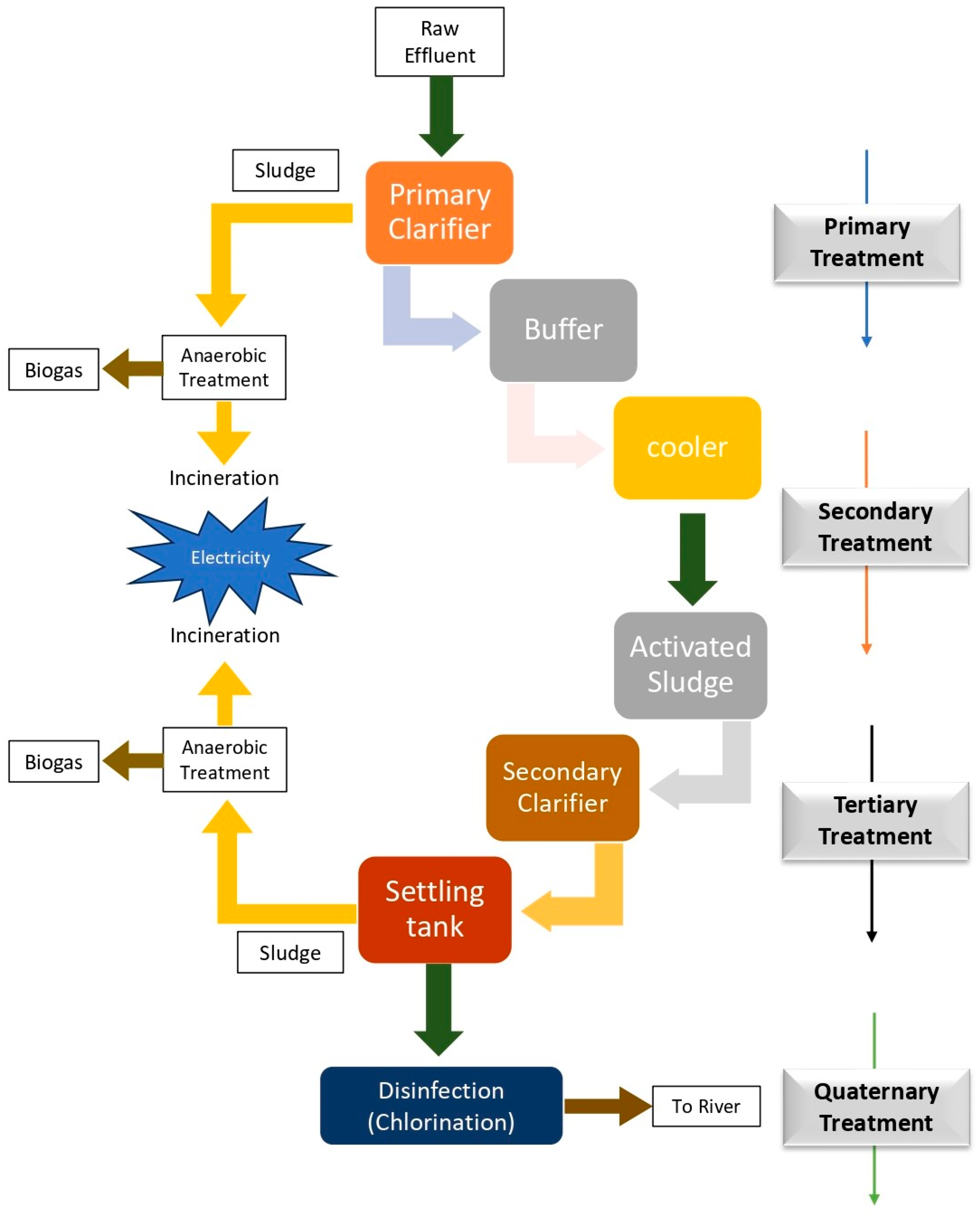

M. Robinson introduced the concept of using microorganisms for bioremediation [9]. The principle of biological remediation relies on biodegradation [10]. The process is commercially feasible and environmentally friendly, but its effectiveness varies with the region [11]. The microorganisms employed in bioremediation have the physiological ability to decompose and detoxify water contaminants [9,12]. It is an on-site, cost-effective strategy [13]. These microbial consortia can be generated by supplying nutrients, introducing electron acceptors, and modifying humidity and temperature in various ways [14]. During bioremediation, microorganisms utilize these contaminants as sources of nutrients or energy. In some cases, native microorganisms present at the site actively participate in the treatment process, while in other situations, specific microbial strains are introduced to the site through bioreactors [9]. Effective bioremediation depends on the proliferation and activity of microorganisms and environmental conditions affecting microbial development and degradation [12]. Therefore, in broad terms, bioremediation relies on selecting appropriate microorganisms at suitable sites for the efficient degradation of toxicants under optimal environmental conditions. By converting waste into carbon dioxide, biomass, water, or other non-toxic materials, bioremediation mineralizes waste and minimizes the requirement for further treatment [12]. Figure 1 illustrates the various stages of wastewater treatment, which are categorized into preliminary, primary, secondary, and tertiary processes. Besides processing urban debris and wastewater, microorganisms can also decompose pesticides, chemical waste generated from agriculture, fuel remnants, and imperishable compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons, chlorinated solvents, and several organic materials. During the process, microorganisms may be introduced into the polluted site from their place of origin, or they may be isolated and endemic in the polluted area. Microbial population transforms contaminants through reactions involved in their metabolism. Behavior of several microbial species is also a major factor involved in the biodegradation of a contaminant [12,15].

Water contaminants comprise domestic and industrial waste, and can be broadly classified as chemical pollutants, pharmaceutical contaminants, and irrigation discharges. They constitute infectious agents, microbial toxins, and spores in water bodies that affect the day-to-day water requirements [16]. Certain microbial pathogens that contribute to water pollution are responsible for causing waterborne diseases. These organisms include fungi, bacteria, protozoa, viruses, roundworms, and flatworms [5]. Enterococcus faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa account for opportunistic pathogens, which affect immunocompromised patients and cause systemic infection. Moreover, Shigella and Salmonella sp. or strains of Escherichia coli are leading causes of waterborne diseases [17,18].

4.1. Inorganic Chemicals Various pollutants exist under this category, including heavy metals, hydrocarbons, inorganic anions, pesticides, radioactive substances, cosmetics, and medication. Their presence can lower water suitability for use by biological organisms residing in large concentrations. Industrial waste with Hg, Cd, and Cr, agricultural and domestic waste containing nitrogen, along with naturally occurring F, As, and B, can be considered as sources. Human activities like substandard sanitation, hazardous farming methods, and industrial wastes lead to the addition of heavy metals to water [19]. Inorganic contaminants are not easily decomposed; they gradually settle into the aquatic environment and become hazardous to aquatic life. The category of inorganic water pollutants is composed of heavy metal halides, trace elements, radioactive compounds, inorganic salts, cyanides, sulfates, cations, and oxyanions [19,20,21]. Massive amounts of hazardous heavy metals and other contaminants, like As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Co, Hg, Ni, Pb, Sn, and Zn, are found in industrial effluent. Toxic heavy metals may originate from various sources, including mine waste, electroplating, hospital waste, sewage, smelters, battery factories, dye and alloy companies, and electronic factories. Natural or man-made sources of water might contain these heavy metals. Examples of natural causes include volcanic eruption, soil erosion, and rock disintegration, while human activities leading to water contamination include burning fossil fuels, mining, landfilling, urban water runoff, irrigation, processing of metals, manufacturing of printed circuit boards, colour dye production, and several other activities. Consequently, water is not accessible for use by common people [19,22,23]. 4.2. Organic Compounds Numerous chemical contaminants found in wastewater include pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, phenols, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heterocyclic aliphatic compounds, agricultural runoffs, bacteria, sewage, and effluents from the food processing industry. Wastewater from industrial and agricultural processes has organic components. It includes wastewater from farms that contain high levels of herbicides or pesticides, coke plant wastewater carrying different types of PAHs, chemical industry wastewater that contains different toxic compounds, including PCBs and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), food industry wastewater, and municipal wastewater. These organic contaminants in water pose a hazard to human health and the environment [19,24].

Anthropogenic and many industrial activities generate heavy metals, which contaminate water and cause severe harm to marine habitats. They are not biodegradable and harm animals and plants, which means they pose an appreciable risk to both life and the surroundings [4]. Pollutants can exert different effects depending on their sources and types. Certain types of waste, including dyes, heavy metals, and various organic contaminants, are known to be carcinogenic. Chemicals that damage the endocrine system and affect human and non-human animal reproduction and growth include some hormones, medicines, cosmetics, and waste generated from products of personal care [25]. The following are some detrimental effects of contaminated water on human health and the environment as a whole [26]: Health Impact ❖ One of the main causes of waterborne illnesses, such as cholera, typhoid, hepatitis A, and dysentery, is contaminated water. ❖ Cancer, neurological abnormalities, and disorders of reproduction are just a few of the severe health consequences that can result from exposure to harmful substances in contaminated water. Environmental Effects ❖ Water pollution may affect aquatic habitats, interfere with fish reproduction, and cause the death of fish. ❖ The loss of biodiversity is the result of all of these.Eutrophication, which results in algal blooms that lower water oxygen levels, can be brought on by an excess of nutrients from agricultural runoff Economic Impacts ❖ Reduced agricultural output, higher medical expenditures, and lost tourism revenue are just a few of the substantial financial consequences that water contamination can have. ❖ Fish populations are impacted by water pollution, which lowers harvests and causes financial losses for the fishing sector. ❖ The cost of eliminating contaminants from waterways and regenerating harmed ecosystems can be substantial. Other Effects ❖ There is a shortage of clean water available for drinking, irrigation, and industrial usage when freshwater sources are rendered unsuitable due to water pollution. ❖ This may make challenges with water scarcity worse.

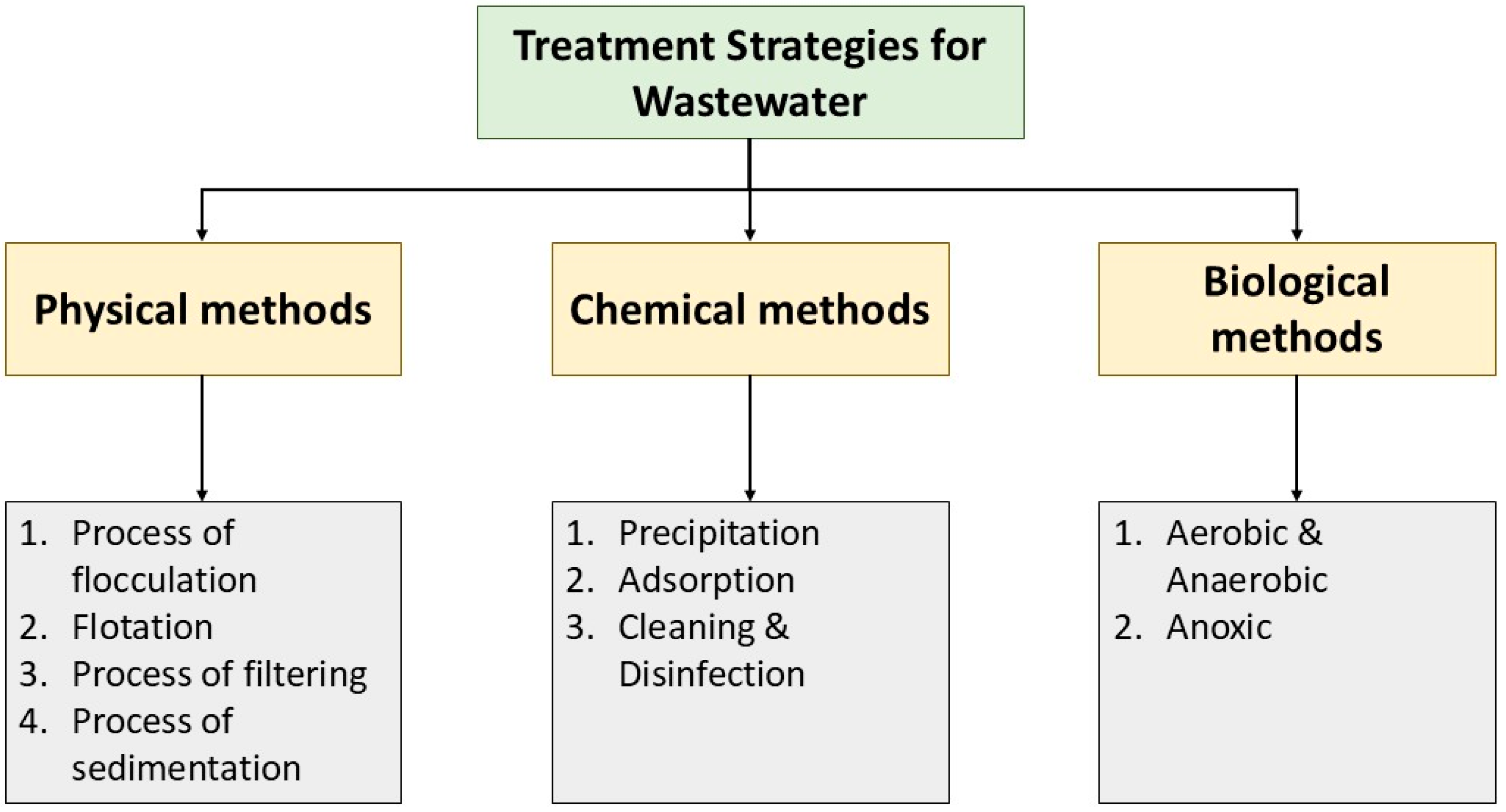

Major methodologies involved in treating the wastewater are physiological and biological processes. Conventional physicochemical methods employed are precipitation, evaporation. Osmosis, electrochemical treatment, ion exchange, and sorption (Figure 2). They are neither cost-effective nor environmentally friendly [27,28,29]. Biological methods are preferred as they are efficient in removing minute concentrations of metal ions and other waste materials.

Biological WWT is eco-compatible and cost-effective. It has a high metal binding potential of microbial consortium, which can remove heavy metals from a contaminated site effectively. It is highly effective even at low concentrations and has no adverse effects on aquatic ecosystems. Biological treatment is highly effective, as the microbial population easily adapts to the environment [28,30,31,32].

To safeguard both human health and the environment, microbial bioremediation rapidly and affordably immobilizes or eliminates pollutants [33,34,35]. Exogenous, specialized microorganisms or genetically modified microbes are being studied in various ways to improve the process [36]. Microbial remediation is capable of efficient and cost-effective contaminant removal, depending on various spatial and temporal factors, including the pollutant, the hydrogeologic environment, microbial ecology, and others. By adding nutrients (mainly nitrogen and phosphorus), oxygen as an electron acceptor, and substrates like toluene, phenol, and methane, or by presenting microbes with preferred catalytic properties, the bioremediation action through microbes is increased [37,38]. Therefore, in general, the bioremediation technique relies on locating the desired microorganisms at an appropriate location for efficient degradation under requisite environmental conditions. Biological treatment procedures turn trash into water, carbon dioxide, plant matter, or other benign compounds, thereby causing waste to mineralize and eliminating the need for additional treatment procedures. The term "bioremediation" refers to the handling of a wide variety of substances [12]. In addition to processing of urban trash and wastewater, microbial populations can also be employed for decomposition of pesticides, chemicals of agricultural waste, derivatives of fuel oil, and non-perishable compounds like chlorinated solvents, chlorofluorocarbons, and several more organic compounds. The metabolic activities of many organisms can also lead to the breakdown of chemicals [12].

Apart from the existing WWT techniques, microbial population plays a significant role in the degradation of water pollutants. Factors enhancing the technology involve the community of microorganisms, their structures, adaptability to the environmental conditions, and optimization of the biological systems. The potential of microbial WWT has become more stringent with the development of cultivation-independent techniques and a suite of molecular methods. Using the culture-independent techniques (DGGE: Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis) [39], molecular methods (T-RFLP, Cloning, FISH) [5,40,41] describe microbial community structure present in polluted water bodies. These techniques were entirely conducted using these molecular methods and metagenomic studies. Briefly, the research outcomes explained that removal of contaminants from activated sludge is promoted by phylum Proteobacteria, along with other groups like Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Planctomycetes, and many more in varied concentrations [42,43,44]. The basis of pollutant degradation involves carbohydrates, proteins, and amino acid derivatives or the metabolic products formed from aromatic compounds [45]. Key genera of microbes effective in wastewater treatment are summarized in Table 1(a–c). The major microbial species associated with efficient wastewater treatment (Figure 3) include lactic acid bacteria and photosynthetic bacteria [46]. The microbial consortium involved in bioremediation of wastewater includes several bacterial species like Arthrobacter, Achromobacter, Alcaligenes, Pseudomonas veronii, Acinetobacter, Corynebacterium, Flavobacterium, Micrococcus, Sphingomonas, Rhodococcus, Nocardia, Mycobacterium, Bacillus cereus, Kocuria flava, Sporosarcina ginsengisoli, Vibrio, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus lactis (lactic acid bacteria), Rhodopseudomonas palustris, and Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Photosynthetic bacteria). Fungal species like Penicillium canescens, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Aspergillus versicolor are also involved in the process of bioremediation. Yeasts like Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida utilis form part of the consortium. Algae like Cladophora fascicularis, Spirogyra sp., Cladophora sp., and Spirulina sp. are also involved in bioremediation [46,47,48,49].

Bacteria involved in the degradation of pollutants in wastewater treatment are predominantly aerobic, as their activity requires a significant amount of oxygen. Facultative and obligate anaerobes may also be present temporarily during treatment processes. Additionally, a few anaerobes, such as 18 species of Longilinea, Desulforhabdus, Georgenia, Thauera, Desulfuromonas, and Arcobacter genera, actively participate in the treatment processes and are released into the water bodies through sewage systems [50,51]. Among the anaerobes, Methanosarcina, Methanosaeta, and Clostridium are responsible for methane fermentation, though other species aid in the breakdown of complex organic macromolecules into simple compounds [52,53,54,55]. Bacteria are widely used in wastewater treatment, owing to a wide enzymatic activity and their prevalence in sewage water [56]. Bacterial cells typically range in size from 0.5 to 5 μm, depending on various shapes, like spherical, spiral, straight, and curved rods. Depending on their shape, the bacterial cells are observed singly, in pairs, or even in chains [57]. There are two major categories of bacteria: heterotrophic and autotrophic. Autotrophic bacteria utilize inorganic compounds as sources of carbon and energy, while heterotrophic bacteria such as Pseudomonas, Flavobacterium, Achromobacter, and Alcaligenes use organic materials. Heterotrophic bacteria are further classified based on their need for oxygen into: aerobic bacteria, which require free oxygen for the breakdown of organic matter, anaerobic bacteria, which grow in the absence of oxygen to break down organic matter, facultative bacteria, which disintegrate organic materials under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

Aerobic bacteria are most frequently employed for biological wastewater treatment, including trickling filters and activated sludge processes. The following equation describes the process: They facilitate the breakdown of organic matter. Such bacteria operate as autocatalysts and decompose organic matter under aerobic conditions. Based on factors such as pH, temperature, and the type of biological reactions involved, different concentrations of aerobic bacteria are used. Among these, the activated sludge process utilizes the highest concentration of bacteria. For converting a significant volume of feedstock in aerobic WWT, the activated sludge procedure is a straightforward and economically viable practice. Anaerobic bacteria have a substantially slower metabolic rate than aerobic bacteria. However, a major limitation of the process in aerobic conditions is the production of excessive biomass, often known as clarification sludge. In addition, it is quite cumbersome, to manage and dispose of this enormous amount of sludge, which has major environmental consequences, such as direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions. Further, excessive concentration of heavy metals and other hazards decreases the use of sludge as fertilizer for agriculture, necessitating its processing and treatment before final placement on land [58]. Moreover, dumping sludge in landfills can lead to the leaching of hazardous metals and organic pollutants into nearby soil and groundwater sources, thereby causing secondary pollution [59]. Several AGT (Advanced Green Technology) techniques are currently being applied either alone or in conjunction with conventional WWT techniques.

Fixed Bed Bioreactor- The multichambered tanks that collectively make up this bioreactor contain closely packed chambers of permeable porous plastic, ceramic, and foam. In this setup, wastewater flows over an immobilized media bed, which is composed with sufficient surface area for the development of a tough and resilient biofilm. This reduces the costs associated with sludge formation and removal [60,61]. Moving-Bed Bioreactor- These reactors have aeration tanks with small, polyethylene movable biofilm carriers that comprise an internally tethered vessel by sieves for media retention. These types of bioreactors can treat wastewater with an elevated Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) within a constrained space, eliminating the requirement for plugging. They are followed by a secondary clarifier, where extra sludge settles down, passes through a filter, and is then removed as solid waste [62]. Membrane Bioreactors- They employ an advanced technique for wastewater treatment (WWT), using membrane filtration to separate suspended solids more effectively than traditional methods such as sedimentation or settling. The concept of filtration enables effective operation with long solid residence times, enhanced mixed liquid suspended solids (MLSS), to produce significantly superior outcomes than the traditional activated sludge procedure [63]. Biological Trickling Filters- They work by pumping air or water through a medium of ceramics, foam, gravel, sand, and other materials. The media are designed to build up a surface biofilm. To accelerate the disintegration of organic compounds in air or water, biofilms can contain both aerobic and anaerobic microbes. This technique is frequently used to remove H2S from municipal wastewater [64]. Figure 4 gives a detailed representation of a wastewater treatment plant.

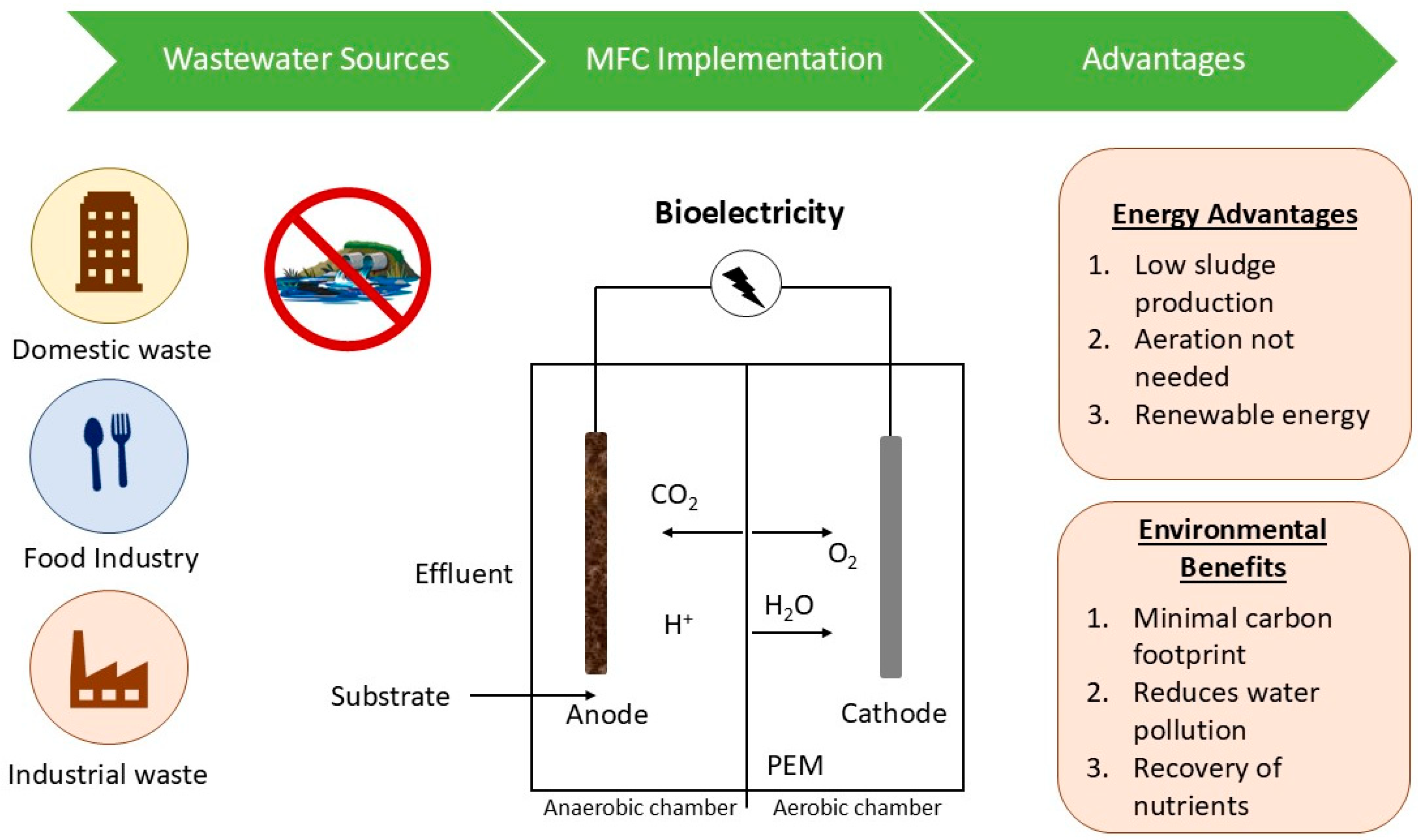

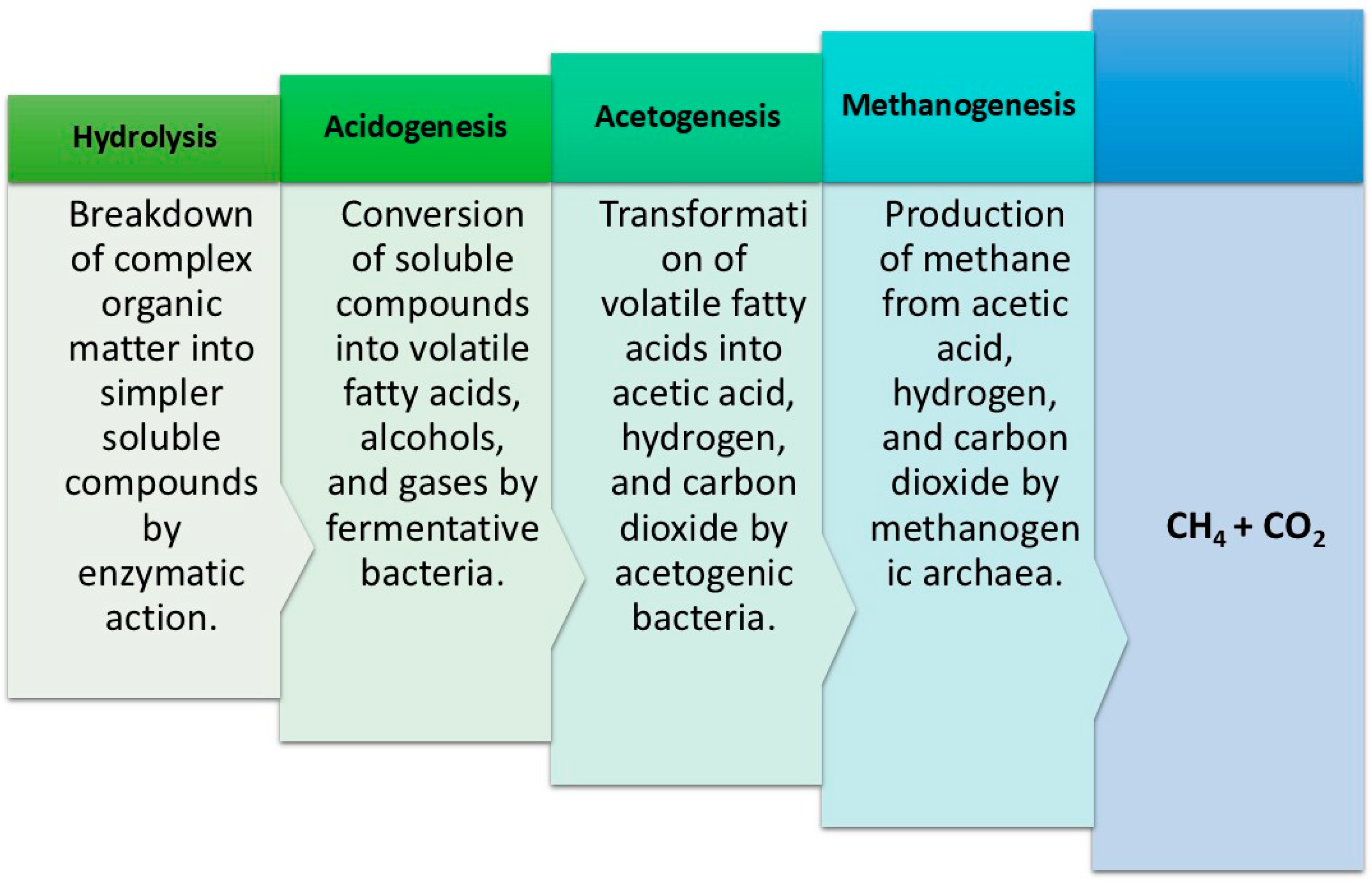

Due to strict environmental regulations and policies, anaerobic treatment has significantly increased in popularity despite the drawbacks of aerobic treatment, like high energy cost and sludge (Figure 5) [65]. Anaerobic bacteria decompose organic pollutants present in wastewater and derive energy from nitrates and sulphates [66] as depicted in Equations (2) and (3): These anaerobic reactions have a slower metabolic rate, necessitate a large population of bacteria, and take a very long time to reduce organic compounds [67]. However, the technique has many advantages [68,69]. Due to the absence of oxygen, aerosol formation is also prevented, making this method energy-efficient. More than 95% of the organic material is converted into combustible gases; hence, it provides a practical illustration of waste disposal. To optimize the advantages of both aerobic and anaerobic treatment methods, increasing attention is given to their strategic and precise integration. To obtain the desired result, several modifications have been explored to improve process efficiency [70]. A notable example is the combined approach of the two processes, in which one portion of wastewater is treated by aerobic processes and the other by anaerobic processes. This integrated methodology lowers P levels in the effluent along with the odour and sludge formation. Distillery treatment of wastewater is a prime example of a mixed process, which first performs anaerobic treatment to produce biogas before moving on to an aerobic process to meet wastewater regulations [65]. Additionally, one of the most significant and notable uses of microbes for WWT is the "Microbial Fuel Cell" (MFC) method of producing bioelectricity. It exemplifies cutting-edge technology for microbial metabolism-based generation of power [71]. This method makes use of microbes, particularly bacteria, to convert chemical energy created during the oxidation of organic and inorganic materials found in effluent into electrical energy. To effectively generate electricity from wastewater released by paper, agro-based, and dye industries, several bacteria, including Klebsiella pneumonia, Shewanella oneidensis, Nocardiopsis sp., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas sp., and Streptomyces enissocaesilis, are employed [72,73]. In an MFC, the cathode and anode compartments are typically separated by a proton exchange membrane, similar to other fuel cells [74]. Protons and electrons are released as a consequence of the oxidation of organic-containing wastewater in the anodic portion. By traversing the membrane and outer circuit, the electrons and protons migrate from anode to cathode, generating an electric current in the process. As a result, MFC is reliable for generating electricity as it is affordable (uses polluted water as a medium), clean, renewable, and produces no harmful byproducts [71,72].

"Fungi possess unique metabolic capabilities that enable them to degrade and eliminate a wide range of contaminants; therefore, fungal bioremediation presents a viable and sustainable approach to addressing environmental contamination. Laccases, peroxidases, and hydrolases are among the few of many enzymes that fungi possess and facilitate the degradation of heavy metals, complex organic compounds, and xenobiotics into less toxic forms. Due to their adaptability, fungi can be used in a variety of environmental settings, such as soil, water, and air remediation (Table 1b). Recently, the fungal phyla include: Ascomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Basidiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Entorrhizomycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mucoromycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiomycota, and Zoopagomycota [75,76,77].

Various microalgal species have demonstrated remarkable abilities for the bioremediation of nutrients, heavy metals, emerging contaminants, and pathogens from wastewater, including Chlorella, Phormidium, Limnospira (previously Arthrospira, Spirulina), and Chlamydomonas [78]. Photosynthetic microorganisms such as microalgae, eukaryotic algae, and cyanobacteria exhibit immense potential in the biodegradation of contaminated water [79]. This is an ecologically safe and sustainable technique for removing heavy metal contaminants, nutrients, and several organic pollutants from wastewater derived from municipal and industrial sources [80]. The technique involving algal species for biodegradation is called “phycoremediation” [81,82]. Chlorella vulgaris, Chlorella sp., Tetraselmis sp., Scenedesmus sp., Picochlorum sp., etc. are the algal species that are most frequently utilised for phycoremediation [83]. Anabaena species, Dolichospermum species, Hapalosiphon species, Scytonema species, Leptolyngbya species, Chroococcus species, Pseudospongiococcus species, Gloeocapsa species, Lyngbya species, Oscillatoria species, and Synechocystis species are among the several cyanobacterial strains.

Integrating resource recovery and energy production into the clean water generation process highlights the crucial role of archaea-based technologies in wastewater treatment. Archaea play a vital role in transforming contaminants into sustainable resources. Archaea remain poorly understood, especially compared to bacteria, which have been extensively studied in wastewater treatment systems. Insufficient literature is available that explains the metabolisms of a few significant archaea and the ecological patterns of archaea in a complex wastewater microbiome. Infrastructure Aging: Many WWTPs still use obsolete equipment, which results in inefficiencies and higher maintenance expenses. It will cost a lot of financial resources to upgrade these facilities [84].

17.1. Removal of Inorganic Constituents 17.1.1. Nitrogen Removal In WWT, nitrification (conversion of ammonia to nitrite and then to nitrate (nitrification)) and denitrification (conversion of nitrite or nitrate into gases like N2O and N2) are major mechanisms for the removal of nitrogen waste. The existence of ammonia and nitrite contribute to eutrophication and is harmful for aquatic bodies. Therefore, oxidation of ammonia is facilitated by aerobic and anaerobic oxidizers. The microbes involved in these processes are proteobacteria and anammox (ammonia oxidation) bacteria [85]. 17.1.2. Phosphorus Removal The concentration of phosphorus in water bodies gives rise to eutrophication and affects environmental conditions. The biological processes involved in the removal of phosphorus-containing waste involve enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR), and putative polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs). Microbes accumulate phosphorus intracellularly as polyphosphate and are then eliminated by wasting phosphorus-rich sludge. This process is facilitated by glycogen-accumulating organisms (GAOs) as they compete with PAOs [86]. 17.2. Organic Matter Removal Degradation of organic waste from contaminated water is enhanced in the presence of filamentous bacteria. These bacteria are specifically added to biological wastewater plants and bioreactors for waste removal. The removal is facilitated by the formation of bioflocs, a technology that improves the efficiency of fish feed utilization and maximize aquaculture productivity [87], particularly in activated sludge systems. They perform well in adverse conditions of reduced chemical oxygen demand or under substrate-limited circumstances. The active role of filamentous bacteria in the removal of organic matter became more stringent with the development of molecular techniques like FISH and high-throughput sequencing techniques. Excessive growth of filamentous bacteria causes operational problems in wastewater plants. The condition of this overgrowth is defined as bulking, which gives rise to deterioration in the settleability of bioflocs. As a result, the efficacy of the process is reduced; therefore, leads to poor pollutant separation in the final effluent [5,88]. 17.3. Carbon Mineralization Anaerobic digestion breaks down complex carbon compounds. The predominant genera involved in this method are archaea, which are often introduced into wastewater systems. They are prokaryotes, and the classified phylum involved are Euryarchaeota, which are currently grouped in the form of six established orders (Methanomicrobiales, Methanobacteriales, Methanopyrales, Methanococcales, Methanosarcinales, Methanocellales) and also as a proposed order (Methanomassiliicoccales). During the process, Archaea utilize restricted substrates like H2, CO2, methylated compounds, and acetate. It generates methane like a value-added by-product, which exclusively involves methanogenic archaea [5]. 17.4. Other Complex Molecules Moreover, a few bacteria have the potential to remove complex pollutants by generating electricity. There are some bacteria recognized for their ability to transfer electrons towards a working electrode and are categorized as microbial fuel cells (MFC). The operating principle is based on electrical performance and the mechanisms of electron and ion transport. Diversity in microbial populations within wastewater offers a broader range of MFC communities for the process. The efficiency of biodegradation through MFCs was supported by studies based on fingerprinting methods [89,90,91,92]. Depicts the microbial consortium involved in treating wastewater. Betaproteobacteria ammonia decomposers (like Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira) Gammaproteobacteria Nitrosococcus (except Nitrosococcus mobilis, which is a beta-proteobacterium) Alphaproteobacteria (like Nitrobacter 2014), Gammaproteobacteria (like Nitrosococcus) Nitrospirae (like Nitrospira) Alcaligenes Pseudomonas Methylobacterium Bacillus Paracoccus Hyphomicrobium Alphaproteobacteria (similar to ‘Nostocoida’), Gammaproteobacteria (e.g. Thiothrix and similar microbes) Chloroflexi Actinobacteria (Candidatus ‘Microthrix’, Mycolata) Nostocoida limicola’ I and II, Mycobacterium fortuitum Geobacter sp., Shewanella sp., Phototrophic bacteria (like Rhodopseudomonas sp.) Methanobacteriales, Methanococcales, Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales, Methanopyrales, Methanocellales Methanomassiliicoccales

Aspergillus niger -Trichoderma harzianum -Penicillium simplicissimum Phanerochaete chrysosporium Pleurotus ostreatus Trametes versicolor Pleurotus ostreatus Phanerochaete chrysosporium Trametes versicolor Bjerkandera adjusta Pleurotus sp. Pleurotus ostreatus Aspergillus fumigatus Phanerochaete chrysosporium Trichoderma harzianum Aspergillus oryzae Rhizopus spp. Trametes hirsuta Lentinula edodes Ganoderma lucidum Cladosporium resinae Aspergillus tubingensis Pestalotiopsis microspora Chlorella vulgaris Scenedesmus obliquus Chlorella pyrenoidosa Spirulina platensis Oscillatoria sp. Nostoc sp. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Anabaena cylindrica Chlorella minutissima Scenedesmus dimorphus, Ankistrodesmus sp. Spirulina maxima Chlorella ellipsoidea Dunaliella salina Botryococcus braunii Chlorella sorokiniana(a): Bacterial Consortium Treating Wastewater

Water Pollutants

Microbial Diversity

Mechanism of Action

Nitrogenous waste removal

Monophyletic classes-

Ammonia oxidation

Aerobic nitrite bacteria (NOB) -

Nitrification

Denitrification

Phosphorous waste removal

Acinetobacter

Putative PAO

Rhodocyclus related organisms

Enriched in EBPR reactors for phosphorous degradation.

Accumulibacter

Concerning phosphorus and carbon utilization by the microorganism.

Organic Matter Removal

Filamentous Bacteria

Complex molecules

Electrogenic Bacteria

Based on electrochemical activities of microbial communities.

Carbon Mineralization

Euryarchaeota

Generates a value-added by-product, methane.

(b): Significant Fungi in Treating Wastewater [77,93]

Water Pollutants

Fungi Species

Mechanism of Action

Heavy metals (e.g.Pb, Cd, Cr, Hg)

Release organic acids that chelate metals and facilitate the removal of heavy metals.

Hydrocarbons

These fungi are present in contaminated soil and possess ligninolytic enzymes. Laccase and peroxidase break down complex hydrocarbons into simpler compounds.

Dyes (e.g., azo, anthraquinone dyes)

Laccase and manganese peroxidase enzymes degrade the dyes.

Pesticides

Hydrolysis and oxidation through enzymatic pathways.

Pharmaceuticals (e.g., antibiotics)

Enzyme-based oxidation and hydroxylation; cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism.

Phenolic compounds

Oxidative breakdown mediated by peroxidases and laccases.

Nitrogenous compounds (e.g., ammonia, nitrates)

Assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction; ammonium assimilation.

Endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs)

Oxidation and polymerization using laccase.

Chlorinated compounds

Reductive dechlorination and enzymatic oxidation.

Microplastics & synthetic polymers

Depolymerization via hydrolases and esterases.

(c): Significant Algal species in Treating Wastewater [94]

Water Pollutants

Algal Species

Mechanism of Action

Heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn)

Biosorption and bioaccumulation through cell wall binding and intracellular uptake.

Nutrients (Nitrate, Phosphate)

Uptake via active transport and assimilation into biomass.

Dyes (e.g., methylene blue, Congo red)

Adsorption on mucilaginous sheath and enzymatic breakdown.

Pharmaceuticals & Personal Care Products (PPCPs)

Enzymatic degradation, sorption, and photodegradation.

Phenols & Aromatic Compounds

Biodegradation is facilitated by oxidative enzymes that incorporate substrates into metabolic pathways.

Pesticides (e.g., atrazine, lindane)

Biotransformation using detoxification enzymes.

Organic load (BOD, COD)

Reduction through oxygenation and microbial symbiosis enhances organic matter breakdown.

Oil and Hydrocarbons

Bioemulsification, adsorption, and partial degradation.

Endocrine Disruptors (e.g., Bisphenol A)

Laccase-like activity and photolytic transformation.

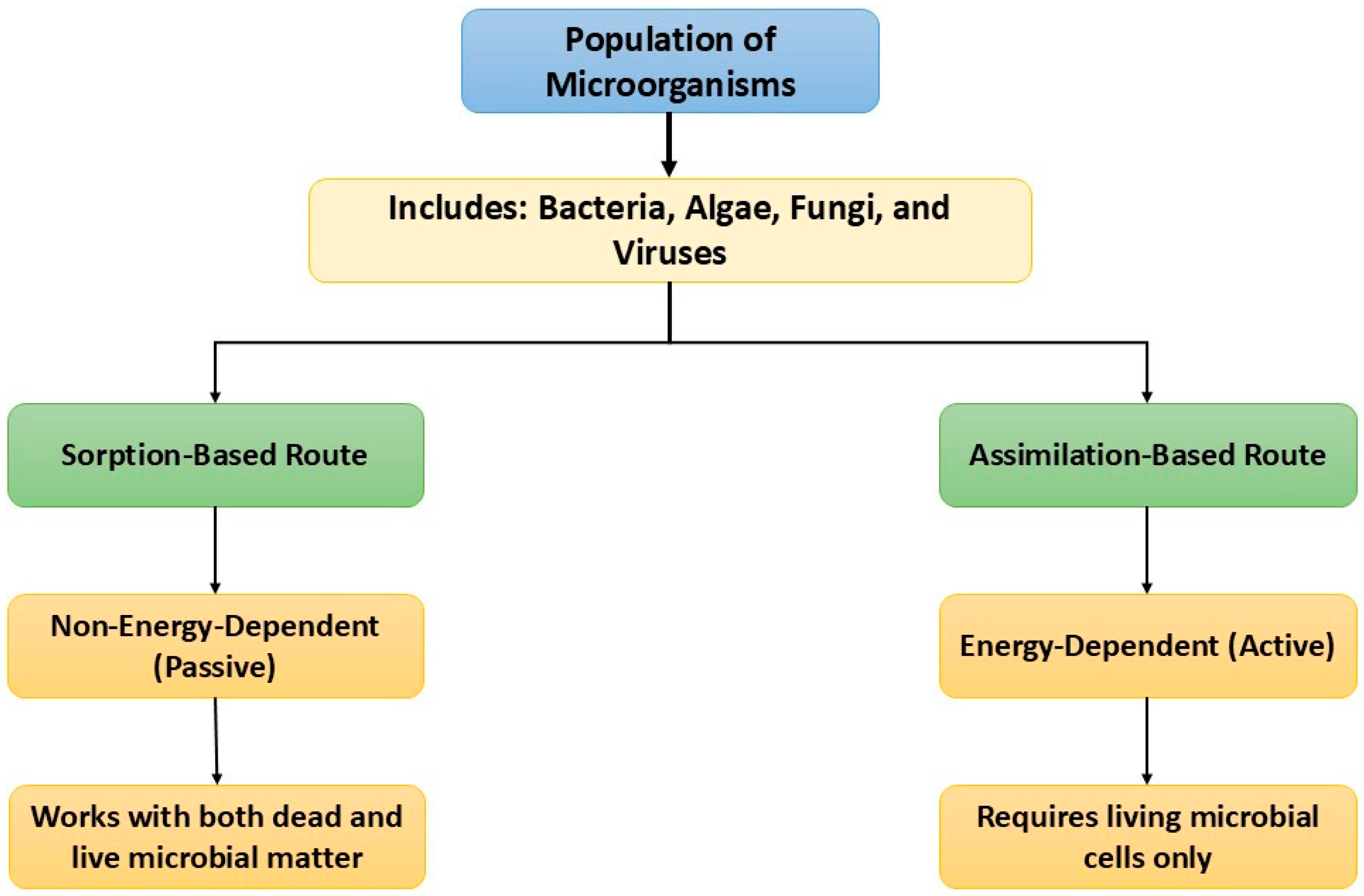

Bioremediation involves eukaryotes as well as prokaryotes in the elimination of toxic elements from water bodies. The methods employed and promoted in the biological transformation include bioleaching, bio-extraction, biosorption, bioencapsulation, and bioremediation [95,96]. Furthermore, bioremediation is classified as biosorption and bioaccumulation. These are based on the physicochemical interactions of microbes and pollutants. Factors affecting biosorption include pH, biomass concentration, temperature, and particle size [4]. Both dead and living biomass can be used in biosorption, which does not rely on cellular metabolism. Whereas, bioaccumulation involves intracellular and extracellular processes, in which passive uptake has a restricted and non-specific role [31]. Hence, living biomass is involved in bioaccumulation. This process (biosorption and bioaccumulation) is promoted by microbes (Figure 6), as they possess different macromolecules, like polysaccharides and proteins. They have many charged groups like thioether, carboxyl, sulfydryl, phenol, imidazole, carbonyl, amino, amide, ester sulfate, and hydroxyl [97,98]. The cell wall composition of microorganisms encourages the adsorption of the contaminants [31]. Therefore, algae act as biosorbents and produce less or negligible toxic substances [1]. The potential of microorganisms involved in biodegradation is mentioned in Table 2. The process of bioremediation is facilitated by complexation reactions, sorption, variation in pH, bioaccumulation, precipitation, and encapsulation.

Adoption of bioinformatics by using information from multiple biological databases, including databases of chemical structure and composition, RNA/protein expression, organic compounds, catalytic enzymes, microbial degradation pathways, and comparative genomics, could lead to the objectives of bioremediation [99]. All of these sources are interpreted using a range of bioinformatics methods to investigate bioremediation and develop more efficient environmental cleaning technologies. Only a small number of bioremediation applications have been made because of the lack of information on the variables influencing the growth and metabolism of microorganisms with bioremediation potential [100]. Bioinformatics has been used to map out the mineralization pathways and processes of these bioremediation-capable bacteria and to profile them [101]. Proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and genomics can all be used to enhance bioremediation investigations. These methods facilitate the assessment of the in-situ bioremediation process since it may correlate DNA sequences with the number of metabolites, proteins, and mRNA, leading to biomarker exploration also [102,103,104].

The study of bioremediation bacteria has given rise to a new area of genetics. This method is predicated on microorganisms’ capacity to thoroughly analyze their genetic material within cells. Numerous bacteria are used in bioremediation [105]. Genomic technologies like PCR, isotope distribution analysis, DNA hybridization, molecular connectivity, metabolic footprinting, and metabolic engineering are utilized to gain a better understanding of the biodegradation process. Amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP), amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA), automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (ARISA), terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP), randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (RAPD), single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP), and length heterogeneity are among the PCR-based methods available for genotypic fingerprinting. RAPD can be applied to the study of soil microbial communities to generate genetic fingerprints, build functional structural models, and evaluate naturally related bacterial species [106]. A combination of molecular techniques, including genetic fingerprinting, microradiography, FISH, stable isotope probing, and quantitative PCR, can also be used to study the interactions between pollutant bacteria and natural variables. The quantity and appearance of taxonomic and operational gene markers in the soil can be ascertained by quantitatively analyzing the soil microbial communities using PCR. Using cluster-assisted analysis, which analyzes fingerprints from several samples, it may be possible to gain a deeper understanding of the relationships between varied microbial populations [104].

The transcriptome is a vital connection between cellular phenotype, interactome, genome, and proteome that describes the association of genes under specific parameters. The ability to regulate gene expression is essential for environmental adaptation and, consequently, for survival. Transcriptomics provides a comprehensive understanding of this process across microbial genomes involved in bioremediation. DNA microarray analysis is a potent technique in transcriptomics for determining the amounts of mRNA expression [107].

Proteomics pertains to the total proteins expressed in a cell at a specific location and time, as opposed to metabolomics, which is involved with the total metabolites generated by an organism in a specific time or environment [108]. Proteomics has been used to identify important proteins linked to microbes, analyze protein abundance and compositional changes, and more [109]. Therefore, functional analysis of microbial communities involved in bioremediation becomes more practical and has greater potential than genomics. On the other hand, metabolomics studies are used to analyze biological systems. Implementing these approaches, the identification and recovery of a large number of metabolites in the sample produces an immense quantity of data that can be further utilized to demonstrate variations in the metabolic activity, physiological state, and adaptive responses of microorganisms under different environmental conditions [110].

The bioremediation approach has its advantages and disadvantages. A few of these are summarized below [104]: 23.1. Advantages of Bioremediation Naturally, waste treatment strategy for polluted materials like soil is time-consuming. The number of microorganisms that can break down the pollutant decreases. Though the byproducts, such as carbon dioxide, water, and cell biomass, are typically harmless to life forms or the environment. It requires minimal work and is frequently performed on-site regularly, without interfering with the regular microbial activity. This eliminates potential hazards to the environment and human health, as well as the quantity of waste that is transported off-site. In contrast to other traditional techniques that are frequently employed for the cleanup of toxic hazardous waste for the treatment of oil-contaminated regions, it operates cost-effectively. Additionally, it facilitates the full breakdown of pollutants; a large number of dangerous hazardous substances can be converted into less damaging products, and contaminated material can be disposed of. In the natural process, no hazardous chemicals are used. Fertilizers, in particular, are added to nutrients to promote rapid and vigorous microbial growth. The toxic compounds are completely eliminated due to bioremediation, which converts them into innocuous gases and water. Due to their inherent role in the environment, they are easy to use, less labour-intensive, and inexpensive. 23.2. Disadvantages of Bioremediation It is limited to biodegradable substances. Not all substances undergo a rapid and thorough breakdown process. Certain novel biodegradation products might be more hazardous than the original substances and persist in the environment. The bioremediation process is microbial consortium specific, which requires suitable environmental and optimal growth conditions for degradation. Promoting the process from bench and pilot-scale to large-scale field operations is a challenging task. There may be solids, liquids, or gases that are contaminants. It frequently takes longer than alternative treatment options like incineration or soil excavation and removal. Bacteria are used in the treatment of wastewater. 23.3. Limitations of Microbial-Dependent Remediation Only biodegradable compounds can undergo bioremediation, and not all break down quickly or completely. In the environment, biodegradation products could be more hazardous or persistent than the parent molecule [124]. Specificity- Biological processes depend on the availability of metabolically competent microbial populations, proper environmental growth conditions, and the right amounts of nutrients and pollutants are all crucial site elements that are necessary for success. Bulk Production- Scaling up the bioremediation process from pilot and batch scale investigations to large-scale field operations is challenging. Technological Enhancements- To develop novel engineered bioremediation methods that work at sites with composite combinations of toxins that are not evenly distributed in the environment, more study will be required. It could exist in the form of solids, liquids, or gases. Time Consuming- Compared to alternative treatment options, such as excavating and removing soil from a contaminated site, bioremediation is more time-intensive.S.No.

Bacteria/Species

/GenusBacterial Characteristics

Factors

Temperature/pH/Time/Inoculum Type of Pollutant

Degradation %

References

1.

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens

NSB4Bacillus amyloliquefaciens a Gram-positive, aerobic bacterium in soil

25 °C/ voltage below 300 mV/15 Days/40 mL inoculum

Organic pollutant

The obtained result showed a 90.46% reduction in COD of wastewater.

[111]

2.

Bacillus aryabhattai DDN

Bacillus aryabhattai is a rhizobacterium that promotes plant growth and colonizes plant roots.

pH 8–8.7

Sewage Water Pollutants

The obtained result showed a reduction in BOD (65.81%) and COD (58.02%) after 21 days

[112]

3.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Gram-negative, aerobic, rod-shaped bacterium

-

Dairy wastewater

The obtained result showed a 60% reduction in COD and BOD levels

[113]

4.

Pseudomonas zhanjiangensis

25A3E-

10 °C/96 h

The obtained result showed 72.9% success in removing chemical oxygen demand (COD), 70.6% success in removing ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4+-N), and 69.1% success in removing total nitrogen (TN)

[114]

5.

B. subtilis

Bacillus subtilis is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium/optimal growth temperature 30–35 °C

7.12 pH/72 h

Organic pollutant

The obtained result showed a reduction in

BOD from 352.18 to 32.56 mg/L

COD from 125.12 to 74.28 mg/L of wastewater.[115]

6.

Bacillus spizizenii DN

Gram-positive, rod-shaped/obligate anaerobe

-

Textile waste

waterThe obtained result showed 97.78% decolorization, whereas on adding

Bacillus spizizenii DN metabolites 82.92% decolorization was seen, post incubation of 48 h in microaerophilic conditions.[116]

7.

Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22

-

pH 8.0/30 °C

Phenol in wastewater

The obtained result showed 99.96% degradation of phenolic water.

[117]

8.

Bacillus

velezensisBacillus velezensis is a gram-positive, aerobic bacterium

Brewery wastewater-

The resulting bioflocculant exhibited effective wastewater treatment with removal success of 72.0% turbidity, 62.0% COD, and 53.6% BOD.

[118]

9.

Bacillus subtilis

-

-

Pharmaceutical wastewater

The Result obtained showed

COD reduction 150 mg/L from 395 mg/L initial raw wastewater value, and with a removal efficiency of 62.03% after 14 days.

BOD was reduced to 45 mg/L after 14 days with a reduction efficiency of 75.5%[119]

10.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

-

pH 5 and aluminium resistant up to 250 mg/L

Aluminium removal and recovery from wastewater

The obtained result showed 46.08 ± 1.95% of 50 mg/L aluminium removal by P. aeruginosa isolated from wastewater

[120]

11.

Bacillus sp. K5

-

Municipal wastewater treatment

The obtained result showed high efficiency in removing nutrients

e.g., for COD (90 ± 100%) and NH4+-N (85 ± 100%) removal was observed.[121]

12.

Serratia marcescens Abhi 001

A Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, which produces a red pigment at room temperature

18 h

Phenolic compound (P cresol) in wastewater

The obtained result showed 85% degradation of phenols in wastewater.

[122]

13.

Bacillus sterothermophilus ABO11

Bacillus stearothermophilus, also known as Geobacillus stearothermophilus/Prefer 30–75 °C temperature/Gram positive/rod shaped/spore forming

Maximum growth was observed at 40 °C, pH 8 and using NH4Cl

as a nitrogen sourceRemoval of phenol from wastewater

The result obtained showed 100% of degradation after 10 days.

[123]

The commercial application of microbial WWT depends on factors such as ecology, microbial diversity, implementation, mechanism of action, sensitivity, and specificity. Microbial treatment of wastewater is involved in both existing and conventional techniques, but the outcome is boosted by a better understanding of the microbial diversity, their metabolic and biological processes. Therefore, prospects can be improved through omics-based research. Genetic engineering, the development of novel microbial species using recombinant DNA technology, is a promising tool in bioremediation. These provide new insights into a host of complex and diverse microbial consortia. The emergence of biotechnological studies has improved knowledge of gene function, regulation, and metabolic potential. Efforts are currently underway to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a reliable and cost-effective manner. To overcome the existing gaps execution of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is anticipated to enhance the process of bioremediation [125]. Novel techniques such as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) can be utilized to integrate genetic data more effectively into computational modeling and system-level simulations. Hence, research in this field could lead to a better understanding of bioremediation processes.

| AGT | Advanced Green Technology |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| DGGE | Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EBPR | Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal |

| EDCs | Endocrine Disrupting Compounds |

| FISH | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

| GAOs | Glycogen-accumulating Organisms |

| MFC | Microbial Fuel Cell |

| MLSS | Mixed Liquid Suspended Solids |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| PAO | Polyphosphate-Accumulating Organisms |

| PBDE | Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated Biphenyls |

| T-RFLP | Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WWT | Wastewater Treatment |

T.C.: conceptualization, writing original draft; T.S.: conceptualization, writing original draft; N.K.: analysis, review, and editing; T.B.: conceptualization, review & editing; D.T.: conceptualization, review & editing; R.T.: review & editing; T.B and D.T.: designing and visualization of the figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. It is declared that all the figures used in the manuscript are original and self-drawn, though idea was taken from the published articles and references for the same has been mentioned.

Not applicable. This is a review article, and all data analyzed or discussed in this manuscript are derived from previously published studies, which are appropriately cited in the references.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

The authors are thankful to their respective institutes for allowing them to frame out this review article with their combined efforts.

[1] UNESCO WWDR. United Nations World Water Development Report 2024: Water for Prosperity and Peace United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2024. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2024

[2] WHO. Drinking Water Fact Sheet World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water

[3] Tiwari, A.K.; Pal, D.B. Chapter 11—Nutrients Contamination and Eutrophication in the River Ecosystem. In Ecological Significance of River Ecosystems; Madhav, S.; Kanhaiya, S.; Srivastav, A.; Singh, V.; Singh, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. pp. 203–216. [CrossRef]

[4] Coelho, L.M.; Rezende, H.C.; Coelho, L.M.; de Sousa, P.A.R.; Melo, D.F.O.; Coelho, N.M.M. Bioremediation of Polluted Waters Using Microorganisms. In Advances in Bioremediation of Wastewater and Polluted Soil; Shiomi, N., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2015. [CrossRef]

[5] Ferrera, I.; Sánchez, O. Insights into Microbial Diversity in Wastewater Treatment Systems: How Far Have We Come? Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 790–802. [CrossRef]

[6] Crowther, T.W.; Rappuoli, R.; Corinaldesi, C.; Danovaro, R.; Donohue, T.J.; Huisman, J.; Stein, L.Y.; Timmis, J.K.; Timmis, K.; Anderson, M.Z.; et al. Scientists’ call to action: Microbes, planetary health, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Cell 2024, 187, 5195–5216. [CrossRef]

[7] Pillay, T.V.R. Aquaculture and the Environment Halsted Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [CrossRef]

[8] Divya, M.; Aanand, S.; Srinivasan, A.; Ahilan, B. Bioremediation—An Eco-Friendly Tool for Effluent Treatment: A Review. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 530–537. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315802463_Bioremediation_-_An_eco-friendly_tool_for_effluent_treatment_A_Review (accessed on 24 January 2025).

[9] Amin, A.; Azhar, M. Bioremediation of Different Waste Waters—A Review. Cont. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 7, 7–17. [CrossRef]

[10] Abatenh, E.; Gizaw, B.; Tsegaye, Z.; Wassie, M. The Role of Microorganisms in Bioremediation—A Review. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Role-of-Microorganisms-in-Bioremediation-A-Abatenh-Gizaw/ac28d33819dd782d9e121040f4cdda57a86210e6 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

[11] Wang, Y.; Tam, N.F.Y. Chapter 16—Microbial Remediation of Organic Pollutants. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation; Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. pp. 283–303. [CrossRef]

[12] Zouboulis, A.; Moussas, P.; Psaltou, S. Groundwater and Soil Pollution: Bioremediation. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [CrossRef]

[13] Gupta, S.; Pathak, B. Chapter 6—Mycoremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. In Abatement of Environmental Pollutants; Singh, P.; Kumar, A.; Borthakur, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 127–149. [CrossRef]

[14] Kumar, A.; Bisht, B.S.; Joshi, V.; Dhewa, T. Review on Bioremediation of Polluted Environment: A Management Tool. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 1, 1079–1093. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284061537_Review_on_bioremediation_of_polluted_environment_A_management_tool (accessed on 24 January 2025).

[15] Ojha, N.; Karn, R.; Abbas, S.; Bhugra, S. Bioremediation of Industrial Wastewater: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 796, 012012. [CrossRef]

[16] Yadav, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, L.R.; Kaur, R.; Yellapu, S.K.; Sellamuthu, B.; Tyagi, R.D.; Drogui, P. Introduction to Wastewater Microbiology: Special Emphasis on Hospital Wastewater. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 1–41. [CrossRef]

[17] Cyprowski, M.; Szarapińska-Kwaszewska, J.; Dudkiewicz, B.; Krajewski, J.A.; Szadkowska-Stańczyk, I. Exposure assessment to harmful agents in workplaces in sewage plant workers. Med. Pr. 2005, 56, 213–222. [PubMed]

[18] Gerardi, M.H.; Zimmerman, M.C. Wastewater Pathogens Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. Available online: https://alameed.edu.iq/DocumentPdf/Library/eBook/6312.pdf

[19] Srivastav, A.L.; Ranjan, M. Chapter 1—Inorganic Water Pollutants. In Inorganic Pollutants in Water; Devi, P.; Singh, P.; Kansal, S.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

[20] Wasewar, K.L.; Singh, S.; Kansal, S.K. Chapter 13—Process Intensification of Treatment of Inorganic Water Pollutants. In Inorganic Pollutants in Water; Devi, P.; Singh, P.; Kansal, S.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 245–271. [CrossRef]

[21] Kumar, M.; Borah, P.; Devi, P. Chapter 3—Priority and Emerging Pollutants in Water. In Inorganic Pollutants in Water; Devi, P.; Singh, P.; Kansal, S.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 33–49. [CrossRef]

[22] Verma, R.; Dwivedi, P. Heavy Metal Water Pollution-A Case Study. Recent Res. Sci. Technol. 2013, 5, 98–99.

[23] Masindi, V.; Muedi, K. Environmental Contamination by Heavy Metals InTech: London, UK, 2018. [CrossRef]

[24] Zheng, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Fu, Z.; Li, A.Z. Treatment Technologies for Organic Wastewater. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Treatment-Technologies-for-Organic-Wastewater-Zheng-Zhao/8aec5411f0178cf573826580a51dfe079fd96968 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

[25] Gonsioroski, A.; Mourikes, V.E.; Flaws, J.A. Endocrine Disruptors in Water and Their Effects on the Reproductive System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1929. [CrossRef]

[26] Priyanka; Tiwari, R.C.; Dikshit, M.; Mittal, B.; Sharma, V.B. Effects of Water Pollution—A Review Article. J. Ayu Int. Med. Sci. 2022, 7, 63–68.

[27] Mulligan, C.N.; Yong, R.N.; Gibbs, B.F. Remediation Technologies for Metal-Contaminated Soils and Groundwater: An Evaluation. Eng. Geol. 2001, 60, 193–207. [CrossRef]

[28] Kadirvelu, K.; Senthilkumar, P.; Thamaraiselvi, K.; Subburam, V. Activated Carbon Prepared from Biomass as Adsorbent: Elimination of Ni(II) from Aqueous Solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 81, 87–90. [CrossRef]

[29] Fomina, M.; Gadd, G.M. Biosorption: Current Perspectives on Concept, Definition and Application. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 3–14. [CrossRef]

[30] Tsezos, M.; Volesky, B. Biosorption of Uranium and Thorium. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1981, 23, 583–604. [CrossRef]

[31] Gadd, G. Microbial Treatment of Metal Pollution? A Working Biotechnology? Trends Biotechnol. 1993, 11, 353–359. [CrossRef]

[32] Texier, A.C.; Andrès, Y.; Le Cloirec, P. Selective Biosorption of Lanthanide (La, Eu, Yb) Ions by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 489–495. [CrossRef]

[33] Heitzer, A.; Sayler, G. Monitoring the Efficacy of Bioremediation. Trends Biotechnol. 1993, 11, 334–343. [CrossRef]

[34] Gheewala, S.H.; Annachhatre, A.P. Biodegradation of Aniline. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 53–63. [CrossRef]

[35] Gadd, G.M. Bioremedial Potential of Microbial Mechanisms of Metal Mobilization and Immobilization. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000, 11, 271–279. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[36] Brim, H.; Venkateswaran, A.; Kostandarithes, H.M.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Daly, M.J. Engineering Deinococcus Geothermalis for Bioremediation of High-Temperature Radioactive Waste Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4575–4582. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[37] Ma, X.; Novak, P.J.; Ferguson, J.; Sadowsky, M.; LaPara, T.M.; Semmens, M.J.; Hozalski, R.M. The Impact of H2 Addition on Dechlorinating Microbial Communities. Bioremediation J. 2007 [CrossRef]

[38] Baldwin, B.R.; Peacock, A.D.; Park, M.; Ogles, D.M.; Istok, J.D.; McKinley, J.P.; Resch, C.T.; White, D.C. Multilevel Samplers as Microcosms to Assess Microbial Response to Biostimulation. Ground Water 2008, 46, 295–304. [CrossRef]

[39] Adrados, B.; Sánchez, O.; Arias, C.A.; Becares, E.; Garrido, L.; Mas, J.; Brix, H.; Morató, J. Microbial Communities from Different Types of Natural Wastewater Treatment Systems: Vertical and Horizontal Flow Constructed Wetlands and Biofilters. Water Res. 2014, 55, 304–312. [CrossRef]

[40] Sánchez, O.; Garrido, L.; Forn, I.; Massana, R.; Maldonado, M.I.; Mas, J. Molecular Characterization of Activated Sludge from a Seawater-Processing Wastewater Treatment Plant: Characterization of Seawater-Activated Sludge. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 628–642. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[41] Kämpfer, P.; Erhart, R.; Beimfohr, C.; Böhringer, J.; Wagner, M.; Amann, R. Characterization of Bacterial Communities from Activated Sludge: Culture-Dependent Numerical Identification versus in Situ Identification Using Group- and Genus-Specific rRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotide Probes. Microb. Ecol. 1996, 32, 101–121. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42] Snaidr, J.; Amann, R.; Huber, I.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.H. Phylogenetic Analysis and in Situ Identification of Bacteria in Activated Sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2884–2896. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[43] Boon, N.; Windt, W.; Verstraete, W.; Top, E.M. Evaluation of Nested PCR–DGGE (Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis) with Group-Specific 16S rRNA Primers for the Analysis of Bacterial Communities from Different Wastewater Treatment Plants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002, 39, 101–112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[44] Wang, X.; Wen, X.; Yan, H.; Ding, K.; Zhao, F.; Hu, M. Bacterial Community Dynamics in a Functionally Stable Pilot-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plant. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2352–2357. [CrossRef]

[45] Sanapareddy, N.; Hamp, T.J.; Gonzalez, L.C.; Hilger, H.A.; Fodor, A.A.; Clinton, S.M. Molecular Diversity of a North Carolina Wastewater Treatment Plant as Revealed by Pyrosequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1688–1696. [CrossRef]

[46] Narmadha, D.; Kavitha, V. Treatment of Domestic Waste Water Using Natural Flocculants. Environ. Sci. Indian J. 2012, 7, 173–178.

[47] Gupta, V.K.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Jain, N. Biosorption of Chromium(VI) from Aqueous Solutions by Green Algae Spirogyra Species. Water Res. 2001, 35, 4079–4085. [CrossRef]

[48] Kim, S.U.; Cheong, Y.H.; Seo, D.C.; Hur, J.S.; Heo, J.S.; Cho, J.S. Characterisation of Heavy Metal Tolerance and Biosorption Capacity of Bacterium Strain CPB4 (Bacillus Spp.). Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 105–111. [CrossRef]

[49] Jayashree, R.; Nithya, S.; Prasanna, P.R.; Krishnaraju, M. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312454419_Biodegradation_capability_of_bacterial_species_isolated_from_oil_contaminated_soil (accessed on 24 January 2025).

[50] Liu, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shi, H. Distribution and Population Structure Characteristics of Microorganisms in Urban Sewage System. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7723–7734. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[51] Cyprowski, M.; Stobnicka-Kupiec, A.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Bakal-Kijek, A.; Gołofit-Szymczak, M.; Górny, R.L. Anaerobic Bacteria in Wastewater Treatment Plant. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2018, 91, 571–579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[52] Zinder, S.H.; Mah, R.A. Isolation and Characterization of a Thermophilic Strain of Methanosarcina Unable to Use H2-CO2 for Methanogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 38, 996–1008. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[53] Wang, C.C.; Chang, C.W.; Chu, C.P.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, B.V.; Liao, C.S. Producing Hydrogen from Wastewater Sludge by Clostridium Bifermentans. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 102, 83–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[54] Lisle, J.T.; Smith, J.J.; Edwards, D.D.; McFeters, G.A. Occurrence of Microbial Indicators and Clostridium Perfringens in Wastewater, Water Column Samples, Sediments, Drinking Water, and Weddell Seal Feces Collected at McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 7269–7276. [CrossRef]

[55] van Lier, J.B.; Mahmoud, N.; Zeeman, G. Anaerobic Wastewater Treatment. In Biological Wastewater Treatment: Principles, Modelling and Design; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781780401867_A24149634/preview-9781780401867_A24149634.pdf

[56] Nascimento, A.L.; Souza, A.J.; Andrade, P.A.M.; Andreote, F.D.; Coscione, A.R.; Oliveira, F.C.; Regitano, J.B. Sewage Sludge Microbial Structures and Relations to Their Sources, Treatments, and Chemical Attributes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9 [CrossRef]

[57] Young, K.D. Bacterial Morphology: Why Have Different Shapes? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007, 10, 596–600. [CrossRef]

[58] Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Potential Benefits and Risks of Land Application of Sewage Sludge. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 347–358. [CrossRef]

[59] Pathak, A.; Dastidar, M.G.; Sreekrishnan, T.R. Bioleaching of Heavy Metals from Sewage Sludge: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2343–2353. [CrossRef]

[60] Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Dharmawan, F.; Palmer, C.G. Roles of Polyurethane Foam in Aerobic Moving and Fixed Bed Bioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1435–1439. [CrossRef]

[61] Chatterji, T.; Kumar, S. Chapter 20—Biofilm in Remediation of Pollutants. In Biological Approaches to Controlling Pollutants; Kumar, S.; Hashmi, M.Z., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022. pp. 399–417. Advances in Pollution Research. [CrossRef]

[62] Jaroszynski, L.W.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Oleszkiewicz, J.A. Impact of Free Ammonia on Anammox Rates (Anoxic Ammonium Oxidation) in a Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 188–195. [CrossRef]

[63] Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.L.; Wang, X.C.; Shen, J.M.; Xu, H. PPCPs Removal by Aerobic Granular Sludge Membrane Bioreactor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 9843–9848. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[64] Zhang, B.; Yu, Q.; Yan, G.; Zhu, H.; Xu, X.Y.; Zhu, L. Seasonal Bacterial Community Succession in Four Typical Wastewater Treatment Plants: Correlations between Core Microbes and Process Performance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4566. [CrossRef]

[65] Pant, D.; Adholeya, A. Biological Approaches for Treatment of Distillery Wastewater: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2321–2334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[66] Ji, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, H.; Kong, Z. Insights into the Bacterial Species and Communities of a Full-Scale Anaerobic/Anoxic/Oxic Wastewater Treatment Plant by Using Third-Generation Sequencing. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019, 128, 744–750. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[67] Wilkie, A.C.; Riedesel, K.J.; Owens, J.M. Stillage Characterization and Anaerobic Treatment of Ethanol Stillage from Conventional and Cellulosic Feedstocks. Biomass Bioenergy 2000, 19, 63–102. [CrossRef]

[68] Akunna, J.C.; Clark, M. Performance of a Granular-Bed Anaerobic Baffled Reactor (GRABBR) Treating Whisky Distillery Wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 74, 257–261. [CrossRef]

[69] Wolmarans, B.; De, V.G.H. Start-up of a UASB Effluent Treatment Plant on Distillery Wastewater. Water SA 2002, 28, 63–68. [CrossRef]

[70] Ranade, V.V.; Bhandari, V.M. Industrial Wastewater Treatment, Recycling, and Reuse: An Overview. In Industrial Wastewater Treatment, Recycling and Reuse; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. pp. 1–80. [CrossRef]

[71] Chaturvedi, V.; Verma, P. Microbial Fuel Cell: A Green Approach for the Utilization of Waste for the Generation of Bioelectricity. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2016, 3, 38. [CrossRef]

[72] Fernando, E.; Keshavarz, T.; Kyazze, G. Enhanced Bio-Decolourisation of Acid Orange 7 by Shewanella Oneidensis through Co-Metabolism in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 72, 1–9. [CrossRef]

[73] Hassan, S.H.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Oh, S.E. Power Generation from Cellulose Using Mixed and Pure Cultures of Cellulose-Degrading Bacteria in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2012, 51, 269–273. [CrossRef]

[74] Palanisamy, G.; Jung, H.Y.; Sadhasivam, T.; Kurkuri, M.D.; Kim, S.C.; Roh, S.H. A Comprehensive Review on Microbial Fuel Cell Technologies: Processes, Utilization, and Advanced Developments in Electrodes and Membranes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 598–621. [CrossRef]

[75] Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Tedersoo, L.; Haelewaters, D.; Rajeshkumar, K.C.; Zhao, R.L.; Aptroot, A.; Leontyev, D.V.; Saxena, R.K.; et al. Outline of Fungi and Fungus-like Taxa. Mycosphere Online J. Fungal Biol. 2020, 11, 1060–1456. [CrossRef]

[76] Vaksmaa, A.; Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Ghosh, P.; Zeghal, E.; Hernando-Morales, V.; Niemann, H. Role of Fungi in Bioremediation of Emerging Pollutants. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1070905. [CrossRef]

[77] Dinakarkumar, Y.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Gujjula, K.R.; Vasu, V.; Balamurugan, P.; Murali, G. Fungal Bioremediation: An Overview of the Mechanisms, Applications and Future Perspectives. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 6, 293–302. [CrossRef]

[78] Chugh, M.; Kumar, L.; Shah, M.P.; Bharadvaja, N. Algal Bioremediation of Heavy Metals: An Insight into Removal Mechanisms, Recovery of by-Products, Challenges, and Future Opportunities. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100129. [CrossRef]

[79] Goswami, R.K.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. Microalgae-Based Biofuel-Integrated Biorefinery Approach as Sustainable Feedstock for Resolving Energy Crisis. In Bioenergy Research: Commercial Opportunities & Challenges; Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, N.; Singh, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021. pp. 267–293. [CrossRef]

[80] Oyetibo, G.O.; Miyauchi, K.; Huang, Y.; Chien, M.F.; Ilori, M.O.; Amund, O.O.; Endo, G. Biotechnological Remedies for the Estuarine Environment Polluted with Heavy Metals and Persistent Organic Pollutants. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 119, 614–625. [CrossRef]

[81] Babu, A.G.; Kim, J.D.; Oh, B.T. Enhancement of Heavy Metal Phytoremediation by Alnus Firma with Endophytic Bacillus Thuringiensis GDB-1. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 250–251, 477–483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[82] Poo, K.M.; Son, E.B.; Chang, J.S.; Ren, X.; Choi, Y.J.; Chae, K.J. Biochars Derived from Wasted Marine Macro-Algae (Saccharina Japonica and Sargassum Fusiforme) and Their Potential for Heavy Metal Removal in Aqueous Solution. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 364–372. [CrossRef]

[83] Goswami, R.K.; Agrawal, K.; Mehariya, S.; Verma, P. Current Perspective on Wastewater Treatment Using Photobioreactor for Tetraselmis Sp.: An Emerging and Foreseeable Sustainable Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61905–61937. [CrossRef]

[84] Li, J.; Liu, R.; Tao, Y.; Li, G. Archaea in Wastewater Treatment: Current Research and Emerging Technology. Archaea 2018, 2018, 6973294. [CrossRef]

[85] Schmidt, I.; Sliekers, O.; Schmid, M.; Bock, E.; Fuerst, J.; Kuenen, J.G.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Strous, M. New Concepts of Microbial Treatment Processes for the Nitrogen Removal in Wastewater. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 481–492. [CrossRef]

[86] Seviour, R.J.; Mino, T.; Onuki, M. The Microbiology of Biological Phosphorus Removal in Activated Sludge Systems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 99–127. [CrossRef]

[87] Jamal, M.T.; Broom, M.; Al-Mur, B.A.; Al Harbi, M.; Ghandourah, M.; Al Otaibi, A.; Haque, M.F. Biofloc Technology: Emerging Microbial Biotechnology for the Improvement of Aquaculture Productivity. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 401–409. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[88] Martins, A.M.P.; Heijnen, J.J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Bulking Sludge in Biological Nutrient Removal Systems. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 86, 125–135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[89] Xing, D.; Zuo, Y.; Cheng, S.; Regan, J.M.; Logan, B.E. Electricity Generation by Rhodopseudomonas Palustris DX-1. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4146–4151. [CrossRef]

[90] Uría, N.; Muñoz Berbel, X.; Sánchez, O.; Muñoz, F.X.; Mas, J. Transient Storage of Electrical Charge in Biofilms of Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1 Growing in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 10250–10256. [CrossRef]

[91] Malvankar, N.S.; Lovley, D.R. Microbial Nanowires: A New Paradigm for Biological Electron Transfer and Bioelectronics. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1039–1046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[92] Tsekouras, G.J.; Deligianni, P.M.; Kanellos, F.D.; Kontargyri, V.T.; Kontaxis, P.A.; Manousakis, N.M.; Elias, C.N. Microbial Fuel Cell for Wastewater Treatment as Power Plant in Smart Grids: Utopia or Reality? Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 843768. [CrossRef]

[93] Deshmukh, R.; Khardenavis, A.A.; Purohit, H.J. Diverse Metabolic Capacities of Fungi for Bioremediation. Indian. J. Microbiol. 2016, 56, 247–264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[94] Abdel-Raouf, N.; Al-Homaidan, A.A.; Ibraheem, I.B.M. Microalgae and Wastewater Treatment. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 19, 257–275. [CrossRef]

[95] Ledin, M. Accumulation of Metals by Microorganisms—Processes and Importance for Soil Systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2000, 51, 1–31. [CrossRef]

[96] Aquino, E.; Barbieri, C.; Oller Nascimento, C.A. Engineering Bacteria for Bioremediation. In Progress in Molecular and Environmental Bioengineering—From Analysis and Modeling to Technology Applications; Carpi, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2011. [CrossRef]

[97] Bayramoğlu, G.; Tuzun, I.; Celik, G.; Yilmaz, M.; Arica, M.Y. Biosorption of Mercury(II), Cadmium(II) and Lead(II) Ions from Aqueous System by Microalgae Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii Immobilized in Alginate Beads. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2006, 81, 35–43. [CrossRef]

[98] Akar, T.; Tunali, S. Biosorption Characteristics of Aspergillus Flavus Biomass for Removal of Pb(II) and Cu(II) Ions from an Aqueous Solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1780–1787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[99] Yergeau, E.; Sanschagrin, S.; Beaumier, D.; Greer, C.W. Metagenomic Analysis of the Bioremediation of Diesel-Contaminated Canadian High Arctic Soils. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30058. [CrossRef]

[100] Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Long, H.; Zhao, X.; Jia, K.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, D. bifA Regulates Biofilm Development of Pseudomonas Putida MnB1 as a Primary Response to H2O2 and Mn2. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1490. [CrossRef]

[101] Vega-Páez, J.D.; Rivas, R.E.; Dussán-Garzón, J. High Efficiency Mercury Sorption by Dead Biomass of Lysinibacillus Sphaericus-New Insights into the Treatment of Contaminated Water. Materials 2019, 12, 1296. [CrossRef]

[102] Sar, P.; Islam, E. Metagenomic Approaches in Microbial Bioremediation of Metals and Radionuclides. In Microorganisms in Environmental Management: Microbes and Environment; Satyanarayana, T.; Johri, B.N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. pp. 525–546. [CrossRef]

[103] Villegas-Plazas, M.; Sanabria, J.; Junca, H. A Composite Taxonomical and Functional Framework of Microbiomes under Acid Mine Drainage Bioremediation Systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109581. [CrossRef]

[104] Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Thirumalesh, B.V.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Tripathi, M. Recent Strategies for Bioremediation of Emerging Pollutants: A Review for a Green and Sustainable Environment. Toxics 2022, 10, 484. [CrossRef]

[105] Jaiswal, S.; Singh, D.K.; Shukla, P. Gene Editing and Systems Biology Tools for Pesticide Bioremediation: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[106] Rodríguez, A.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Sánchez-Salinas, E.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Tovar-Sánchez, E.; Ortiz-Hernández, M.L. Pesticide Bioremediation: OMICs Technologies for Understanding the Processes. In Pesticides Bioremediation; Siddiqui, S.; Meghvansi, M.K.; Chaudhary, K.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. pp. 197–242. [CrossRef]

[107] Sharma, P.; Singh, S.P.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Tong, Y.W. Omics Approaches in Bioremediation of Environmental Contaminants: An Integrated Approach for Environmental Safety and Sustainability. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[108] Tripathi, M.; Singh, D.N.; Vikram, S.; Singh, V.S.; Kumar, S. Metagenomic Approach towards Bioprospection of Novel Biomolecule(s) and Environmental Bioremediation. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2018, 22, 1–12. [CrossRef]

[109] Gaur, V.K.; Gautam, K.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, P.; Dwivedi, S.; Srivastava, J.K.; Varjani, S.; Ngo, H.H.; Kim, S.H.; Chang, J.S.; Bui, X.T.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Sustainable Strategies for Combating Hydrocarbon Pollution: Special Emphasis on Mobil Oil Bioremediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155083. [CrossRef]

[110] Sanghvi, G.; Thanki, A.; Pandey, S.; Singh, N.K. 17—Engineered Bacteria for Bioremediation. In Bioremediation of Pollutants; Pandey, V.C.; Singh, V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. pp. 359–374. [CrossRef]

[111] Dar, P.A.; Yahya, M.Z.A.; Savilov, S.V.; Agrawal, S. Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens Strain NSB4 Bacteria for Treating Wastewater for Fuel Cell Application. Zast. Mater. 2024, 65, 612–622. [CrossRef]

[112] Kalra, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Thakral, N. Bacillus Aryabhattai: A Multi Metal Resistant Sewage Water Bacteria and Bioremediatory Tool for Sewage Water Pollutants. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2024, 28, 329–340. [CrossRef]